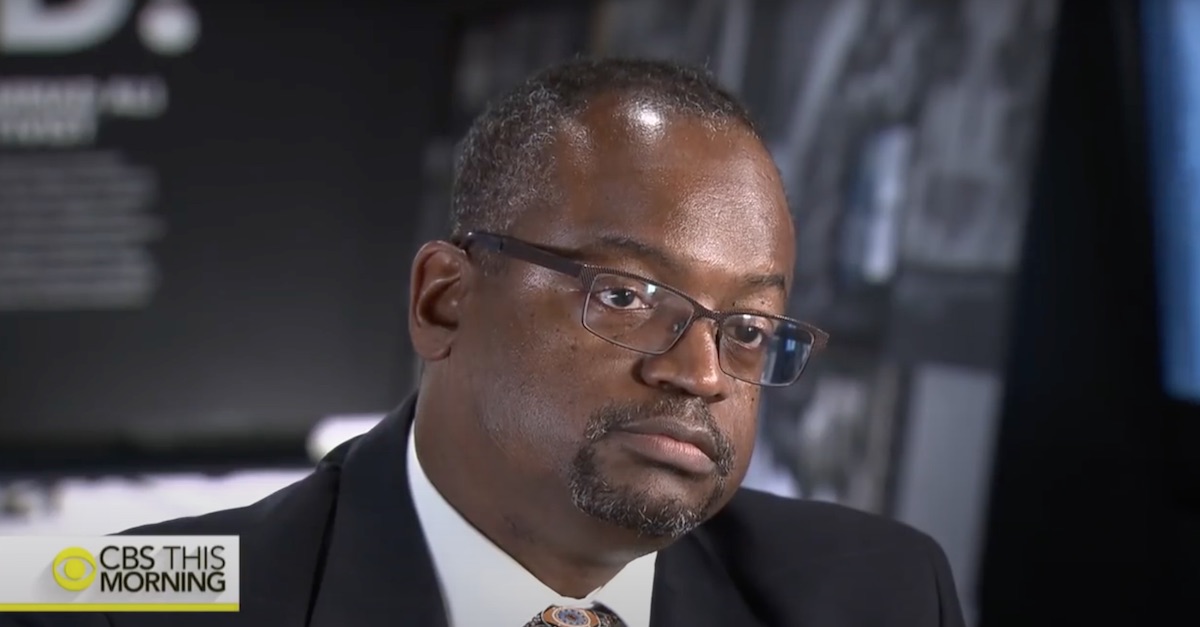

Judge Robert Wilkins

Federal appeals judges love hypotheticals. Hypotheticals often point to the absurdities in arguments made by attorneys in court. They also help judges understand how a decision in one case can drastically affect other types of cases in the future.

A hypothetical about racist prosecutors was raised by Judge Robert L. Wilkins of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit during arguments over whether his court should force a district court judge to dismiss the government’s case against former Trump National Security Advisor Michael Flynn. The hypothetical forced Principal Deputy Solicitor General Jeffrey Wall, whose job it is to represent the official interests of the United States government, to admit that judges should allow prosecutors to drop charges against white officers accused of violating the civil rights of black victims.

Judge Wilkins, who is black, was appointed by President Barack Obama to the district court bench in 2010 and to the D.C. Circuit in 2014. Two decades earlier, Wilkins was a plaintiff in Wilkins v. Maryland State Police, the 1992 lawsuit which popularized the phrase “driving while black.” The lawsuit challenged police practices of racially profiling and pulling over blacks who were driving expensive cars.

“Suppose you have a case where a federal law enforcement officer has pleaded guilty to criminal civil rights violation for using excessive force, and then the government says that they’ve uncovered some Brady evidence and are moving to dismiss under 48(a) after the guilty plea,” Wilkins asked. “Part of the reasoning of the authorities was that . . . they didn’t believe they would be able to prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt [because] the victim is black, the defendant law enforcement office is white, and they did not believe that the jury would believe the black victim over the white officer without corroborating evidence, and that’s unfortunate, but that’s the reality, and that was one of their reasons for dismissing.”

