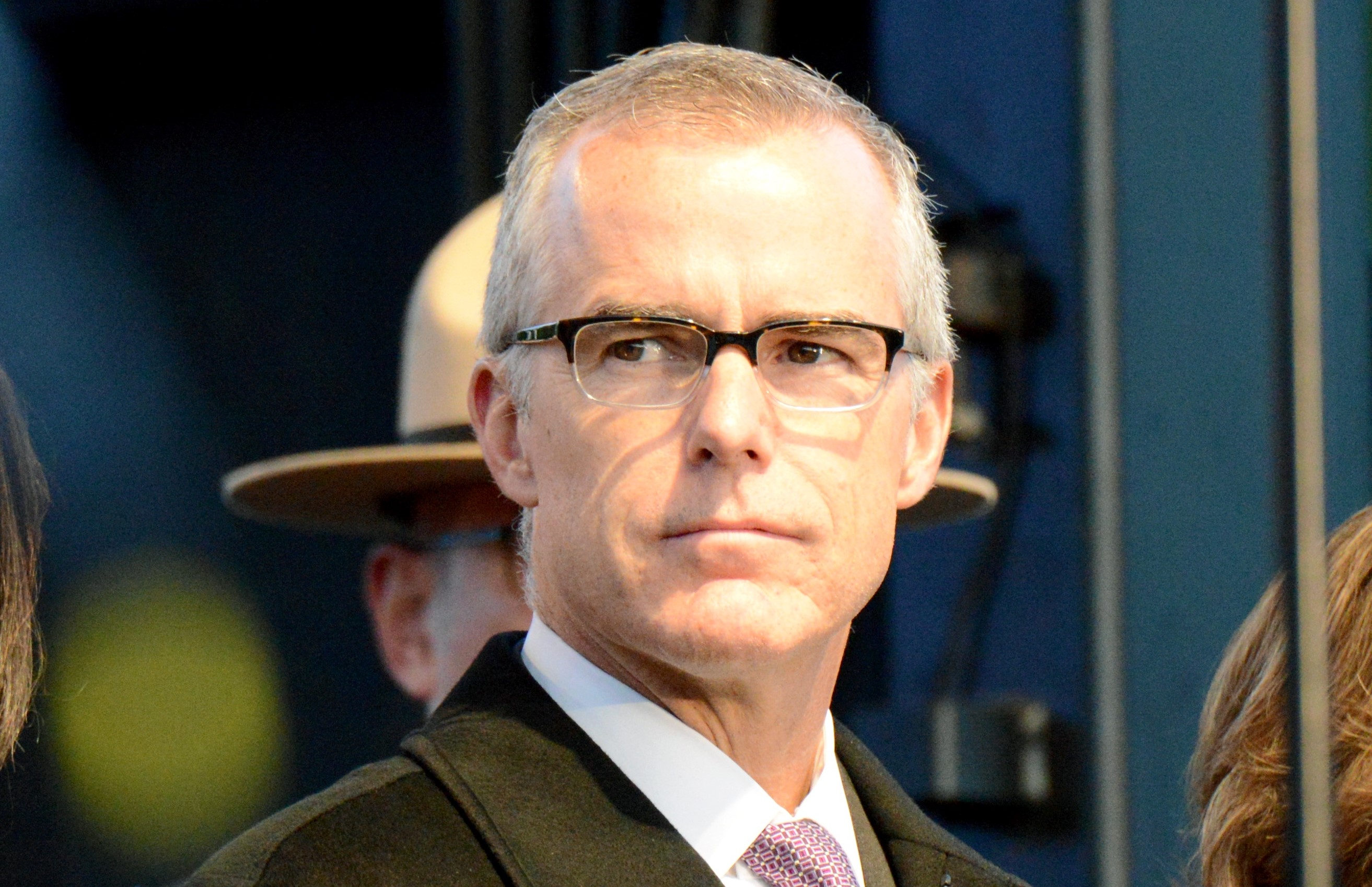

Andrew McCabe has been fired.

At 9:59 p.m. Friday night, Attorney General Jeff Sessions acted on a prior report of the Office of Inspector General (“OIG”)–as well as the recommendation of a career official with the Office of Professional Responsibility (“OPR”)–and ousted the 20-year veteran of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) who had recently gone on extended sick leave to remove himself from the daily law enforcement-like activities of the Donald Trump administration.

