Defense lawyers are supposed to do what’s best for a suspect, so what happens when attorney and client don’t even agree on the most basic of things? In this case, whether or not to admit guilt. On Wednesday, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in the case McCoy v. Louisiana.

Robert McCoy‘s petition for writ of certiorari laid it out like this:

Is it unconstitutional for defense counsel to concede an accused’s guilt over the accused’s express objection?

McCoy was convicted in a Louisiana court in 2011 for the shooting deaths of three of his estranged wife’s relatives: her mother Christine Colston-Young, stepfather Willie Young, and her son Greg Colston. Accordingly, he was sentenced to death. The problem was, however, that McCoy didn’t like how his attorney Larry English handled the case.

In a Dec. 4, 2011 statement to a Louisiana court, English said there was too much evidence against his client, and had tried to pursue a plea deal. It was better to admit guilt so as to avoid the death penalty. McCoy rebuffed him, however, and accused English of conspiring with prosecutors and law enforcement, English said.

“I met with Robert at the courthouse and explained to him that I intended to concede that he had killed the three victims in the guilt phase of his trial in an effort to save his life,” English wrote. He later stated, “I explained that I felt that I had an ethical duty to save his life, regardless of what he wanted to do.”

McCoy tried firing English, but the court ruled this attorney-client relationship would continue into the trial.

“I firmly believe that Robert McCoy is insane and was not competent to be tried,” English wrote. His client suffered from a delusion- and paranoia-fueled mental illness, and could not make rational decisions in regard to the evidence at hand, he claimed.

During the opening statement, English told the jury his client was guilty. Really!

“I’m telling you, Mr. McCoy committed these crimes,” he said, according to McCoy’s petition to the U.S. Supreme Court.

McCoy argued this violated his Sixth Amendment rights.

“Mr. McCoy was convicted and sentenced to death after his counsel conceded his guilt over his repeated, timely and express objections,” his petition said.

His legal team also asked the Supreme Court to consider a second question about how the prosecution and defense struck African-Americans on the jury, but justices only granted certiorari on the first question.

In their response to McCoy’s petition, Louisiana prosecutors argued that English’s strategy didn’t violate the defendant’s constitutional rights.

The trial tactic of “admit the act and win the case” by trying to save the defendant’s life in a capital murder trial where evidence of guilt is overwhelming, the crime is heinous and the defendant refuses to cooperate with counsel is aimed at maintaining credibility with the jury in the penalty phase. Counsel’s strategic choices should not be impeded by a rigid blanket rule demanding the defendant’s consent. Counsel’s trial strategy under the circumstances of this case satisfies the Strickland standard because it is not the equivalent to a guilty plea and McCoy still retained the rights accorded a defendant in a criminal trial.

“Strickland standard” is in reference to the 1984 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Strickland v. Washington. In that case, justices took steps in defining how bad a lawyer’s work must be in order to violate a defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to counsel.

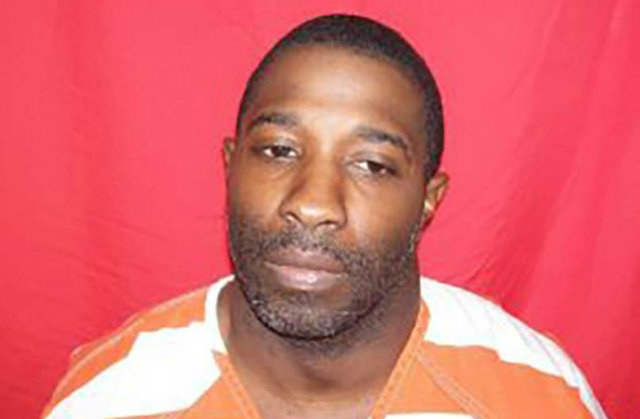

[Mugshot via Bossier Parish Sheriff’s Office]