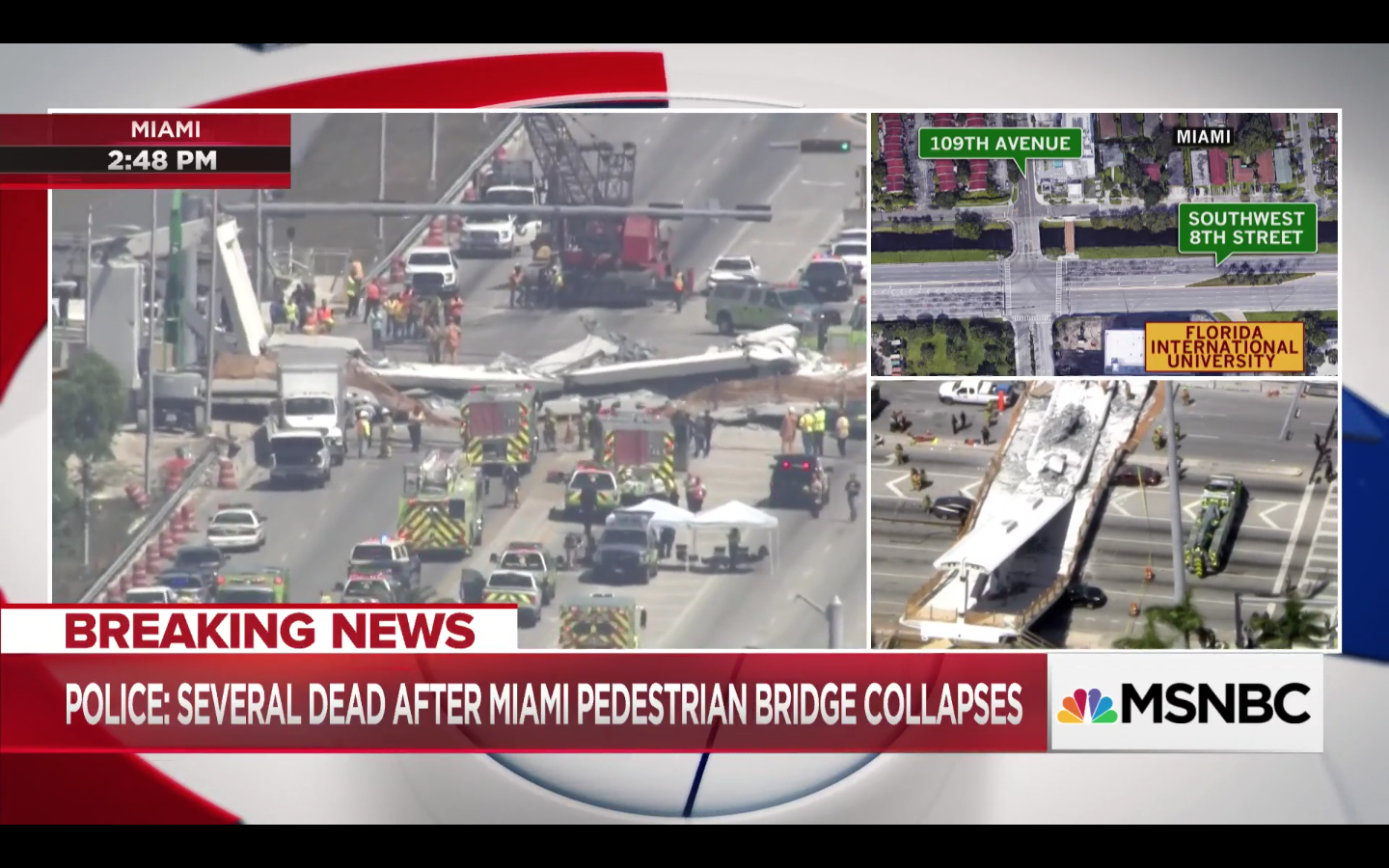

On Thursday, a 950-ton pedestrian walkway collapsed in Miami.

But it may be difficult for victims and their families to hold anyone accountable because laws in The Sunshine State heavily favor business and don’t look too kindly on liability lawsuits.

Several people died as a result of the accident which occurred over a seven-lane stretch of highway adjacent to the campus of Florida International University (“FIU”). Miami-Dade County Fire and Rescue confirmed that multiple people were crushed to death, including pedestrians on the bridge and travelers in cars below.

The bridge itself was designed to withstand hurricane-force wind and was officially known as the “FIU-Sweetwater pedestrian bridge.” This walkway, not yet public, was slated to open in early 2018.

With multiple deaths, injuries and property losses confirmed, public outcry and media coverage will soon shift to possible legal consequences for parties at fault. So, who’s liable for damages when a bridge collapses?

The short answer: in theory, pretty much everyone involved at every level.

The long answer–due to the particularities of Florida law and politics–is a bit more complicated than that.