Prior to Sessions’ decision, McCabe was widely expected to retire this Sunday, his 50th birthday, to take advantage of the FBI’s minimum retirement age and begin collecting a pension estimated at roughly $55,000 per year. Now, of course, because he was fired, McCabe is no longer entitled to collect this pension any time soon–and likely will not be able to recover the full $1.8 million value.

One anonymous and former FBI agent allegedly told one Daily Beast reporter that McCabe will be able to easily appeal and win because things like this happen all the time. That’s not quite the sort of legal authority we’re inclined to hang our collective hats on here. So, let’s take a deeper dive.

1. “It’s not a question of merit…”

The Merit Systems Protection Board (“MSPB”) is the federal agency which typically deals with claims filed by civil service employees who believe they’ve suffered indignity rising to the level of unlawful retaliation. But, according to the OIG’s own Evaluation and Inspections Division, this avenue is specifically not available for the FBI’s top brass or even FBI agents generally–except for veterans in very specific circumstances.

Tom Devine, who heads the Government Accountability Project noted in an aptly brief summary of the non-applicable law here, “There’s no statutory basis to go to court.”

Essentially, McCabe cannot even access the MSPB’s protections as a basic matter or law. So, that’s out.

2. “Blow the whistle…where you get that from?”

Federal whistleblower protection laws don’t have much to offer McCabe either. Codified at 5 U.S.C. § 2303, those laws offer a vast series of protections for certain whistleblowers who make protected disclosures outlined in the statute.

Here, it appears McCabe made his disclosures “to the news media”–if Sessions’ firing statement is correct. For starters, the FBI’s internal whistleblower protections definitely don’t apply to media leaks. But let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that McCabe’s disclosure(s) could be slotted into one of the eight delineated and protected ways FBI agents are allowed to blow the whistle on lawbreaking and/or corruption.

There’s still at least one snag: Section 2303 has an exception for employees whose jobs are designated as “a confidential, policy-determining, policymaking, or policy-advocating character.” This would almost certainly encapsulate McCabe’s role because the FBI’s deputy director advocates policy and at least has a hand in some aspects of policymaking and policy-determining.

And another snag: Section 2303 also only offers protection in instances where FBI agents are retaliated against by their higher-ups who are also employed by the FBI. This would seemingly preclude the law’s application to McCabe because if there was any cognizable “retaliation” against McCabe, that retaliation came from Jeff Sessions, not another FBI employee. So, this avenue is unavailable to McCabe as well.

3. “When it all, all falls down…”

Since whistleblowing and typical civil service redress options are almost certainly unavailable to McCabe, he could plausibly try to file a complaint via the DOJ’s own internal processes.

For this, McCabe would start with the Office of Attorney Recruitment & Management (the ampersand is part of their digital stationary) and file his initial claim there.

As Eric Columbus, a former Obama administration apparatchik at the Department of Justice, noted, McCabe’s case would then move through the Deputy Attorney General’s (“DAG”) office. But Columbus also noted that McCabe’s recourse via this method is slim to nonexistent.

According to Columbus, McCabe’s theoretical attempt would probably end with the DAG because it’s highly unlikely that office–which operates under the authority of the AG’s office–would find itself capable of cobbling together a finding that Sessions retaliated against McCabe.

Why? Well, aside from the obvious reason that Sessions simply wouldn’t allow it, there’s nothing apparent as to why Sessions would have retaliated against McCabe. According to Sessions’ report (which critics have and will deride as pretext), McCabe was fired for leaking and lying about leaking. If this really happened, then McCabe’s case is shut tighter than Napoleon’s tomb.

Former assistant FBI director Tom Fuentes said, in comments to The Daily Beast, “From the day you become an agent, and I mean the very first minute you’re at Quantico, you are told that lack of candor is the very worst sin you can commit, just short of murder.”

Furthermore, the FBI’s own Office of Professional Responsibility (“OPR”) signed off on McCabe’s firing with their own imprimatur–in fact, the FBI’s OPR recommended McCabe’s dismissal over the alleged leaks and “lack of candor.” Fuentes noted the import of this development:

You have the OPR recommending the firing. That’s not going to be a political decision.

Ultimately, whether or not McCabe’s firing was justified seems to depend entirely on one’s subjective opinion of McCabe’s former boss and current president, Donald Trump. We’ll leave that determination alone.

As for McCabe’s legal recourse? That’s more objectively dealt with. And it doesn’t look there’s much for the recently-fired careerist to work with. He’ll probably be okay, though. Andrew McCabe has an estimated net worth of $11 million.

[Image via the Federal Bureau of Investigation]