Libertarian Republican Rep. Justin Amash (R-Mich.), over the weekend, said what fellow Republican lawmakers in Congress have not and supposedly will not: the Mueller Report shows that President Donald Trump committed impeachable offenses. For this, Trump lambasted Amash on Twitter and called him a “total lightweight,” but Amash doubled down on Monday.

Amash criticized the “several falsehoods” in arguments made by defenders of the president. Amash highlighted four defenses in particular and responded to each. The defenses were: There were no underlying crimes; an obstruction of justice offense requires an underlying crime; the president can end any investigation he deems “frivolous”; impeachment requires a “statutory crime or misdemeanor.”

“People who say there were no underlying crimes and therefore the president could not have intended to illegally obstruct the investigation—and therefore cannot be impeached—are resting their argument on several falsehoods,” Amash began.

Let’s examine these arguments and Amash’s commentary about them.

Claims 1 and 2: “There were no underlying crimes” and that’s what obstruction requires.

Amash said that the claim that there were no underlying crimes is undermined by the fact that “there were many crimes revealed by the investigation, some of which were charged, and some of which were not but are nonetheless described in Mueller’s report.”

But even if it was true that there were no “underlying crimes,” per Amash, that has no bearing on whether an obstruction of justice offense was committed.

Here Amash might as well have been responding to Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani, who has made this argument repeatedly. Trump nemesis George Conway, White House counsel Kellyanne Conway‘s attorney husband, recently took Giuliani to task for this argument by saying “stop it with the garbage, Rudy” — and then some.

“There’s a section of the DOJ manual that nicely captures what obstruction of justice is about. It’s got nothing to do with whether there’s an underlying offense,” Conway said. “It’s all about whether someone is trying to wrongly influence a participant in federal proceeding.”

“There doesn’t have to be an underlying offense; the proceeding can be about trying to figure out whether there was an underlying offense. This isn’t hard,” he added. “And … there’s also a whole section of the manual devoted to the basic proposition that obstruction doesn’t have to be successful to be obstruction.”

Conway then linked to the DOJ’s criminal resource manual to back up his analysis:

Sections 1512 and 1513 eliminate these categories and focus instead on the intent of the wrongdoer. If the illegal act was intended to affect the future conduct of any person in connection with his/her participation in Federal proceedings or his/her communication of information to Federal law enforcement officers, it is covered by 18 U.S.C. § 1512. If, on the other hand, the illegal act was intended as a response to past conduct of that nature, it is covered by 18 U.S.C. § 1513.

Amash essentially echoed Conway’s thoughts on Monday.

“In fact, obstruction of justice does not require the prosecution of an underlying crime, and there is a logical reason for that. Prosecutors might not charge a crime precisely *because* obstruction of justice denied them timely access to evidence that could lead to a prosecution,” Amash said. “If an underlying crime were required, then prosecutors could charge obstruction of justice only if it were unsuccessful in completely obstructing the investigation. This would make no sense.”

In other words, it’s about intent not success.

Claim 3: The president can without question shut down any investigation.

Amash said that those making this argument are implying that Trump “should be permitted to use any means to end what he claims to be a frivolous investigation, no matter how unreasonable his claim.”

“In fact, the president could not have known whether every single person Mueller investigated did or did not commit any crimes,” Amash responded.

Harvard Law Professor emeritus Alan Dershowitz, a frequent defender of the president, previously argued Trump was acting within his authority as head of the executive branch — unlike one Richard Nixon — when he fired former FBI Director James Comey.

“The act itself has to be illegal. It can’t be an act that is authorized under Article Two of the Constitution,” Dershowitz said. “Nixon obstructed justice because he acted outside his authority — destroying evidence, paying hush money, ordering his subordinates to lie to the FBI.”

Trump also asked Comey to let go of an investigation into Michael Flynn.

With obstruction, a prosecutor needs to be able to prove “corrupt intent” beyond a reasonable doubt. As Special Counsel Robert Mueller noted, there needs to be an “obstructive act,” a “nexus between the obstructive act and an official proceeding” and “corrupt intent.”

“The word ‘corruptly’ provides the intent element for obstruction of justice and means acting ‘knowingly and dishonestly’ or ‘with an improper motive,’” the Mueller report explained.

Trump’s lawyers argued, as Dershowitz did, that that the President “cannot obstruct justice by exercising his constitutional authority to close Department of Justice investigations or terminate the FBI Director.” They also said that Trump’s actions over the course of the investigation could be attributed to him being upset about a cloud hovering over his presidency for something he didn’t do (i.e. conspiring with Russia).

It seems Amash is saying that this is not — and should not be — considered a sufficient or acceptable reason to shut down an investigation, attempt to shut down an investigation or fire the person running it when they don’t do what was asked. After Comey was fired, now-former Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein appointed Mueller as special counsel.

It is true, though, that there are “no statutory conditions on the President’s authority to remove the FBI Director.”

