The Supreme Court on Monday ruled in favor of an African-American death row inmate in Georgia, finding that the prosecutor’s decision to strike all the African-American jurors was unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court on Monday ruled in favor of an African-American death row inmate in Georgia, finding that the prosecutor’s decision to strike all the African-American jurors was unconstitutional.

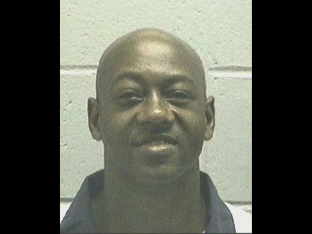

In 1987, Timothy Foster was convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of an elderly woman in Georgia. During the jury selection process, the state prosecutor exercised his preemptory strikes to remove all of the African-American prospective jurors.

Foster’s appellate counsel made an open records request and obtained the prosecutor’s notes which indicated that he intended to remove all the African-American prospective jurors based on race, not for race neutral reasons as the prosecutor claimed at trial. For example, included in the prosecutor’s notes was a list titled “[D]efinite NO’s” along with the names of all of the African-American prospective jurors. Also included in the file was an affidavit from a prosecution investigator who wrote, “If it comes down to having to pick one of the black jurors, [this one] might be okay.”

Writing for the Court’s 7-1 majority, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, ”The focus on race in the prosecution’s file plainly demonstrates a concerted effort to keep black prospective jurors off the jury.”

In 1986, the Supreme Court issued its opinion in the landmark case of Batson v. Kentucky which held potential jurors could not be removed based on race alone — the attorney must show a race-neutral reason for removing the juror.

The Supreme Court’s ruling means Foster’s death penalty conviction has been overturned and he will almost certainly get a new trial. Although, the opinion does note that Foster confessed to the killing when he was arrested back in 1986.

Justice Clarence Thomas was the lone dissenting judge, arguing that the Supreme Court never should have heard the case based on procedural grounds. Furthermore, Justice Thomas argued that the Court should not be in the business of second-guessing the state court nearly three-decades after the fact.

“But the Court today invites state prisoners to go searching for new ‘evidence’ by demanding the files of the prosecutors who long ago convicted them,” Thomas wrote. “If those prisoners succeed, then apparently this Court’s doors are open to conduct the credibility determination anew. Alas, every end is instead a new beginning for a majority of this Court.”