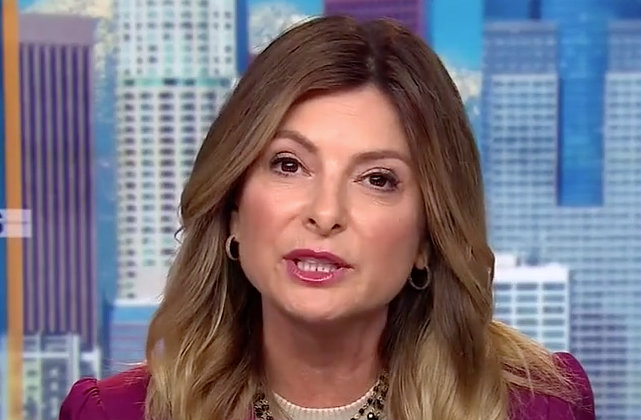

The allegations that famed feminist attorney Lisa Bloom offered Trump accusers serious cash is sending shock waves especially in conservative circles. Despite insistence by the accusers that the stories are accurate, incentives for making the claims against then candidate Donald Trump inevitably raise questions. According to the report, one accuser, who decided never to recount her story, was offered as much $750,000 to tell-all.

The allegations that famed feminist attorney Lisa Bloom offered Trump accusers serious cash is sending shock waves especially in conservative circles. Despite insistence by the accusers that the stories are accurate, incentives for making the claims against then candidate Donald Trump inevitably raise questions. According to the report, one accuser, who decided never to recount her story, was offered as much $750,000 to tell-all.

According to the Hill, Bloom arranged, “a donor to pay off one Trump accuser’s mortgage and attempt[ed] to secure a six-figure payment for another woman who ultimately declined to come forward after being offered as much as $750,000.”

While much outrage has been focused on the large monetary sums offered, there are a few angles of the story that are not getting much attention, and could ultimately have the most serious legal consequences for those involved.

During the course of Bloom’s interaction with one of the accusers, she reportedly told her this:

The figured jumped to $200,000 in a series of phone calls with Bloom that week, according to the woman. The support was promised to be tax-free and also included changing her identity and relocating, according to documents and interviews. (our emphasis)

Now, there is no indication in the story that the woman ultimately received the funds. However, if someone were to receive $200,000 to make a media appearance, and come forward with allegations against Donald Trump, there is little doubt that state and federal tax authorities would consider that taxable income. If the income was not reported to the IRS, the woman could get in serious legal trouble, and so might an attorney if he/she was involved in arranging any kind of illegal tax-free workaround.

Robert Mckenzie, a tax attorney, explained to Law&Crime:

Damages for emotional distress are taxable on any amount above unreimbursed medical and psychological expenses. From the article it is not clear if the women had those damages. Another complication is that the money is not coming from the accused but apparently enemies of the accused. They are being compensated for there disclosures not the harm caused by the accused. In my view that would make it likely that all payments could be characterized as taxable.

What we don’t know- were there other women who were promised and received this kind of deal?

In another case reported to The Hill, a donor paid off Trump accuser Jill Harth’s $30,000 mortgage. Could this be considered a campaign donation? There are clear indications that the payment was politically motivated, and made with the intent to expose, and possibly stop Trump from being elected. Could the payments be considered unreported campaign contributions, and federal election campaign action violations?

According to the Federal Election Commission, a contribution is anything of value given, loaned or advanced to influence a federal election.

We asked campaign law expert Paul Ryan from Common Cause:

So the answer is no, “if a donor gave a woman who came forward $30,0000 to pay off her mortgage,” that would not be considered a campaign contribution subject to reporting requirements.

If the accusers and Bloom were coordinating with the Clinton campaign or super PAC, and there was an agreement between the accusers and the political committee that the purpose of the accusers coming forward was to influence the election, then an argument could be made that the donors who gave money to the accusers were actually making a reportable in-kind contribution to the political committee. But that seems like a stretch of a legal argument under the facts presented in the Hill article. The article states explicitly that the Clinton campaign was not involved in any of this. And though there are some passing references to one or more super PACs, there are no facts in the article indicating that a super PAC was coordinating all of this and, therefore, receiving a reportable in-kind contribution.

When Law&Crime emailed Bloom about some of the legal concerns, she sent back a lengthy statement that she had prepared for the media. She pointed out that in the Hill article both the woman and Harth, who were friends, stressed that she “never asked them to make any statements or allegations except what they believed to be true.”

As for the donor allegations, Bloom wrote, “I can say unequivocally that we did not communicate with Hillary Clinton nor anyone from her campaign. As an attorney I was obligated to relay those offers of funds for relocation to a safer community and round the clock security, and I was happy to do it.”

When assessing the motivation for making the accusations, it is important to remember that Jill Harth actually filed a lawsuit, which she later dropped, against Trump. In fact, Law&Crime was the first to dig up the documents surrounding Harth’s 1997 lawsuit and when we published our story, Harth threatened to sue us for using photos from her social media accounts for our article. We eventually negotiated with Lisa Bloom to pay Harth a small fee to license those photos (and one other).