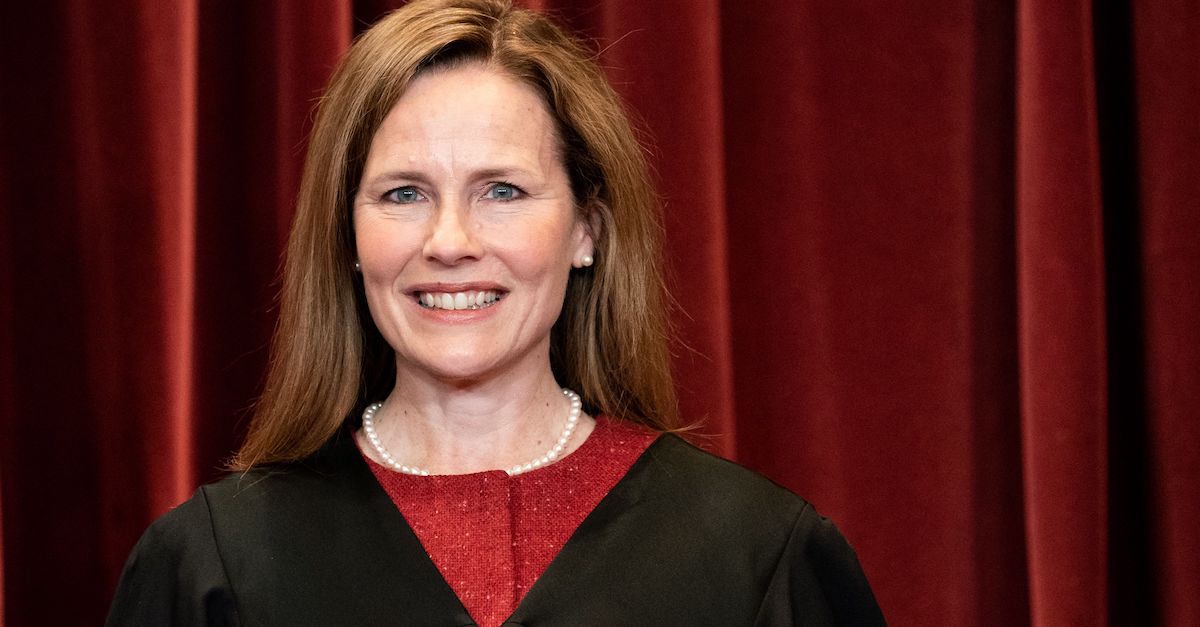

Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett stands during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021.

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Amy Coney Barrett denied without comment a conservative group’s attempt to block President Joe Biden’s student debt relief plan from going into effect. The denial came just one day after the request hit the high court’s docket.

The case was an emergency appeal on a ruling from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. Accordingly, the petition was officially before Barrett, who is the assigned justice for the region. Barrett could have referred the case to the full Supreme Court, but instead, denied the group’s appeal without further proceedings. The case — which was an appeal of the lower courts’ denial of a preliminary injunction while the full litigation works its way through the courts — was handled as part of what is widely called the Court’s “shadow docket.”

The petitioner group, the Brown County Taxpayers Association, argued that Biden improperly relied on a federal statute that was meant to provide assistance in the face of “national emergencies” — and that the pandemic is not such an emergency because it is over, as the president himself said.

BREAKING at SCOTUS: Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan has arrived on the shadow docket pic.twitter.com/DOK7HKQGFi

— Steven Mazie (@stevenmazie) October 19, 2022

Biden’s program is set to officially go into effect on Sunday, October 23, but the petitioners asked SCOTUS to issue an emergency injunction that would block the start while litigation proceeds in a lower court.

The petitioners summed up their problem with Biden’s debt-cancelation plan as follows:

The blow to the United States Treasury and taxpayers will be staggering—perhaps costing more than one trillion dollars. If this program goes forward as planned on Sunday, then the President will unilaterally spend roughly 4% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product. (emphasis in the original).

Still, “this is too expensive” is an insufficient legal argument, so petitioners framed their objection rather creatively by raising challenges based on separation of powers and the “major questions doctrine.”

Biden’s program forgives up to $20,000 in federal student loans for qualified borrowers. Legally, the administration accomplished this via the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students Act of 2003 (the “HEROES Act”), which allows the federal government to adjust the terms of student loan programs during national emergencies. In this case, the administration reasons that the COVID-19 pandemic is an emergency that underlies the change.

