Net neutrality is dead. Long live the principle as it exists in our minds.

Since the Federal Communications Commission (“FCC”) voted to repeal 2015’s Open Internet Order just this afternoon-and the net neutrality protections it enshrined–social media has been all abuzz as to what happens next. Let’s take look.

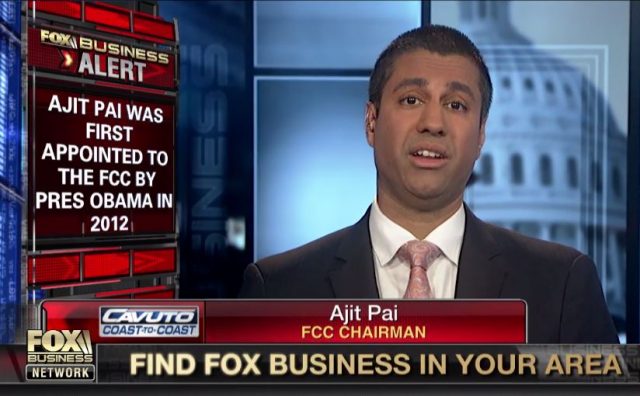

First, the new rules will be published in the Federal Register, setting their effective date. After that, things get actionable. A plaintiff could then ask the FCC to reconsider or stay their own decision but this course all-but certainly wouldn’t lead anywhere because FCC Chairman Ajit Pai—who appears in videos with Pizzagate conspiracy theorists–clearly doesn’t care what anyone thinks about anything.

The best course of action would be to file an appeal immediately in the U.S. Court of Appeals. The obvious circuit court candidate here would be the D.C. Circuit–the appellate court which typically hears such agency cases.

The framework for a potential plaintiff would more or less look like this:

(1) A private party is negatively affected by the FCC’s rulemaking–you’ve got to have a negatively-affected party; (2) That party wants a court to review the agency’s action, pursuant to §706 of the Administrative Procedures Act (“APA”); (3) The agency will immediately file a motion to dismiss, claiming that its decision cannot be reviewed under the APA; (4) If the agency action can be reviewed, however, the reviewing court can reach the merits of the party’s claim—that there is something wrong with the agency action.

Let’s break that out and down a bit.

1. An advocacy organization fiercely opposed to the evisceration of the internet as we know it–like the Electronic Frontier Foundation–or perhaps users aggrieved by non-neutral network activity by ISPs would be the logical choices here (we’ll mostly ignore standing intricacies in this analysis for simplicity’s sake);

2. The moving party would need to specify their preferred form of relief. This would be the stage known as framing the complaint. It could be a very basic statement of facts and supporting documentation initially. The most important thing here would be the request to set aside the FCC’s new rule–the revocation of the 2015 Open Internet Order.

Additionally, the moving party would have to specify the legal basis for setting aside the FCC’s new rule. There are plenty of options here–and all of them are extremely complicated. The most likely choice, however–which is also the most tried-and-true method of setting aside agency rule-making–is to argue that the FCC’s action was “Arbitrary and Capricious” which is something people tend to say a lot, but is also an extremely precedent-ridden legal term of art. Here’s the Supreme Court’s test for that:

Normally, an agency [decision] would be arbitrary and capricious if the agency has [1] relied on factors which Congress has not intended it to consider, [2] entirely failed to consider an important aspect of the problem, [3] offered an explanation for its decision that runs counter to the evidence before the agency, or [4] is so implausible that it could not be ascribed to a difference in view or the product of agency expertise.

3. Well, this one is actually pretty self-explanatory. It’s not just that Ajit Pai is a conservative meme pretending to be an FCC commissioner–that much is true–but all administrative agencies claim their actions cannot be reviewed by courts or challenged by citizens as a matter of course. The administrative branch of government is pure Kafka for lots of reasons and the agencies’ typical posture here is…well..typical. The FCC will basically file a form letter that sets up the next battle.

4. Now, whether the agency’s action can even be reviewed by the court adjudicating the dispute is where most of the legal battle is actually going to be fought. This is where standing really comes into play. Here, a court would also look at ripeness concerns (whether something negatively has actually happened yet) and various issues related to the APA’s insulation around agencies that statutorily protect them from issuing rules in the absence of Congressional action.

But let’s short-circuit some of that mind-numbing legal minutiae and assume the moving party is able to get the merits of their claim before a court. At this point, the plaintiffs would have made it to the legal end zone–but it’s still most likely to end up like Colt McCoy‘s last stand as a Longhorn quarterback. That is, the pitfalls haven’t really ceased, they’ve just begun, because then the court will look to see if the FCC is entitled to Chevron deference. And for our purposes, that’s a fancy of saying the plaintiff is probably going to lose.

TL;DR–if you’re worried about net neutrality and want it back, don’t wast time with the courts, get up and organize for Congress to take action.

[image via screengrab]