Dozens of local news anchors reciting the same ominous script about “false news” and “fake stories.” A collective gut check in news rooms across the country. The obvious hint of propaganda as the compiled footage chases down an appropriate analogue.

Welcome to the media landscape gifted to America by the presidency of Bill Clinton.

On June 15, 1995, 81 Senators from both parties voted to advance the Telecommunications Act of 1996. On October 12, 1995, the House of Representatives moved the bill forward without objection as a perfunctory measure. The conference committee report–the final bill–was passed by the House on February 1, 1996. The final House vote: 414 in favor to 16 against–the opposition led by Independent Rep. Bernie Sanders.

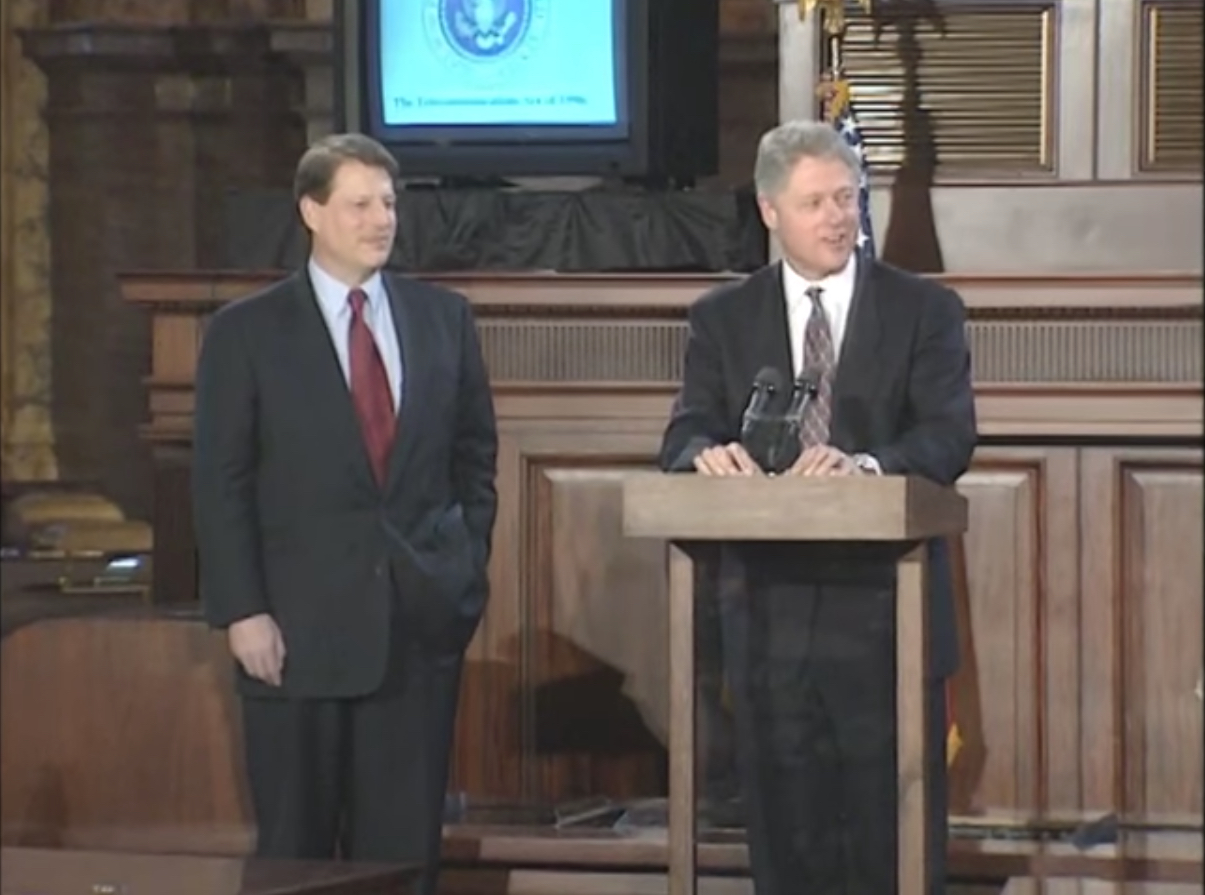

The final Senate vote was equally lopsided: 91 in favor to 5 against. The only remaining opposition in the Senate was four progressive Democrats and a much earlier version of John McCain. With no small amount of fanfare and attention, President Clinton signed the bill into law on February 8, 1996 and one of the New Deal’s longest lasting regulatory frameworks was finally laid to rest.

