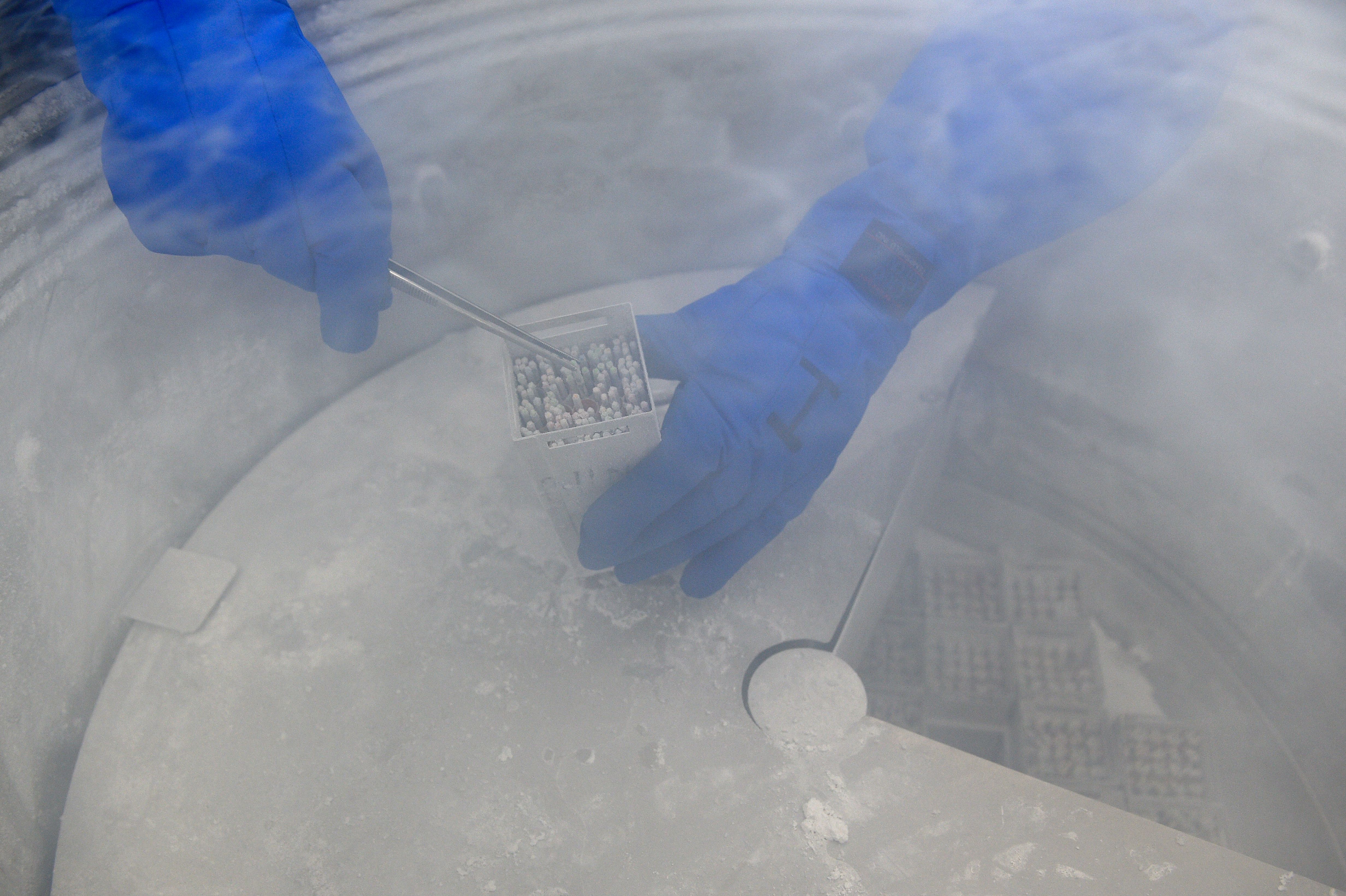

Egg and embryo storage is pretty common these days, but thankfully, accidents like those reported are quite rare. After frozen eggs or embryos are extracted, they are typically stored in liquid nitrogen tanks. Those tanks are supposed to be monitored closely with all sorts of surveillance and alarms that alert the facility about any changes in temperature. At the Cleveland fertility center, an equipment failure caused temperatures in the storage part of the facility to become too warm – and as a result, the eggs and embryos may no longer be viable.

