ABA Legal Fact Check debuted in August and is the first fact check website focusing exclusively on legal matters. This article has been republished with permission.

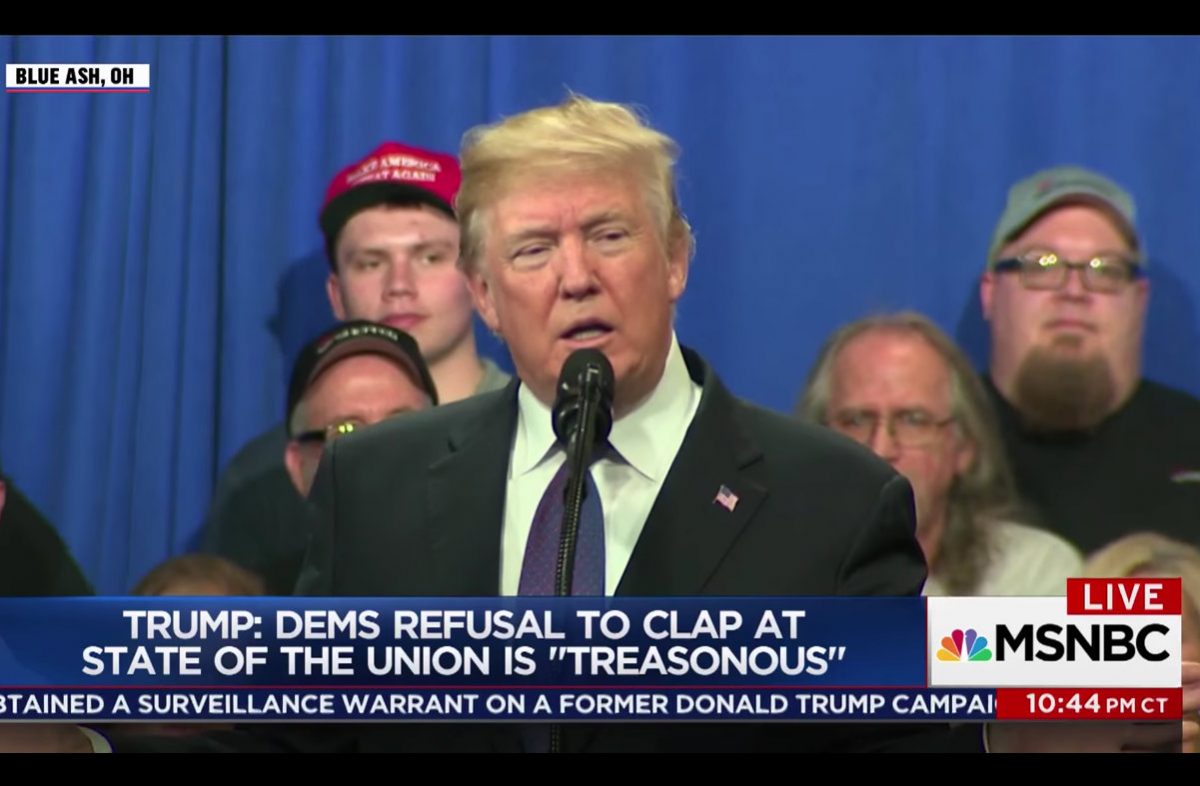

After many Democrats sat stone-faced during his State of the Union address, President Donald Trump remarked: “Can we call that treason? Why not? I mean, they certainly didn’t seem to love our country very much.” For some months, a number of Democrats and others have also used the word treason in reference to a meeting between Trump’s son Donald Jr. and a Russian lawyer: “… (W)e’re now beyond obstruction of justice in terms of what’s being investigated. This is moving into perjury, false statements and even potentially treason,” U.S. Sen. Tim Kaine said last summer. Their assessments raise the question: What constitutes a criminal charge of treason?

While “treason” is often used in lay terms as a synonym for disloyalty, as a legal matter it has a very specific meaning under Article 3, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution. Treason is the betrayal of the U.S. by waging war against it or by consciously acting to aid its enemies. It can only be invoked, as a criminal charge, against an individual with ties to the U.S., in a time of war and when at least two witnesses can testify to an “overt act.”

The founding fathers at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 deliberately tailored a narrow definition of treason as a criminal charge, both specifically rejecting the ability of Congress to define treason and setting a high burden of proof. Historians say the framers did so because they recognized that the broad definition of treason in English common law had allowed it to be used as a political instrument. The charge of treason is the only criminal offense addressed in the Constitution.

John Marshall, who later became the country’s first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, summed up the founding fathers’ concern when he said, “Every member of that Convention — every officer and soldier of the Revolution from (George) Washington down to private, every man or woman who had given succor or supplies to a member of the patriot army, everybody who had advocated American independence — could have been prosecuted and convicted as ‘traitors’ under the British law of constructive treason.”

The First Congress used its constitutional power to establish the punishment for treason – from a minimum sentence of seven years to a maximum sentence of death. Subsequently, Congress modified its penalties, with a conviction now carrying a maximum of death and minimums of five years in jail and a $10,000 fine.

Since 1789, there have only been about 30 treason trials in the U.S. The most famous — considered the trial of the century at the time — involved Aaron Burr in 1807, and it tested the Constitution’s limit on treason. President Thomas Jefferson is said to have pressed for treason charges against Burr, a political opponent, for allegations that he was engaged in a somewhat hazy plot to get the western territories (at that time, Alabama, Mississippi and some of the Louisiana Territory) to leave the U.S., possibly in cahoots with foreign powers. After a trial presided over by Marshall, a jury acquitted Burr.

Because of the limiting language of Article III, disloyal acts in peacetime often result in charges other than treason. Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, for instance, were charged under the Espionage Act for passing along nuclear weapon designs to the then Soviet Union. While the acts occurred during the Cold War, technically the U.S. was at peace with the Soviets. The Rosenbergs were found guilty in 1951 of espionage conspiracy and eventually executed.

Cases of treason have rarely reached the U.S. Supreme Court. Carlisle v. United States in 1872 established the legal basis that noncitizens living in the U.S. are bound to obey all the laws of the country not immediately relating to citizenship, including the law governing treason.

More than 70 years later, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the narrow legal interpretation of treason in Cramer v. United States. The 5-4 decision involved a German-born, naturalized U.S. citizen who had been seen by two FBI agents while in the presence of two suspected German saboteurs who entered the U.S. by submarine during World War II. The naturalized citizen, Anthony Cramer, was found guilty at trial though the FBI agents, who had the pair under surveillance, could not assert what was said at the meetings. In 1945, the Supreme Court rejected the government’s contention that a “little imagination” would suggest what they talked about. It ruled that the evidence was “insufficient to support a finding that the accused had given aid and comfort to the enemy.”

“A citizen intellectually or emotionally may favor the enemy and harbor sympathies or convictions disloyal to this country’s policy or interest, but, so long as he commits no act of aid and comfort to the enemy, there is no treason,” Justice Robert Jackson said in his majority opinion. “On the other hand, a citizen may take actions which do aid and comfort the enemy — making a speech critical of the government or opposing its measures, profiteering, striking in defense plants or essential work, and the hundred other things which impair our cohesion and diminish our strength — but if there is no adherence to the enemy in this, if there is no intent to betray, there is no treason.”

Read more of ABA’s Legal Fact Check series here.

[Screengrab via MSNBC]