Wilkins then suggested as part of this theory, that maybe prosecutors would pull a sleight of hand to hide this racist reasoning. Maybe “they thought that wouldn’t play well, so they didn’t say that in the motion, they just said the exculpatory evidence was the reason they’re dismissing. Is that proper?”

Wall responded that in this scenario, where an overt legal motive about exculpatory evidence was being used to hide an ulterior racist motive, should still result in the court going along with the racist prosecutor. He said the motion to dismiss should be granted, in essence letting the hypothetical white officer who admitted to civil rights violations off the hook as a matter of law.

“I certainly hope that the government hasn’t ever filed a motion like that, and I’m not aware of it,” Wall said. “But even then, yes, I think the court should have to grant it . . . the government . . . no longer wants to proceed.”

Wall said there would be other remedies. “What you would see is . . . other defendants walking in, attaching that motion, and bringing Armstrong claims, saying the government is making racially-based decisions in its prosecutions, and based on your hypo, they’d have pretty good grounds for that.”

Wilkins, however pushed back. Rule 48(a) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, which are at issue in the Flynn prosecution, states that dismissal can only occur “with leave of court.” What that means precisely is up for argument; Flynn’s attorneys and the solicitor general’s office say it gives the judge very little latitude to probe into matters of perceived injustice because, ultimately, it is the job of the Executive Branch — in Flynn’s case, that’s the Trump Administration; in the hypothetical, that’s the racist prosecutor — to actually prosecute cases.

Wilkins balked at the upshot of the argument that a judge in the hypothetical case of the racist prosecutor couldn’t dig into things to determine whether racist intent actually occurred.

“You’d never know that it happened, right?” the judge asked. “If the district court hasn’t been allowed to ask . . . you’d never know that it’s happened?”

Wall pivoted to discuss cases involving sweetheart deals with corporate defendants to springboard to this statement: “It isn’t to the courts to police whether the executive has pure or impure motives; the remedies for those occur in political and public arenas; retaliation from the other branches; dismissal of corrupt executive officials; even impeachment if it comes to it, but Rule 48 . . . is not the mechanism for policing the kind of harms that you’re worried about.”

In other words, the other branches, like the courts, are supposed to police bad executive conduct, but the courts don’t have the power under Rule 48 to actually police it.

Wilkins looped back to the issue a few minutes later. Wall again argued that a court would have to allow a racist prosecutor to drop a case against a white officer who admitted to illegally beating a black defendant because no case or controversy existed under Article III, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution.

“I don’t think the court can force the executive to keep that case alive in the absence of a case or controversy,” Wall said. “The reason your hypothetical has force is because it’s an unconstitutional motive . . . there’s nothing like that here” in Flynn’s case.

Wilkins kept pressing. He wanted to know if judges could use Rule 48(a) to investigate matters that were of clear concern to Congress, to the public, and to the press — and possibly to appoint a non-racist prosecutor to take over the matter.

“So why isn’t it the case that if the government makes a considered but racist decision, that it just does not want to have a white officer stand trial for excessive force on a black victim, that the district court can deny the motion and then the political chips can fall where they may, and perhaps under pressure from the public or Congress or whatever, the district court may not be able itself to force the government to prosecute the case, but maybe through the operation of the legislative branch, or other pressures from the public and the media, a new prosecutor is appointed and the case proceeds? Why isn’t that exactly what ‘leave of court’ should operate to do?”

“There’s no power to make the executive move forward with the trial; this isn’t the concern of Rule 48,” Wall responded.

“If the government can’t make the case go away, and the case is in limbo — while it’s in limbo, pressure could be brought to bear on the government to reconsider its decision? Right?” Wilkins asked.

Wall pointed to a decision by current U.S. Supreme Court justice Brett Kavanaugh dating to Kavanaugh’s time on the D.C. Circuit.

“As Judge Kavanaugh explained in Aiken, the remedy for that kind of an equal protection violation is to dismiss other cases; it’s not to compel the government to move forward with this prosecution,” Wall said.

The timely hypothetical was raised during the second week of protests surrounding the alleged murder of George Floyd by four Minneapolis police officers.

[Image via CBS This Morning screengrab]