The petitioner group was clear in its message to the justices: the HEROES Act should only be used to help some students. From the group’s second question presented:

Does the Major Questions Doctrine prevent the President from relying on the HEROES Act, an act designed to support the “men and women of the United States Military,” 20 U.S.C. § 1098aa, to create a massive federal program of loan forgiveness for tens of millions of Americans?

Further, they contended, the COVID-19 pandemic is not the kind of “national emergency” that would empower Biden to take such sweeping action. “Respondents did not announce this program until nearly two-and-a-half years after the pandemic began and a few weeks after the President declared that ‘[t]he pandemic is over,'” petitioners argued in their brief.

“Even the White House’s own press release on the plan did not invoke a ‘national emergency,’ but merely mentioned in passing that the plan will ‘provide more breathing room to America’s working families as they continue to recover from the strains associated with the COVID-19 pandemic,'” the brief argued.

“A policy to ‘provide more breathing room’ to Americans ‘as they continue to recover’ from a respiratory virus hardly sounds like a ‘war or other military operation or national emergency’ denoted in the Act,” said the petitioners.

A preliminary hurdle

As in any viable lawsuit, the petitioners’ case must clear a significant preliminary hurdle in order to proceed: the taxpayers must prove that they have standing to sue. Generally, plaintiffs do not satisfy the standing requirement by simply arguing that a particular kind of government spending is imprudent or would increase taxes.

Under the 1968 case Flast v. Cohen, however, the Supreme Court has recognized taxpayer standing in a narrow set of circumstances. This exception to the general rule allows taxpayer plaintiffs to sue only when an enactment occurs under Congress’ taxing and spending powers and when the challenged action exceeds constitutional limitations of power. In other words, to establish standing, the plaintiffs must prove not just that they are financially harmed, but also that the expenditure itself is constitutionally improper.

In petitioners’ question presented to SCOTUS, they bluntly framed their suggestion that perhaps the time has come for Flast to go:

May a taxpayer sue in federal court to prevent executive officials from unilaterally exercising the Constitution’s spending power in violation of “specific constitutional limitations,” Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83, 102–3 (1968), or is the taxpayer-standing doctrine announced in Flast effectively a dead letter that ought to be overruled?

U.S. District Judge William Griesbach (a George W. Bush appointee) dismissed the case for lack of standing at the district court level. The Seventh Circuit affirmed, and Barrett’s denial now means that the dismissal will stay in place. The practical result will be that Biden’s loan forgiveness plan will proceed as planned.

The petitioners argued that they must have standing, because without a successful challenge to Biden’s plan, “The President could send checks to everyone (or to carefully selected demographic groups) for any amount to achieve any political end.” Narrow though the taxpayer standing exception might be, they contended, this case presented precisely the challenge that meets the requirements under Flast.

They also went a step beyond, arguing that even if the justices found that their claim does not fall within Flast’s exception, the exception should simply be widened to allow their case to proceed.

At the now-failed preliminary injunction stage, petitioners argued that they should prevail for two reasons: the “major questions” doctrine; and that Biden’s plan violates separation of powers under the Constitution.

Separation of powers

The taxpayer group argued that student loan forgiveness amounts to an unconstitutional exercise of Congress’ spending power by the executive branch. In their brief, the petitioners said the plan will cause “a gargantuan increase in the national debt” that is “accomplished by a complete disregard for limitations on the constitutional spending authority.” They argued that the plan “tramples” the spending power and harms taxpayers by forcing them to shoulder over one trillion dollars in debt.

Petitioners reasoned that because spending is solely within the discretion of Congress absent delegation to the executive branch, Biden exceeds his constitutional authority by implementing a plan that amounts to a properly legislative function.

“Major questions” doctrine

To support its argument that authority to implement such a plan lies solely with Congress, petitioners argued that Biden’s move constitutes a “major question.” Under this rather amorphous judge-made framework, when a question of great political or economic importance is at stake, Congress must be specific in its delegation of authority to federal administrative agencies to regulate the matter.

The question, however, as Justice Elena Kagan articulated during a recent SCOTUS argument regarding an environmental regulation: “how big” does a question have to be in order to count as “major”?

Though the justices might have used the emergency appeal to work out the scope of Flast or “major questions,” Barrett’s ruling means that the Court will be silent on such matters for the time being.

Counsel for the petitioners did not immediately respond to request for comment.

Editor’s Note: This piece was updated from its original version to include Justice Barrett’s ruling Thursday.

[image via Erin Schaff/AFP via Getty Images]