Claim 4: An impeachable offense must be a jailable crime.

Lastly, Amash said that defenders of the president imply that “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” — the Constitution’s description of impeachable offenses — “requires charges of a statutory crime or misdemeanor.”

“In fact, ‘high Crimes and Misdemeanors’ is not defined in the Constitution and does not require corresponding statutory charges,” Amash said. “The context implies conduct that violates the public trust—and that view is echoed by the Framers of the Constitution and early American scholars.”

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) once took Amash’s stance on this issue — 20 years ago, when the president being investigated was Bill Clinton.

“[Y]ou don’t even have to be convicted of a crime to lose your job in this constitutional republic,” Graham said. “If this body determines that your conduct as a public official is clearly out of bounds in your role because […] Impeachment is not about punishment, impeachment is about cleansing the office.”

“Impeachment is about restoring honor and integrity to the office,” Graham added.

Additional context

The Amash-Trump feud ignited on Twitter over the weekend when Amash said that he believed the Mueller Report detailed impeachable offenses, making him the first Republican member of Congress to say so.

“In fact, Mueller’s report identifies multiple examples of conduct satisfying all the elements of obstruction of justice, and undoubtedly any person who is not the president of the United States would be indicted based on such evidence,” Amash said. “Under our Constitution, the president ‘shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.’ While ‘high Crimes and Misdemeanors’ is not defined, the context implies conduct that violates the public trust.”

But the Amash criticism also said that Attorney General William Barr misrepresented the findings of the Mueller Report in advance of the report’s release. In emphasizing his point, Amash referred to his own analysis as his “principal conclusions,” a clear reference to Barr’s four-page later on Mueller’s “principal conclusions.”

“In comparing Barr’s principal conclusions, congressional testimony, and other statements to Mueller’s report, it is clear that Barr intended to mislead the public about Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s analysis and findings,” Amash said. “Barr’s misrepresentations are significant but often subtle, frequently taking the form of sleight-of-hand qualifications or logical fallacies, which he hopes people will not notice.”

“Contrary to Barr’s portrayal, Mueller’s report reveals that President Trump engaged in specific actions and a pattern of behavior that meet the threshold for impeachment,” he added.

As noted in the opening, President Trump responded by calling Amash a “total lightweight who opposes me and some of our great Republican ideas and policies just for the sake of getting his name out there through controversy.”

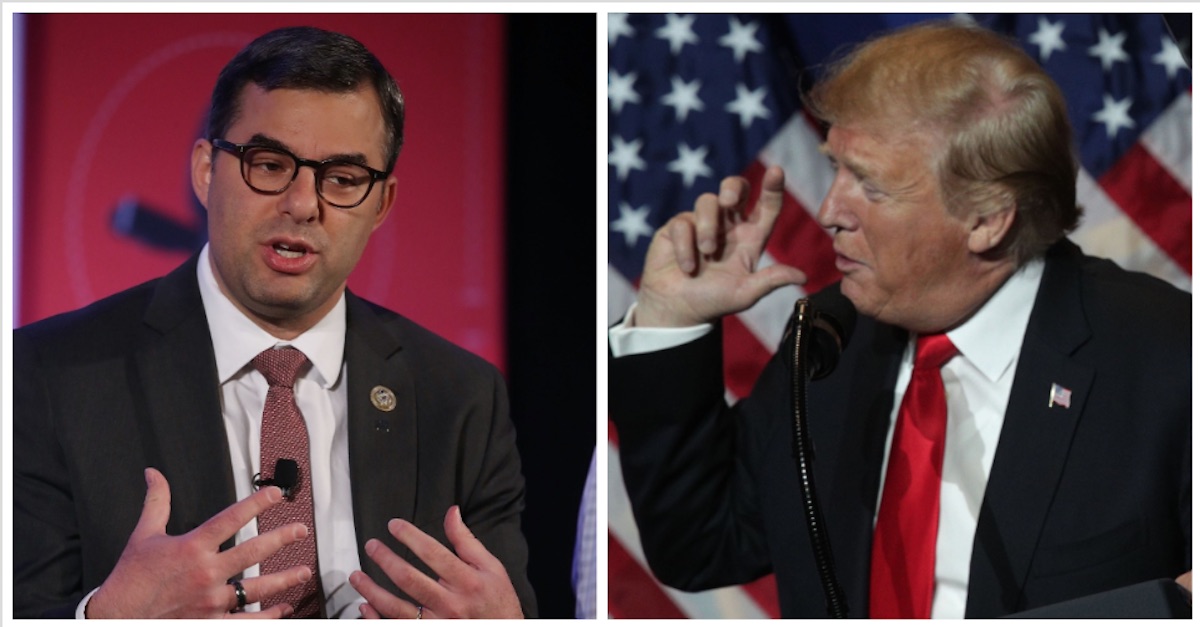

[Images via Mark Wilson/Getty Images, Alex Wong/Getty Images]

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]