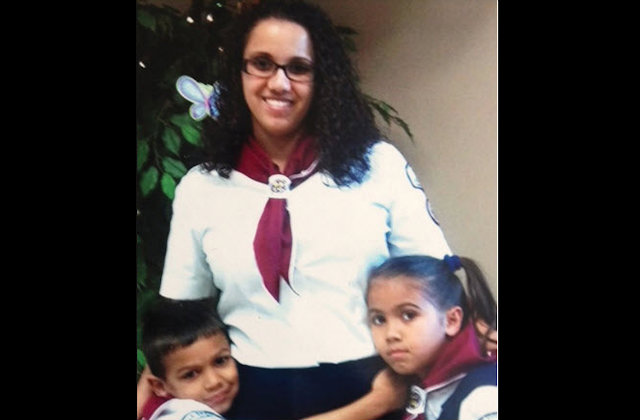

The charges against 35-year-old Luis Toledo of Volusia County, Florida, are heinous. He’s on trial right now on accusations he murdered his wife, Yessenia Suarez, and her two children. Thalia Otto was nine. Michael Otto was eight. Their bodies have never been found. The defense has argued that without evidence of a crime, there cannot be criminal charges against Toledo, the defendant.

The evidence against Toledo is circumstantial, but there is plenty of it. According to testimony, Toledo installed spyware on his wife’s phone to confirm whether she was having an affair. (Her lover later admitted the affair in court.) When Toledo found the evidence he was looking for, he confronted his wife and her lover where they worked together. The date was October 22, 2013. A number of co-workers witnessed the chaos. One called 911. According to Suarez, Toledo slapped her in the face, though no other co-workers witnessed the strike. The co-worker’s 911 call captured the sounds of the fight.

Toledo took off before police arrived. He was not immediately arrested.

Later that night, prosecutors believe things escalated at home. Suarez was last heard from on October 23, 2013. At 1:03 a.m., Suarez called her lover, who later testified Suarez sounded “stressed” and that her speech was “slurred.” Neither she nor her two children were ever seen or heard from again.

A LawNewz.com review of law enforcement records from the October 22nd incident paints a chilling picture of the relationship between Toledo and Suarez. It also raises questions as to why Toledo was not arrested that day. The answer lies in part in the patchwork domestic abuse laws across multiple states and leads to questions about whether stronger laws could have protected victims such as Suarez.

The Workplace Incident

According to law enforcement records, at 1:22 p.m. on October 22nd, local police went to the business where Suarez worked with her lover to respond to the 911 call placed by Suarez’s coworker.

The following facts emerge from a review of police records from that day, including reports from responding officers, interview checklists, and statements from Suarez herself.

On one police form called a Domestic Violence Assessment Referral Inquiry, an officer noted that:

- Toledo told Suarez how he planned to kill her

- Suarez believed Toledo could kill her

- Toledo had strangled Suarez

- Toledo had physically harmed Suarez one to five times

- Toledo had threatened to harm Suarez with a knife

- Toledo had “attempted” to control Suarez’s activities

- Toledo had a history of violence against other partners

- Toledo had held Suarez against her will

- “Jealousy” is what causes Toledo to become violent.

According to other police interview records and checklists which detailed the nature of the relationship, Suarez also told police on October 22nd that Toledo:

- Physically harmed her

- Threatened her with a knife

- Tried to strangle her

- Stalked, followed, or watched her

- Was jealous of her friendships

- Had violent history with other partners

- Had been violent in front of others

- Had been “significantly stressed”

- Had held her against her will

- Had thrown her

- Had mentioned suicide or homicide.

However, on that particular document, Suarez also said Toledo had not been violent of threatening to her children, did not get high or drunk regularly, did not try to control her activities, and did not have access to weapons.

Suarez told the responding officer in a separate sworn statement that she and Toledo were planning to split up. Suarez said that Toledo had found text messages on her phone, became angry, and confronted her outside her workplace. Toledo then went to the building, got buzzed in, and started looking for a manager. Suarez followed him inside. At the end of a hallway, Suarez said Toledo slapped her on the left side of her cheek. The responding officer observed that Suarez’s cheek was red. No other employees saw Toledo strike Suarez and no surveillance cameras recorded the incident, though other employees did hear Suarez yell loudly after the strike.

Suarez further provided police with her own handwritten narrative of what happened. It re-confirms many of the previous facts, but adds that Toledo came to her workplace “with accusations” and that she “begged him to stop acting crazy” before he went inside and ultimately slapped her in the left cheek.

In a series of yet additional written statements and police checklists taken on October 22nd, Suarez indicated that she was “in fear of the defendant” and that she did “not want the defendant to return” to their home. Though she refused to go as far as to say she wanted no contact whatsoever with the defendant, she did say she wanted the defendant to have only non-violent contact with her. She said there were “multiple past incidents of unreported” domestic violence and that she planned to file for an injunction against Toledo. She asked that her whereabouts be kept confidential, that she be notified immediately if Toledo were to be released from jail, and that she would be staying at her mother’s house instead of her primary residence.

The numerous statements became eerie predictions of what prosecutors believe occurred over the next seventeen hours.

The responding officer gave Suarez a date and time to speak with prosecutors: October 25, 2013, at 900 a.m. Suarez never made it. She was also given written information about her legal rights, including a hotline for an emergency shelter. There is no evidence in the documents that Suarez indicated she intended to seek help there.

There is no also identifiable reference to Suarez’s affair in the October 22nd police records beyond it being referenced as “accusations” Toledo made against Suarez.