Law&Crime spoke with prominent personal injury attorney David Eisbrouch for some insight on the basic contours of the likely litigation to come. Eisbrouch stressed that criminal liability was probably not on the table. He said, “Absent any wrongdoing by city officials related to the permits granted for the project, it’s unlikely that any criminal indictments will be issued as a result of the collapse. However it’s too premature to definitely say at this time.”

But that calculus shifts hard, fast and all-but definitively when it comes to civil liability. Eisrbouch noted:

There are myriad possible defendants. This would be a civil lawsuit against multiple parties, brought for the negligent construction of the bridge. The responsible parties could range from the builder, engineer, architect, city, state and any other parties who were contracted to work on that bridge. At this time, it’s too premature to determine the cause of the collapse, but once this occurs it would be easier to identify the culpable parties.

While it’s certainly too early–and the case here is too fact-intensive to say anything for sure–a helpful example immediately arises in the case of Minnesota’s experience under similar circumstances.

On August 3, 2007, the I-35 bridge collapsed in Minneapolis, Minnesota—sending tons of steel and concrete tumbling some 1900 feet into the Mississippi River below. Almost 150 people were injured and 13 died as a result.

Public outcry was swift and lawsuits followed soon thereafter. The justifiably incandescent anger was undergirded by the fact that the U.S. Department of Transportation under George W. Bush deemed the I-35 bridge “structurally deficient” two full years prior to its collapse. The Bush administration quickly cleared itself of any wrongdoing and publicly foisted responsibility onto the State of Minnesota–which ultimately did bear the brunt of litigation brought by victims and their families.

Liability was extensive. Parties subject to liability over the I-35 collapse included the State of Minnesota, the company that designed the bridge, the contractor who built it, the state agencies responsible for inspections and maintenance, and private companies contracted out to perform bridge maintenance.

The legal foundation for all such claims was the basic concept of negligence, which is enshrined in U.S. common law and state tort statutes. Specifically, the parties were ultimately deemed liable if they had a duty to maintain the bridge’s safety and if their failure to do so was found to be a cause of the bridge’s collapse.

Ultimately, victims were awarded $8.9 million in a complex settlement agreement between victims and their families, the State of Minnesota, and engineering and construction firms who worked on the I-35 bridge.

Though the I-35 bridge case’s use as an analogy is somewhat limited due to slightly different facts, the Minnesota example is likely instructive for the present analysis.

To begin with, Florida and Minnesota are vastly different states. In response to the tragedy, Minnesota lawmakers passed legislation providing for a victim’s fund. Don’t expect Florida to follow suit.

And, while one Minnesota state law did limit the state’s own liability, The North Star State is not particularly keen on the sort of “tort reform” which limits liability for the sort of private contractors who work on public bridges viz. engineering, construction or maintenance. Florida law does exactly that.

Florida Statute 337.195(2) reads, in relevant part:

A contractor who constructs, maintains, or repairs a highway, road, street, bridge, or other transportation facility for the Department of Transportation is not liable to a claimant for personal injury, property damage, or death arising from the performance of the construction, maintenance, or repair if, at the time of the personal injury, property damage, or death, the contractor was in compliance with contract documents material to the condition that was the proximate cause of the personal injury, property damage, or death.

This means the companies which built and designed the bridge, Munilla Construction Management and FIGG Bridge Engineers, simply have to show they were in compliance with the terms of their contracts to avoid the worst of the litigation likely headed their way.

The next section of the statute makes clear when the above safe-harbor provision are not effective: “When the proximate cause of the personal injury, property damage, or death is a latent condition, defect, error, or omission that was created by the contractor.” In other words, if an investigation shows either company was not in compliance with said contracts and/or caused a design failure completely beyond the realms of what the contract anticipated, then the safe-harbor terms are not supposed to–and are not likely–to offer much protection for the contractors involved.

Still, another section of the same statute offers even more potential protection for the contractors here. Section 337.195(3) creates a strong presumption in favor of contractors which assumes such contractors designed their plans in line with common industry practices and “with due regard for acceptable engineering standards and principles” simply by virtue of their contract with Florida’s Department of Transportation. This presumption can only be overcome by a showing of gross negligence–which is a difficult legal standard to meet.

Another issue which certainly stands to complicate any legal analysis is the reported presence of pedestrians on an unfinished bridge. David Eisbrouch offered some insight here as well, “Why were people on the bridge if it wasn’t scheduled to open until next year? Who was permitted access? Were they workers or someone else? These are important questions to ask and have answered.”

TL;DR–under basic legal theory and accepted liability law, lots of people have a lot to answer for over this tragic collapse. But do to the anti-tort niceties of Florida law, some potentially responsible parties might find themselves protected from litigation. But until we know a bit more, it’s too soon to say too much for sure.

[image via screengrab/MSNBC]