Clinton and his political allies–like then-Senator Larry Pressler, who authored the bill–hailed the bill’s passage as the harbinger of a new and competitive media landscape with promises of increased options and lower rates for consumers. But not everyone was quite convinced. As Manfred B. Steger and Ravi K. Roy note in Neoliberalism: A Very Short Introduction:

[V]arious consumer groups – and even conservative economists – argued that the overall effects of the Telecommunications Act would result in steep increases in service fees and a marked tendency toward the formation of local and regional corporate monopolies.

Turns out the critics were right. While there is certainly a nearly paralyzing array of options for consumers, those options come from fewer and fewer companies. Meanwhile, the real price of telecommunications services–as with most services in the United States–has steadily increased over time and monopolies are now the order of the day.

But what did the law actually do? Title II did most of the heavy lifting viz. consolidation and the creation of our present day monopoly-centric culture. Section 202 lifted the cap on radio station ownership. Under the previous regulatory regime, a single corporation was limited to owning 40 radio stations. Now, Clear Channel owns in excess of 1,200 radio stations.

Section 202 also increased the number of local television stations that a single corporation could own. Before re-regulation that number was capped at 12. Sinclair Broadcasting Group now owns nearly 250 local television stations. This section also increased the limits on audience reach. Previously, companies were limited to reaching 25 percent of U.S. households. And this landscape is ever-and-still-shifting in the favor of increased media ownership.

An obscure subsection–202(h)–was inserted at the behest of lobbyists for Rupert Murdoch‘s News Corp. This subsection reads:

Further Commission Review: The Commission shall review its rules adopted pursuant to this section and all of its ownership rules biennially as part of its regulatory reform review under section 11 of the Communications Act of 1934 and shall determine whether any of such rules are necessary in the public interest as the result of competition. The Commission shall repeal or modify any regulation it determines to be no longer in the public interest.

The Clinton administration was clueless. They considered this language an innocuous reporting requirement. Since the law passed, however, and after a series of expertly-timed-and-crafted court challenges (the first was initiated by Fox Television), this section has been used to further erode and rescind previous limits on broadcasters. Instead of a reporting requirement, Section 202(h) is consistently used to slash media ownership rules.

Additionally, Title III of the Telecommunications Act removed and reduced Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulations on cross ownership of media entities by cable broadcasters. There are and were other valid concerns and criticisms made about the law–and most, if not all of those prior criticisms are still functioning critiques because the critics back then were mostly on point.

The most apt criticism has been borne out repeatedly. What was previously unthinkable became the new normal: massive corporations bought up dozens, then hundreds, then thousands of media outlets across the country. The idea of media diversity–promised by the law’s boosters–is now laughably quaint.

A 2005 report from public interest watchdog Common Cause noted, “In many ways, the Telecom Act failed to serve the public and did not deliver on its promise of more competition, more diversity, lower prices, more jobs and a booming economy. Instead, the public got more media concentration, less diversity, and higher prices.”

Now, over 90 percent of the country’s media is owned by six or seven corporations.

Sinclair Broadcast Group is actually one of the smaller corporations in this grouping while still managing to achieve the following three amazing feats: (1) Sinclair is the largest television station operator in the country by number of stations (233 when all currently proposed purchases are approved); (2) the largest operator by total coverage (reaching over 40% of American households); and (3) the station operator in the most media markets (over 100).

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 was one of the most important and impactful laws passed in the 20th century. The lite dystopian feel of dozens of voices reading from the same noxious script is what your senators and congresspeople signed up for when they added their voices to the restructuring of the nation’s legal regime as it concerns media–and it’s exactly what Bill Clinton gleefully signed with his own hand (using the same pen President Dwight Eisenhower used to sign the Interstate Highway Act).

[image via screengrab/Clinton Presidential Library]