The United States Supreme Court on Thursday made it more difficult for certain legal immigrants facing deportation orders to apply to a judge to review and possibly reverse those orders. In so ruling, the court held that a green card holder could be deemed not to meet certain timing requirements in the law because of old criminal activity which “need not be one of the offenses of removal.” The 5-4 decision, issued along the usual ideological lines, required the justices to engage in a complicated interpretation of a complicated statute, but it resulted in an opinion which makes it easier for the government to remove immigrants from U.S. soil.

Immigration law allows legal permanent residents scheduled for removal to apply to a judge to cancel their removal orders if they meet certain criteria. The criteria requires the immigrant to have been lawfully admitted for permanent residence for at least 5 years, to have resided in the United States continuously for 7 years, and to have not committed an aggravated felony. The statute also imposes a “stop-time rule” on the resident’s initial seven years during which a much broader range of offenses can stop the clock on the resident’s continual residency.

Andre Barton, a Jamaican national and a lawful permanent resident of the United States, was convicted in 1996 of a firearms offense for shooting his ex-girlfriend’s house. He was also convicted of separate drug offenses in both 2007 and 2008 for which the government sought his removal.

The federal government contended that Barton failed to accrue the requisite seven years of continuous residency because his 1996 conviction triggered the time-stop rule.

In response, Barton argued that the 1996 crimes did not trigger the rule because he was a permanent resident who had already been admitted to the country at the time of the crime and therefore could not be rendered inadmissible as a matter of law.

Writing for the majority, Justice Brett Kavanaugh took a straightforward statutory interpretation approach to the case, reasoning that Barton’s argument did not comport with the text of the statute.

“Removal is particularly difficult when it involves someone such as Barton who has spent most of his life in the United States,” Kavanaugh wrote. “Congress made a choice, however, to authorize removal of noncitizens — even lawful permanent residents — who have committed certain serious crimes … the immigration laws enacted by Congress do not allow cancellation of removal when a lawful permanent resident has amassed a criminal record of this kind.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor penned the liberal justices’ dissent, saying the majority was contradicting the statute.

“At bottom, the Court’s interpretation is at odds with the express words of the statute, with the statute’s overall structure, and with pertinent canons of statutory construction. It is also at odds with common sense,” she wrote. Sotomayor did not stop there:

[B]ecause of the Court’s opinion today, noncitizens who were already admitted to the country are treated, for the purposes of the stop-time rule, identically to those who were not—despite Congress’ express references to inadmissibility and deportability. The result is that, under the Court’s interpretation, an immigration judge may not even consider whether Barton is entitled to cancellation of removal—because of an offense that Congress deemed too trivial to allow for Barton’s removal in the first instance. Because the Court’s opinion does no justice to the [Immigration and Nationality Act], let alone to longtime LPRs like Barton, I respectfully dissent.

Read the full opinion below:

Barton v Barr by Law&Crime on Scribd

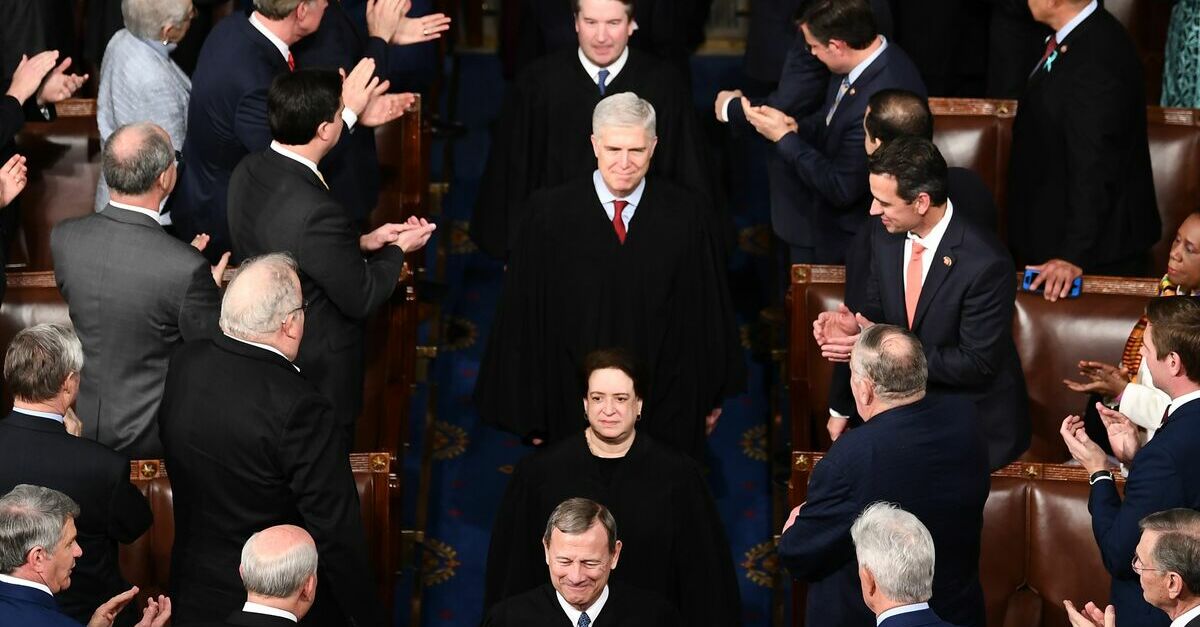

[image via BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images]