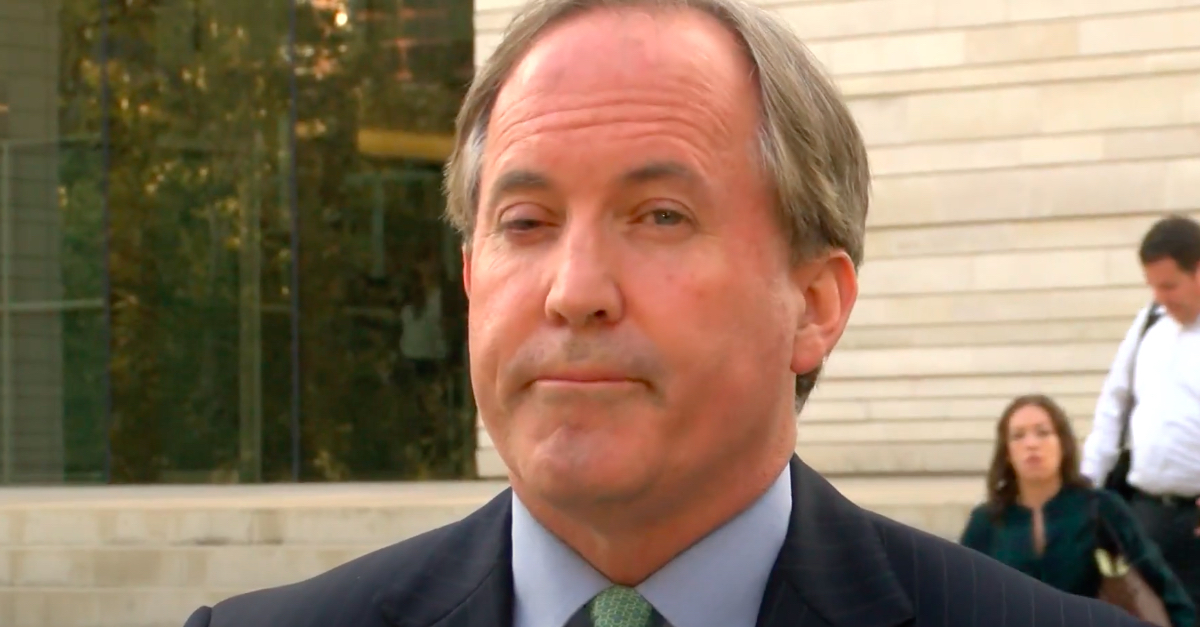

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton (R) was handed a scolding by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals on Wednesday, when the court ruled that Paxton had exceeded his legal authority to prosecute a fellow member of Lone Star State government.

In 2016, Zena Stephens, a Democrat and Texas’ first Black female sheriff, defeated a Republican challenger and was re-elected, in a county that narrowly voted in favor of Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in the same election. By early 2018, though, Stephens was indicted for accepting excessive campaign donations, courtesy of Paxton’s office. Stephens joined Vanessa Crawford (of Petersburg, Virginia) at the time as the only two Black women sheriffs in America.

Shortly after Stephens’ historic election, the FBI investigated and found that she received cash contributions in excess of $100, in violation of federal campaign-finance law. The FBI next referred its findings to the Texas Rangers, which presented the case to the Jefferson County District Attorney. That prosecutor’s office declined to prosecute Stephens, but referred the Texas Rangers to AG Paxton.

Paxton, who is himself under indictment, pursued the case against Stephens independently, presenting the case to a grand jury which in turn returned a three-count indictment. The first count was a violation of the Texas Penal Code for tampering with a government record (Stephens was accused of reporting a $5,000 individual cash contribution in the political contributions of $50 or less section of an official report). The second and third counts charged violations of the Texas Election Code for unlawfully accepting two contributions over the $100 limit.

Stephens filed a motion to quash the indictment on the grounds that Paxton lacked legal authority to unilaterally prosecute her. She argued that the attorney general has no authority to independently prosecute violations of the Penal Code, and that the Election Code’s delegation of authority to the AG amounted to an unconstitutional violation of separation of powers.

The trial court agreed with Stephens that the AG lacks the power to prosecute Penal Code violations, and quashed Count I of the indictment. That court, however, left Counts II and III in place. Both Stephens and Paxton appealed, and the First Court of Appeals sided with Paxton, ruling that he had the authority to bring all three counts against Stephens.

Texas’ highest court, however, reversed and sided 8-1 with Stephens, ruling that Paxton has no authority to unilaterally prosecute individuals.

The Texas attorney general’s duties, explained Judge Jesse McClure writing the 22-page opinion for the court’s majority, are enumerated in the state constitution. Those duties are limited to chartering and overseeing the actions of corporations, and providing legal advice to the governor and other executive officers. “Notably absent from these enumerations,” wrote McClure, “is a specific grant of authority to the Attorney General concerning the prosecution of criminal proceedings.” McClure underscored the wrongness of Paxton’s actions, writing, “Further, the Constitution already grants this authority to county and district attorneys.”

McClure also dismantled Paxton’s argument that the source of his authority to prosecute Stephens is in the state constitution’s language that the attorney general may “perform such other duties as may be required by law.” The power to prosecute is already delegated to county and district attorneys, reasoned the court. Calling the lower court’s misconstruing of the “other duties clause” “absurd,” McClure offered an example:

If we were to adopt the reasoning of the court below, then the Legislature could grant the Water Development Board with prosecutorial authority. Perhaps this example is extreme, but it certainly emphasizes how relying on “other duties” would render meaningless the separation of powers.

The judge continued, clarifying the need for Paxton and his successor attorneys general to stay in their lanes:

Therefore, while there are some permissible overlapping duties, the Constitution specifically separates the powers of the branches. Any attempt to overlap the Attorney General’s constitutional duties with county and district attorneys’ constitutional duties in the sense of a Venn diagram of sorts is unconstitutional. Practically speaking, any overlap is necessarily invitational, consensual, and by request: a county or district attorney must request the assistance of the Attorney General.

Judge Kevin Yeary, the lone dissenter, penned an 18-page opinion in which he said he would have deferred to the state legislature, which “has generally authorized the AG to participate in criminal prosecutions,” and could authorize additional authority.

Ken Paxton immediately criticized the outcome via tweet on Wednesday, writing that thanks to the ruling, “Soros-funded district attorneys will have sole power to decide whether election fraud has occurred in Texas,” and predicting that “This ruling could be devastating for future elections in Texas.”

Now, thanks to the Texas Criminal Court of Appeals, Soros-funded district attorneys will have sole power to decide whether election fraud has occurred in Texas. This ruling could be devastating for future elections in Texas. pic.twitter.com/guARe4zoln

— Attorney General Ken Paxton (@KenPaxtonTX) December 15, 2021

Russell Wilson II, Stephens’ attorney, celebrated the ruling, telling press:

Hats off to the court of criminal appeals for following Texas constitutional law. It’s a victory for not only Zena Stephens but for all elected officials in the state of Texas. And a reminder that the language of the Texas Constitution must be followed even by the attorney general.

Paxton himself faces felony fraud charges pending in Collin County, Texas. The case against him alleges that Paxton lured investors into a stock deal without disclosing his personal interest while he was a member of the Texas legislature. Paxton has denied all wrongdoing.

[screengrab via YouTube screengrab]

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]