The deadly shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida continues to be felt around the country, particularly after information came out showing that four members of the Broward County Sheriff’s Office were apparently at the scene — and did nothing.

The deadly shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida continues to be felt around the country, particularly after information came out showing that four members of the Broward County Sheriff’s Office were apparently at the scene — and did nothing.

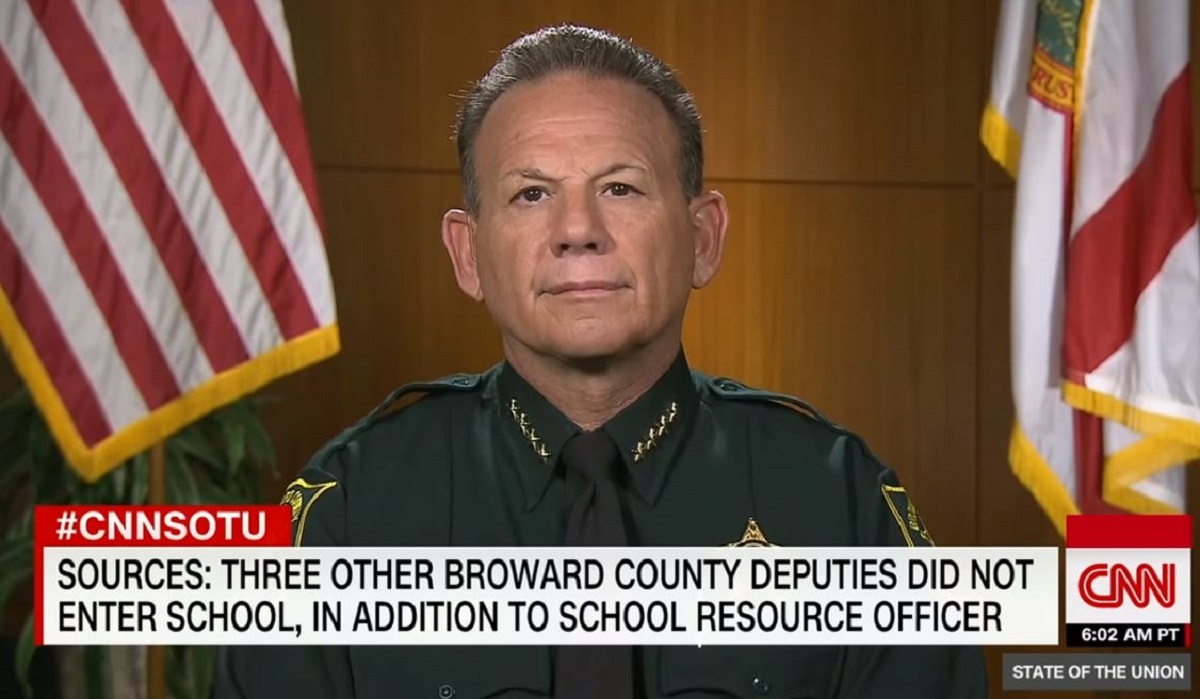

Scot Peterson, an armed school resource officer, reportedly was outside the school when the shooting took place, but did not go inside to stop the shooter, despite having received training on how handle active shooter situations. Peterson was suspended and then resigned. Reports later indicated that three other Sheriff’s deputies were on the scene, but did not go inside the school. Instead, they opted to remain behind their vehicles, guns drawn.

This reported failure to act has led Florida Governor Rick Scott to call for an investigation into the Sheriff’s Office. As for the victims and their families? The law could make it difficult for them to get justice.

Georgetown Law Professor Randy Barnett noted on Twitter that there are difficulties in holding law enforcement officials accountable in these types of situations. For starters, he says, there is no constitutional duty to protect. He cites the 1989 decision in DeShaney v. Winnebago County Department of Social Services, where the Supreme Court ruled that state officials could not be held liable after receiving reports of child abuse and not removing the boy from the home, only for him to be severely beaten and injured. The Court’s rationale was that while the government cannot actively deprive a person of life, liberty, or property without due process, that’s not the same as failing to protect a person from someone else’s actions.

Of course, that same court decision acknowledges that there could be other issues involved, including state laws that may attach a duty to protect where a person has already volunteered to do so. On that note, an advisory opinion from the Florida Attorney Generals’ Office the same year as the DeShaney case said:

A law enforcement officer, including a police officer, has a legal duty to provide aid to ill, injured, and distressed persons who are not in police custody during an emergency whether the law enforcement officer is on-duty or acting in a law enforcement capacity off-duty.

The opinion goes on to explain that the standard of protection that must be provided by the officer is “to render such competence and skill as he or she possesses.”

This could be understood to mean that in a situation like the Parkland shooting, officers who were present had a duty to help those who were in danger; especially if they were trained to handle active shooter situations.

Despite this, however, even if the Sheriff’s Office could be held accountable for its failure, that doesn’t mean they will be, or that such accountability would be effective. Barnett notes in another tweet that juries often don’t rule against officers. This situation could very well be an exception, given the high-profile nature of the situation and what appears to be a glaring failure on the part of law enforcement. Still, Barnett, mentions, when government agencies have to pay the price, it’s the tax payers who foot the bill.

The problem with law enforcement liability is that it’s the innocent tax payers who ultimately pay. Juries won’t generally rule against cops. There there needs to be a way to hold departments responsible in ways that affects their budgets. Not sure how to strike the balance tbh. https://t.co/aT04Hv4hUF

— Randy Barnett (@RandyEBarnett) February 25, 2018

[Image via CNN screengrab]