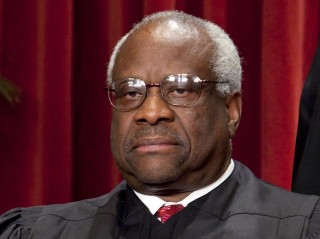

Justice Thomas is at it again. This time, in Utah v. Strieff, Thomas clarifies that the majority of SCOTUS is far more interested in making sure no criminal slips through the cracks than it is in Constitutional liberties. If only those rumors about Thomas’ retirement were true. Sigh.

Justice Thomas is at it again. This time, in Utah v. Strieff, Thomas clarifies that the majority of SCOTUS is far more interested in making sure no criminal slips through the cracks than it is in Constitutional liberties. If only those rumors about Thomas’ retirement were true. Sigh.

A quick recap on the facts:

Douglas Fackrell is a cop who was investigating a drug house. Officer Fackrell saw Edward Strieff coming out of the house, and thought Strieff looked shady. Fackrell knew he didn’t have any legal reason to stop Strieff, so he just asked him for some information about the house. And by “just asked him for some information,” I mean that the cop demanded the guy’s identification, detained him, and called the police dispatcher to see if the Strieff was a criminal.

And guess what? Strieff had an open arrest warrant for a traffic violation! Fackrell then arrested Strieff; as part of the arrest, Fackrell searched him and found some drugs. There’s no question that the stop of Strieff was illegal and unconstitutional. But usually, when evidence is found as a result of an unconstitutional move by the cops, that evidence is excluded under the Fourth Amendment’s exclusionary rule and the related “Fruit of the Poisonous Tree Doctrine.”

Writing for the majority, Justice Thomas does his level best to squeeze the round facts of Strieff into the square hole of the “attenuation doctrine” – an exception to the exclusionary rule. The resulting decision is classic Thomas: he sounds like he’s following the actual law, but he’s actually creating ad hoc rules that reward good police instincts and bad police procedure.

Here’s the basic concept of the attenuation doctrine:

When there’s too distant a relationship between a Constitutional violation by police and the finding of evidence, that evidence isn’t protected by the exclusionary rule. So, for example, if a cop barged into someone’s house without a warrant and grabbed drugs from a drug dealer’s kitchen counter, those drugs would be inadmissible, because they were obtained during an illegal search. But, if a week later, after the smoke cleared and the dust settled, the drug dealer drove over to the police station and confessed that the drugs had been his, then the drugs would be admissible. The dealer’s confession is a sufficiently intervening event that would break the causal chain between the illegal search and the finding of evidence. Once that chain is broken, the illegality is too attenuated to justify suppressing the evidence.

The concept of breaking the causal chain is one that comes up in several areas of law, and has long been a chief culprit in destroying the GPAs of otherwise promising law students. Without going into a dissertation on proximate cause, allow me to characterize the general idea. The chain of causation is strong, and is usually only broken by some unforeseeable intentional act of a third party, an act of God, or some sort of freak accident. We can recognize these “sufficiently intervening causes” because the result in something completely unexpected. Go back to my example above: the drug dealer’s voluntary confession is an unexpected, intentional act — and that’s why it breaks the chain of causation.

In Strieff, the officer’s finding an outstanding warrant is hardly the kind of sufficiently intervening event that would justify throwing the exclusionary rule out the window. The cop questioned Strieff because he expected to find some dirt on him. That’s why he did it. Good police work, for sure. But an unexpected, unforeseeable, intervening cause? No way.

Sure, it’s uncomfortable to side with a criminal defendant when he has clearly broken the law. But if we’re unwilling to do so, then all criminal procedure rules are hopeless. As Justice Sotomayor remarked in her dissent, “it is tempting in a case like this, where illegal conduct by an officer uncovers illegal conduct by a civilian, to forgive the officer. After all, his instincts, although unconstitutional, were correct. But a basic principle lies at the heart of the Fourth Amendment: Two wrongs don’t make a right.”

How is it possible SCOTUS got this wrong?

Well, the justices didn’t really get it wrong as much as they just picked a different analysis that they liked better. Instead of focusing on the purpose of attenuation and the kind of situation it was meant to affect, SCOTUS does a little dance of “it’s not me, it’s you” and defers to a “test” invented by Brown v. Illinois. That was kind of weird, because the Brown case specifically says that it doesn’t create a test. Also, the issue of attenuation has come before SCOTUS since Brown, and the Court has never used this “test.” Justice Thomas’ decision was almost convincing in its confident “what do you mean? We’ve always done it this way.” Except it hasn’t always been done this way. In fact, it’s never done it this way.

The Court often grabs onto three-prong tests as judicial life-preservers when it needs justification to for the outcome it seeks. But what’s disturbing here is that Thomas isn’t doing the legal acrobatics to create better justice, but rather, to empower bad police practices. Justice Sotomayor was right when she warned: “unlawful stops have severe consequences much greater than the inconvenience suggested by the name. This Court has given officers an array of instruments to probe and examine you. When we condone officers’ use of these devices without adequate cause, we give them reason to target pedestrians in an arbitrary manner. We also risk treating members of our communities as second-class citizens. Although many Americans have been stopped for speeding or jaywalking, few may realize how degrading a stop can be when the officer is looking for more. This Court has allowed an officer to stop you for whatever reason he wants—so long as he can point to a pretextual justification after the fact.”

And Sonia knows what is going to happen as a result of this decision. The result will hurt us as a society, but will (of course) affect people of color most of all:

“The white defendant in this case shows that anyone’s dignity can be violated in this manner. But it is no secret that people of color are disproportionate victims of this type of scrutiny.” The Court’s decision isn’t bad because of its obvious disproportionate effect – it’s bad because it erodes an important tenet of criminal procedure. The disparate impact it will have on the poor and minorities is simply another reason why it’s especially distasteful in 2016 America.