Toledo wound up speaking with the responding officer by phone. Though the exact nature of the conversation is blacked out of the available report, Toledo argued with the officer about the nature of any possible charges, said the officer had no jurisdiction to arrest him, and hung up on the officer.

The next day, after Suarez disappeared, her mother told police that Suarez came to her house on the afternoon of the 22nd (after the workplace incident). Toledo showed up at about 6:00 p.m. that night to try to patch things up. Toledo left to go home at about 7:00 p.m., the mother told police.

It seems Suarez changed her mind that evening as to whether she wanted to stay away from Toledo. Her mother told police Suarez decided to go home with her children about 45 minutes after Toledo left. Suarez told her mother she was going to try to “make amends” with Toledo, according to the mother’s statement to law enforcement. Suarez’s mother also said Suarez had made a deal with Toledo whereby Toledo could stay in their home until Toledo had the money to move out.

A charging affidavit states that an arrest warrant for Toledo related to the domestic violence incident wasn’t sworn out until October 28th, some five days after prosecutors believe Suarez and her children were murdered. (Defense attorneys unsuccessfully questioned the procedural fairness of why Toledo was arrested and held on the domestic violence charge on October 23rd, one day after the workplace incident, but five days before the official warrant.)

The Law

Different states have different legal standards for police action when it comes to domestic violence. The various laws can be grouped into three broad categories: mandatory arrest states, preferred or pro-arrest states, and discretionary arrest states. Florida is among the latter.

In mandatory arrest states, officers are required to make an arrest when investigating a report of domestic violence, though the various states differ as to when the mandatory arrest requirement kicks in. For instance, Arizona law requires an arrest where a victim has been physically injured or where a weapon is used or displayed during a domestic incident. Colorado simply requires arrest where officers have probable cause to believe domestic violence has occurred. Wisconsin requires an arrest where a domestic abuse crime has occurred and either the officer believes continued abuse is likely, there is evidence of physical injury, or the suspect is the predominant aggressor. Yet other so-called “mandatory arrest” states only require an arrest when a suspect violates a restraining order. At least 26 states and the District of Columbia have some form for a mandatory arrest law in domestic violence situations.

In preferred or pro-arrest arrest states, laws encourage, but do not require, officers to make arrests in domestic violence situations. At least six states fall into this category.

In discretionary arrest states, state laws simply say an officer “may” arrest a suspect in a domestic violence situation. At least 40 states have some form of a discretionary arrest statute on the books.

Why don’t all of the above numbers add up to fifty states? A number of states, such as California, have a blend of mandatory arrest, pro-arrest, and officer discretion statutes depending on the type and severity of the alleged harm.

In Florida, where Luis Toledo is accused of killing Yessenia Suarez, the law states that an officer “may” arrest a domestic violence suspect “whenever the officer determines upon probable cause that an act of domestic violence has been committed.” State law also “strongly discourages” mutual arrests and requires officers to make a policy determination as to the primary aggressor.

It’s strongly arguable that a mandatory arrest law in Florida might have saved Suarez’s life. Had officers arrested Toledo on October 22, 2013, after the early afternoon workplace incident, Toledo would not have been in a position to kill Suarez in the early morning hours of October 23, as prosecutors believe happened.

Mandatory arrest laws are not without critics. Some argue they force arrests even after it’s clear things have settled down, where things never escalated to the point of logical police intervention in the first place, or where a complainant wants an officer to act as a peacemaker, not an incarcerator. Some might argue that some mandatory arrest laws are unduly harsh for minor disputes and that a forced arrest could further aggravate a perpetrator, ultimately placing a victim in greater harm if, and when, a suspect is ultimately released.

The Murder Trial

According to a charging affidavit, Toledo initially told police he was sleeping in the parking lot outside his shared home with Suarez rom 11:00 p.m. on October 22nd to 8:00 a.m. on October 23rd. He claimed his wife’s car was gone when he woke up. His own friends contradicted his statement. Toledo showed up at his brother’s house at around 5:00 a.m. to talk about his troubled marriage. Toledo’s own brother said the visit was unannounced and that Toledo appeared “out of it.” Toledo’s neighbor told police Toledo had asked him for help at 6:11 a.m. in what ultimately became an alleged attempt to ditch Suarez’s car in a parking lot one county away. The neighbor saw Toledo wipe the car down with cleaning solution. Later, Toledo told the neighbor that he had “snapped.” The neighbor also watched Toledo throw some of the children’s belongings in a trash bin. The neighbor alerted police when they showed up shortly later that something was fishy about the request to help move the car.

Investigators later found the Thalia Otto’s blood on Toledo’s boots, in Toledo’s master bedroom, and on the trunk mat of Suarez’s car.

After initially claiming he was asleep, Toledo later told investigators he killed his wife by hitting her in the throat and watched her die while she looked at him and gasped for breath. He claimed she grabbed him by the throat first. He claimed during the same interrogation that the neighbor who told police about the attempt to ditch the car was the one who had really killed the two children.

A Florida jury is considering whether Toledo is guilty of first-degree murder related to the presumed deaths of the children and of second-degree murder related to the presumed death of his wife. The first-degree murder charges related to the children carry a possible death sentence. Toledo is also accused of tampering with physical evidence for wiping down his wife’s car and their home.

Aaron Keller is an attorney and a live streaming trial host for the LawNewz Network. Follow him on Twitter: @AKellerLawNewz.