Stormy Daniels, through her attorney Michael Avenatti, filed a response on Monday to President Donald Trump‘s motion to dismiss her defamation case against him. The filing attacked Trump’s motion from all sides, claiming that not only should it lose due to weak arguments, but because Trump’s lawyer Charles Harder didn’t file it at the right time, or even make the right kind of motion. The case is centered on Trump’s tweet where he called Daniels’ claims regarding an alleged threat someone made to her in 2011 a “con job” about “a nonexistent man.” The threat was allegedly made so she would keep quiet about allegations of an affair she had with Trump.

A sketch years later about a nonexistent man. A total con job, playing the Fake News Media for Fools (but they know it)! https://t.co/9Is7mHBFda

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 18, 2018

Avenatti started off his filing by saying that Trump’s motion (which was titled a “motion to dismiss/strike”) should be really be considered a motion for summary judgment under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. This is because the motion made an argument that Daniels’ claim should be barred under the Texas Citizens’ Participation Act (TCPA), which deals with lawsuits against speech that is of public concern (Harder argued that Texas law should apply because that’s where Daniels was living at the time). Avenatti cites federal case law regarding a similar statute in California, which says that in federal court, motions to strike under the statute on the basis of a lack of proof are to be treated like summary judgment motions.

Avenatti argues that this is relevant because it means the court should not decide on the motion until Daniels has the opportunity to demand and review discovery materials in the case, specifically related to Trump’s knowledge–or lack thereof–regarding the alleged threat. This could include a deposition, something Avenatti has long desired in Daniels’ original case against Trump and Michael Cohen over her hush agreement.

If Avenatti loses that argument, and the court deems Trump’s motion to be a regular motion to dismiss under the TCPA, that could be even worse for Trump’s case, Avenatti argues. The court filing states that under the TCPA, a defendant has 60 days from the time they’re served with a complaint to file a motion to dismiss. In this case, Trump waived service on May 23, 2018, so Avenatti says the clock started ticking then. Therefore, he claims, Trump had until July 23 to file his motion. He states that Trump didn’t file his motion until August 27, it should be denied for being untimely. On top of that, Avenatti claims, a motion to dismiss is decided on the face of the complaint, and therefore Harder’s inclusion of exhibits and a declaration with his motion would be improper.

Ironically, in addition to arguing that Trump’s motion was filed too late as far as the TCPA (which was just part of Harder’s arguments), Avenatti also claims it was filed too early. In a footnote, Avenatti pointed out that Harder ignored local court rules by failing to wait seven days after the two sides had a “meet and confer discussion.” The two sides apparently got together on August 24, which was only three days before Harder filed the motion on Trump’s behalf. Avenatti noted that Judge S. James Otero has been a stickler for following the rules of his court (this is true, as Judge Otero has warned both sides in the hush agreement case).

Before delving into the substance of Stormy Daniels’ case and why it should be allowed to move forward, Avenatti did repeat one questionable argument that he has made in the past. While he made arguments for why Daniels’ case should survive under Texas law, Avenatti claimed that New York law–which is far more favorable to Daniels–should apply, because Trump is a New York resident. Of course, this ignores the fact that Trump was already president when he posted the tweet at the heart of this lawsuit, and was living in the White House.

Procedural issues aside, Harder argued in his August 27 motion that Daniels failed to make out a defamation case because she didn’t illustrate any damage that she allegedly suffered. Avenatti claims that Daniels doesn’t have to prove damage because Trump’s statement was defamation per se, according to the doctrine that certain types of false statements are automatically deemed to be harmful.

Specifically, Avenatti states that Trump accused Daniels of a committing the crime of falsely accusing someone of threatening her. Of course, as Law&Crime noted when Avenatti previously made this claim, the whole purpose of the sketch was to identify who the person behind the alleged threat was. Therefore, Daniels could not have accused any particular individual of threatening her.

Avenatti did make a separate argument for defamation per se, that has more teeth to it. If the judge determines that the case should be decided under Texas law as Harder argues, that state’s law would help Daniels because the statute there says that “written or printed words which charge dishonesty of fraud” are defamation per se. By accusing Daniels of carrying out a “con job,” Trump appears to have satisfied that.

Even if she does have to demonstrate damage, Daniels claims she has done so, in the form of “threats of violence, economic harm, and reputational damage,” resulting in “emotional distress and mental anguish.”

Of course, damage only means something if the statement was indeed false, and even if it’s false, there has to be “actual malice” for statements about public figures. That means Trump would have had to either know the statement was false, or acted with a reckless disregard for whether it was true.

To that end, Avenatti highlights the fact that Trump himself has not made any statement on the matter to dispute Daniels’ claim that he was at fault (emphasis in original):

Mr. Trump submits no declaration of his own or any evidence to establish that he did not act with the requisite fault. This is fatal to his position.

Law&Crime reached out to Harder for comment on Avenatti’s attack on his motion, but Harder has not responded.

Avenatti simply told Law&Crime that he is “confident the motion will be denied.”

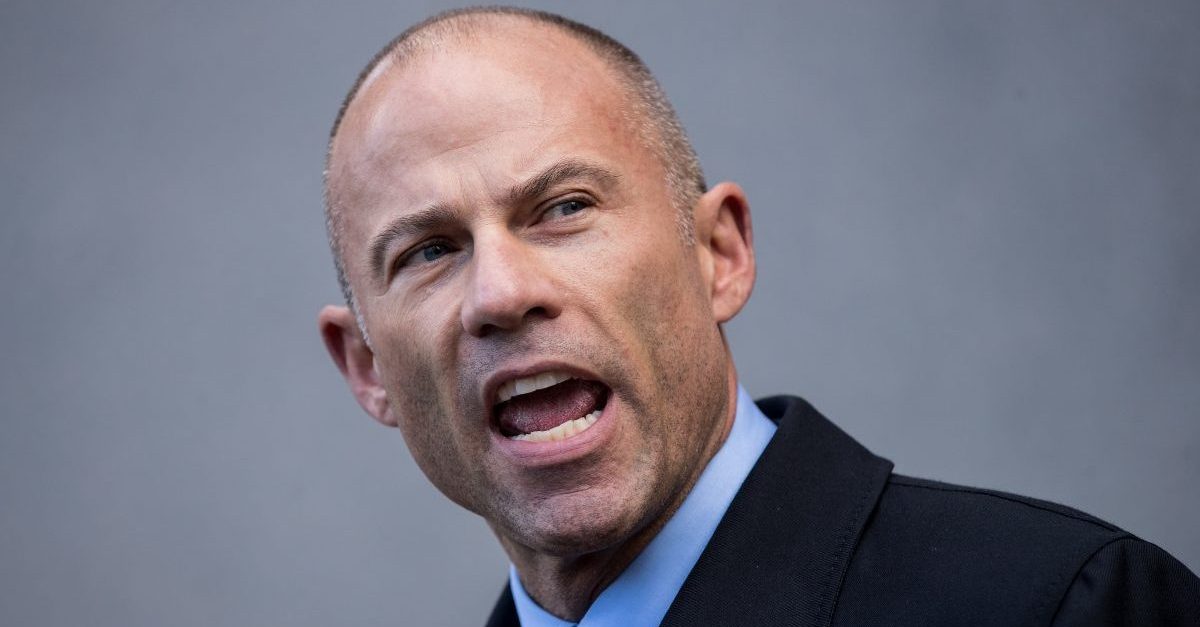

[Image via Drew Angerer/Getty Images]