Is there nothing new under the sun? What if we told you that President Donald Trump‘s approach to Special Counsel Robert Mueller and the Russia investigation was something right out of the Ulysses S. Grant playbook?

Grant, the 18th president of the United States and Union Army general in the Abraham Lincoln years, responded to the first special prosecution in U.S. history in a remarkably familiar way, even if the origins of the probe were different.

The “Whiskey Ring Scandal,” as history tells us, resulted in the appointment of the first special prosecutor, John B. Henderson. One key difference between then and now is that Grant actually appointed Henderson so as to appear impartial and expressed his confidence in the investigation, regardless of where it led. That changed, however, when the investigation started to hit closer to home.

The National Archives say that GOP operatives formed the Whiskey Ring in 1871 to “raise funds for political campaigns in Missouri and other western states” when Grant’s reelection appeared to be in doubt. Grant had his Supervisor of Internal Revenue Gen. John McDonald solve the problem, and what ensured was “[i]llicit whiskey money [beginning] to fill campaign stores and finance partisan newspapers to print articles favorable to the Grant administration.”

Huh? Collusion/payoffs/use of the press for the purpose of influencing the election? Hmm.

Per the National Archives, on the scheme:

Complex in detail, but simple in design, the ring made money by selling more whiskey than it reported to the Treasury Department. Its success required collusion at every point of the production, distribution, and taxation process. To pull it off, ring leaders recruited, impressed, and blackmailed distillers, rectifiers, gaugers, storekeepers, revenue agents, and Treasury clerks into the operation. They split the seventy-cents-a-gallon tax money they had stolen a number of ways. U.S. Attorney David P. Dyer, the man who would one day prosecute the whiskey thieves, later explained the arrangements of the ring to congressional investigators:

“They kept an account at the distillers of all the illicit whisky that was made, and the gaugers and store-keepers were paid from one to two dollars for each barrel that was turned out . . . and every Saturday reported to the collector of the ring the amount of crooked whisky, and either the distiller or the gauger paid the money over as the case might be. The arrangement between distiller and rectifier was that thirty-five cents . . . was divided between him and the rectifier. That division was made by the distiller selling crooked whisky . . . at seventeen cents a gallon less than the market-price. That is how the rectifier got his share of the amount retained by the distiller. The amount paid to the officers was on each Saturday evening taken to the office of the supervisor of internal revenue and there divided . . . and distributed among them.”

When Grant appointed Benjamin Bristow as the Secretary of the Treasury in 1874, he actually appointed a man with a mind to reform. In particular, Bristow wanted to expose the Whiskey Ring and put pressure on both Grant and his officials to do something about them.

Bristow made the destruction of the whiskey rings (rings for the scheme operated in a number of different cities) his personal and political crusade, but early efforts to unravel the corruption failed. He later recounted, “Although I did receive further evidences of the existence of combination and conspiracies to defraud the Government, in which there was reason to believe that certain officers of the Government were participants, I still was unable through the medium of the Internal Revenue office to a get hold of a thread by which we could be enabled to follow it to the end.”

Bristow dug deeper and accused Grant’s private secretary Gen. Orville E. Babcock of being behind the conspiracy — “The law, in the form of Bristow, was now at Grant’s door, poised to apprehend the President’s closest and most trusted aide— if not the President himself.” Does this remind anyone of Michael Cohen?

Lawfare editor Benjamin Wittes pointed out some other striking historical facts: When his authority was questioned, Grant orchestrated the firing of special prosecutor Henderson (Henderson was replaced by James Broadhead); Grant made sure that his sons were immune; he “railed against flipping witnesses”; Bristow, both punching bag and reformer, resigned.

https://twitter.com/benjaminwittes/status/1077965267899162626

(2) He drew a red line around his sons and demanded that reports that they were investigative subjects be rebutted.

— Benjamin Wittes (@benjaminwittes) December 26, 2018

(3) He railed against flipping witnesses and basically instructed the attorney general to advise Midwestern U.S. attorneys not to let anyone flip in exchange for immunity.

and…— Benjamin Wittes (@benjaminwittes) December 26, 2018

(4) His treatment of his Treasury Secretary, Benjamin Bristow, really has a bullying Rosenstein/Sessions-like feel to it. Bristow eventually resigned citing “withdrawal of your confidence & official support.”

— Benjamin Wittes (@benjaminwittes) December 26, 2018

Grant actually volunteered to testify at trial in the probe. Although Babcock was acquitted in the Whiskey Ring Scandal, he did resign from his post. Nonetheless, more than 200 people were indicted and more than 100 people were convicted. Millions of tax dollars were recovered by the government. One description of Grant’s legacy post-scandal was also jarring:

Though Grant himself never betrayed his reputation for honesty, his legacy as president was marred by the corruption of his associates, appointees and trusted friends—as the saga of the Whiskey Ring Scandal clearly demonstrates.

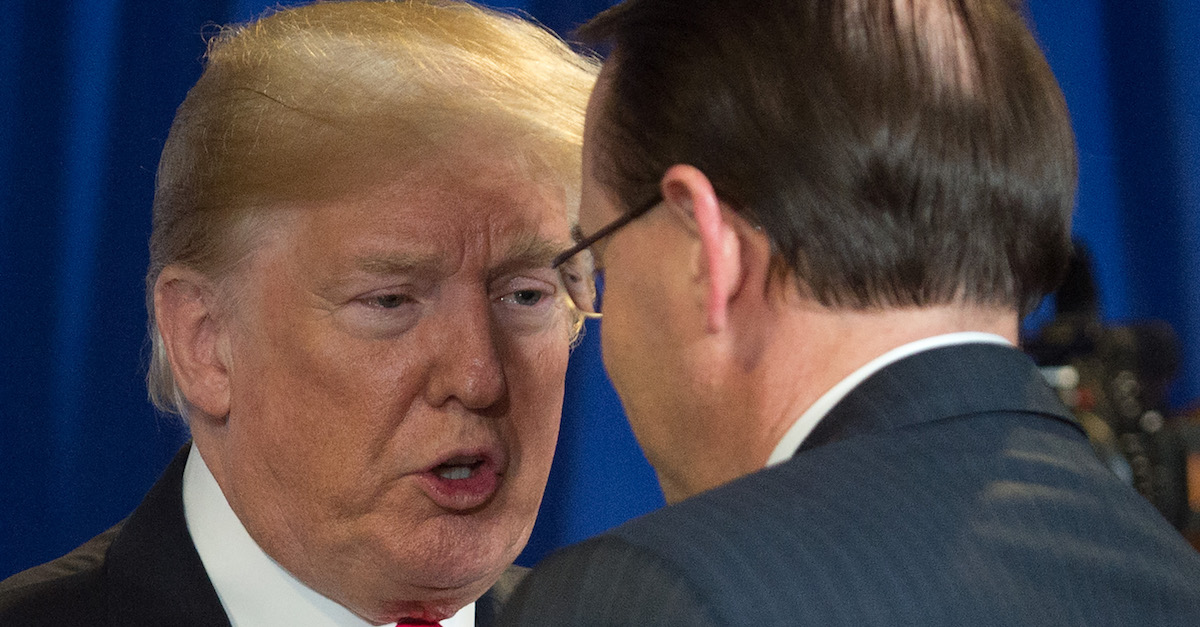

[Image via Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images]