As you’d expect, the lawsuits are already flying. Amber and Elliott Ash have filed a class action lawsuit against the Cleveland hospital. The Ashes had two embryos stored at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center’s suburban fertility clinic – a reproductive plan to conceive a sibling through in vitro fertilization (IVF) for their two-year-old son following Elliott’s cancer diagnosis in 2003. The couple says that as a result of the mishap, their embryos are now no longer viable, and are seeking an undisclosed amount in damages.

Assuming it actually moves forward in the litigation process, the Ash lawsuit (as well as the corresponding one that will likely be filed in California) could be groundbreaking. To date, there have only been a handful of similar lawsuits, and all have settled, resulting in no guiding case law. Furthermore, any similar lawsuits have been the result of loss of just a few embryos—and not the wide scale damage to hundreds of similarly-situated plaintiffs we see in the current litigation.

The Ash complaint described the hospital’s failure to maintain the embryos as “what can only be characterized as gross negligence and an utter breach of trust, decency, and responsible stewardship,” that “destroyed the hopes, dreams, and futures of hundreds, if not thousands of prospective Ohio parents and families.” What is potentially novel in the case is that the plaintiffs allege not only negligence and breach of contract, but also bailment. A claim for bailment requires exactly what was plead in the court filing: that, “Plaintiffs and the other Class members delivered to Defendants for safekeeping personal property to be safely and securely kept and to be redelivered to them on demand.”

The law of bailment – essentially, claims for damage incurred during storage — is perhaps one of the driest subjects ever to grace the pages of the bar exam; however, in this context, it may be a vehicle for heated debates, moral judgments, and groundbreaking legal precedent. In order for a plaintiff to win a bailment claim, he or she must prove that personal property was handed over to someone. Declaring eggs or embryos to be “personal property” might ruffle a few feathers and have lasting impact.

The Ash case won’t be the first time a court ever grappled with the status of an embryo or egg; in the past, courts have sometimes declared such items, “entities deserving of special respect” – essentially a non-legal term of art that is meant to convey both the great value of the items, as well as the uniqueness of the issue of their status. In past cases, though, courts had n deciding the fate of the embryos or eggs – such as in Sofia Vergara’s highly-publicized battle for custody of her frozen embryos. Never before has a court decided what an embryo or egg was in the past tense.

Law & Crime spoke today with attorney Alix Rogers, a specialist in bioethics and the law fellow at Stanford Law School’s Center for Law and the Biosciences. Rogers explained the unusual situation that may come to exist with regard to the legal status of embryos in particular:

“Most states consider sperm and eggs legal property. By contrast, the legal status of embryos is uncertain. Some state courts have classified them as property, whereas others, such as California, have classified them as “non-property entities that deserve special respect”. This could lead to a strange situation wherein an individual could recover on property based legal actions, such as bailment or conversion, for their stored eggs, but not for their stored embryos. This does not mean that patients with embryos will not recover, it just means that their claim will be based upon more complicated legal avenues such as emotional distress, negligence, or breach of contract.”

Because there is such a dearth of case law on the matter, jurisdictions are likely to look to one another for guidance. Thus, the Court of Common Pleas of Cuyahoga County, Ohio may find itself in the position to write the first page in what is sure to be a lengthy legal book.

The court could take the easy road and opt out of the embryos-as-property issue altogether, deciding the case on other grounds. The claims for negligence and breach of contract, for example, require no such finding that the embryos and eggs at issue constituted personal property. But even if the court dodges the bailment question, this case could become intensely significant on the issue of damages. Specifically, the question “for what must the plaintiffs be compensated?” must be answered. The court’s calculus in determining damages, while not strictly binding on other jurisdictions, will certainly be examined closely. Questions such as whether the court would include the cost of IVF treatments (roughly $8,000-$10,000 per round), the value of potential parents’ lost opportunity, or compensation for pain and suffering would almost certainly arise. Whether the Ash plaintiffs would be compensated for their “destroyed hopes, dreams, and futures” or whether the court would calculate simple contract damages for the storage price is uncertain, and would be some pretty compelling legal news.

Rogers explained how a ruling on damages might influence future litigation:

“Given that these cases have historically settled, the amount of damages and compensation that clinics offer is almost never made public. A trial with publicly available figures could therefore benefit future individuals, even those involved in arbitration or settlements.”

The class action lawsuit filed on behalf of the hundreds of devastated individuals and couples is bound to provide, at best, imperfect compensation for a devastatingly amorphous loss. As medical science continues to advance, we will continue to face legal questions that raise complex moral, philosophical, and ethical questions. Law & Crime will continue to follow this litigation as it advances through the Ohio court system.

(LLUIS GENE/AFP/Getty Images)

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.