There are at least two animals living permanently outside the Albert V. Bryan Courthouse in the Eastern District of Virginia. One is a tortoise–jutting out and looking to the side; one is a hare–illustrated in four panels signifying movement–in bas-relief. Both creatures rest at the feet of Justice and immediately below a raised inscription:

JUSTICE DELAYED

JUSTICE DENIED

The proceedings in the case of the United States v. Paul J. Manafort, Jr. have done these animals and their reconfigured moral well. At least for the most part. But on Monday, the final day of the prosecution’s case against Paul Manafort on charges of bank fraud and tax evasion was largely spent in discussion away from the eyes and ears of the jury–and it took quite awhile.

Most of this legal wrangling had to do with “three questions” and exactly one witness.

After hearing testimony from immunized banker James Brennan, government attorneys, led by Assistant U.S. Attorney Uzo Asonye, wanted to bring Paula Liss back to the stand so that she could testify for a second time–against the wishes of Manafort’s defense counsel, who had moved to bar any further testimony from the prosecution’s witness.

Last week, Liss, who is a senior special agent for the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), testified that Manafort had failed to disclose various foreign bank accounts under his ownership or control. On Monday, the prosecution said they only wanted to ask Liss an additional “three questions” in regards to whether Manafort’s business entities–DMP International and Davis Manafort Partners–had also failed to file such disclosures.

Over the course of multiple public conferences, private bench conferences and concomitant recesses and breaks, Judge T.S. Ellis III pulled out all the stops in order to move things along. That is, Ellis was initially disinclined to allow further testimony from the prosecution and clearly wanted the government to rest their case. But in so doing, proceedings in the so-called “Rocket Docket” ground to a very slow crawl.

The government argued they should be allowed to elicit testimony regarding those aforementioned account disclosures because such testimony spoke to Manafort’s alleged intent when he failed to file individual disclosures for tax years 2011-2014. (Under federal laws and regulations, there are separate disclosure requirements for individuals and businesses when they own foreign bank accounts.)

Judge Ellis was askance, telling Asonye at one point, “[The business entities] are not indicted…you could have indicted them.” At another point, Ellis noted, “This is not like a normal case,” a reference to how criminal defendants are usually very much aware of the laws they are breaking when they break them. The judge went on, “I don’t see what showing these other events shows about his knowledge.”

Asonye’s argument relied on multiple points which were eventually whittled down to the fact that Manafort had received five engagement letters from his longtime accounting firm which spelled out the foreign bank account disclosure requirements.

The defense argued that their client could not be convicted based on the alleged crimes or regulatory mishaps of Manafort’s business entities because those entities were separate parties and therefore any of their alleged actions (or inactions) raised separate and prejudicial legal issues–issues were not covered by, or charged in, Robert Mueller‘s indictment of Manafort.

Ancillary to the defense’s broader point was the fact neatly supplied by Ellis. To wit, that the government could have indicted Manafort’s companies, but simply chose not to do so.

The government responded that Manafort’s defense had basically raised the issue themselves–or were at least preparing to bring it up during closing arguments. The defense shot back that they had not done any such thing and were only going to bring up Manafort’s ownership shares of DMP International for two tax years because the amount he owned during those years would not have triggered the foreign account disclosure requirement.

Ellis attempted to short-circuit the dragged out debate club atmosphere by asking the defense, “Are you gonna ask that?” Before a clear answer was supplied, however, Ellis shifted his focus to the prosecution again, demanding, “What’s the argument you’re afraid of?” Ultimately, neither question was answered directly.

Eventually, and after another quick break, Ellis decided to allow Liss’ testimony. The judge made clear that he would only allow her testimony with a limiting instruction. Asonye then stepped into a flash bang of judicial sarcasm when he noted, “A limiting instruction would be appropriate.” To which Judge Ellis quickly corrected, “Necessary.”

As the jury finally returned to the courtroom, Ellis began, “The bad news is we have one more witness,” before quickly amending his statement and then placing Liss’ testimony in limited context.

That is, Judge Ellis clarified that: (1) Manafort could not be convicted for any crimes not alleged in the indictment; (2) that DMP International and Davis Manafort Partners were not charged in the indictment but could have been; and (3) that the final portion of testimony could only be considered in terms of whether it had any impact on Manafort’s “willfulness” to commit a crime.

Paula Liss took the stand. Those promised “three questions” were quickly doled out and just as quickly answered. Liss testified as to her credentials and then said she searched FinCEN records for foreign bank account disclosure filings. During her searches, Liss said, she found no records of any such filings for DMP International or Davis Manafort Partners during the years in question. And with that, Liss was finished.

There was no cross-examination and the prosecution rested their case. Judge Ellis dryly noted that Liss had actually been asked five questions–to a brief flurry of laughter in the courtroom. In all, the special agent’s testimony had taken less than two minutes.

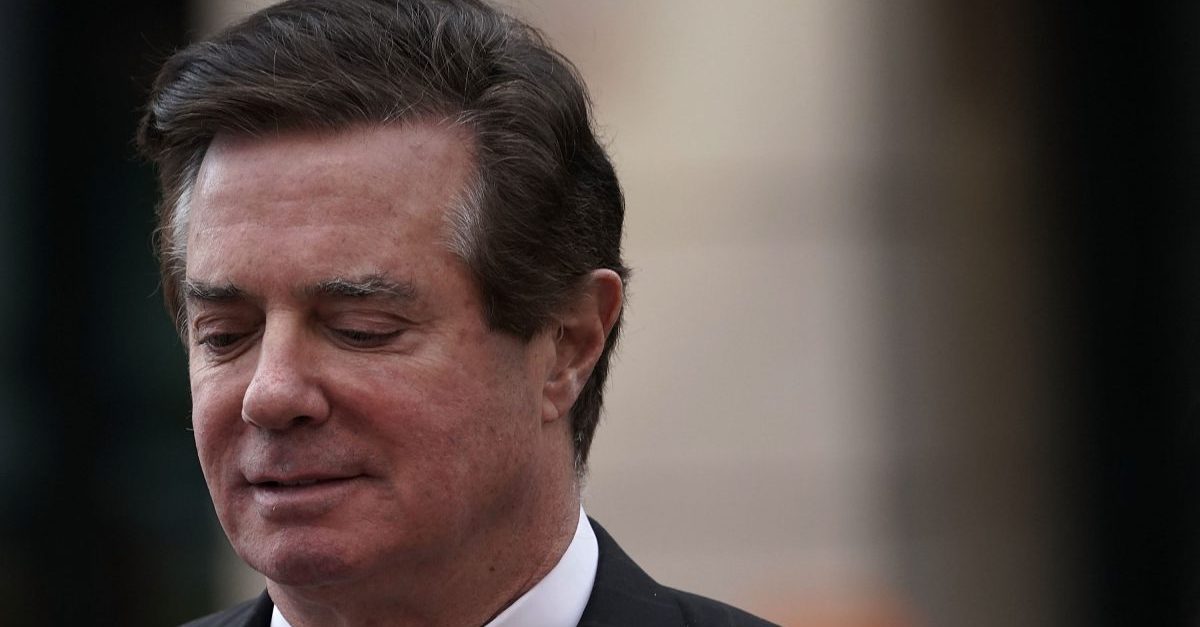

[Image via Alex Wong/Getty Images]