The U.S. Supreme Court, in a Justice Amy Coney Barrett-less 8-0 decision on Thursday, deciding that the people of faith can file suit under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA) against government officials who have “unlawfully burdened” their religious exercise. But those government officials will have a defense available to them that has often been criticized in the context of police misconduct: qualified immunity.

In Tanzin v. Tanvir, practicing Muslims alleged that they were placed on a No Fly List because they refused to act as FBI informants against their own religious community—resulting in lost job opportunities and money wasted on tickets for flights:

Respondents Muhammad Tanvir, Jameel Algibhah, and Naveed Shinwari are practicing Muslims who claim that Federal Bureau of Investigation agents placed them on the No Fly List in retaliation for their refusal to act as informants against their religious communities. Respondents sued various agents in their official capacities, seeking re- moval from the No Fly List. They also sued the agents in their individual capacities for money damages. According to respondents, the retaliation cost them substantial sums of money: airline tickets wasted and income from job opportunities lost.

More than a year after respondents sued, the Department of Homeland Security informed them that they could now fly, thus mooting the claims for injunctive relief. The District Court then dismissed the individual-capacity claims for money damages, ruling that RFRA does not permit monetary relief.

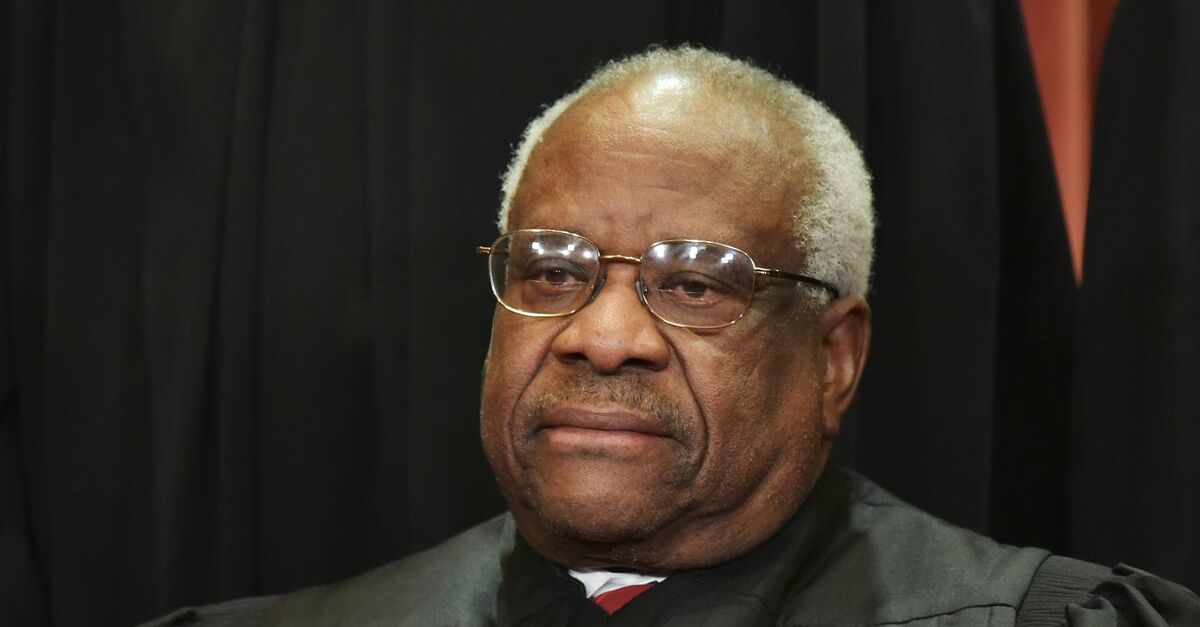

Justice Clarence Thomas penned the opinion of the unanimous court, finding that RFRA, which “prohibits the Federal Government from imposing substantial burdens on religious exercise, absent a compelling interest pursued through the least restrictive means” also gives a “person whose religious exercise has been unlawfully burdened the right to seek ‘appropriate relief.'”

The Supreme Court held that “claims for money damages” against government officials in their official individual capacities are included in what constitutes “appropriate relief.”

Justice Thomas noted that money damages are, in some cases, really the only remedy: “For certain injuries, such as respondents’ wasted plane tickets, effective relief consists of damages, not an injunction.”

“To be sure, there may be policy reasons why Congress may wish to shield Government employees from personal liability, and Congress is free to do so. But there are no constitutional reasons why we must do so in its stead,” the court concluded. “To the extent the Government asks us to create a new policy-based presumption against damages against individual officials, we are not at liberty to do so.”

Justice Thomas also added a footnote pointing out that both the government and the practicing Muslims alleging violations of their religious rights agreed that individual government officials accused of such misconduct are “entitled” to raising a qualified immunity defense:

Both the Government and respondents agree that government officials are entitled to assert a qualified immunity defense when sued in their individual capacities for money damages under RFRA. Indeed, respondents emphasize that the “qualified immunity defense was created for precisely these circumstances,” Brief for Respondents 22, and is a “powerful shield” that “protects all but the plainly incompetent or those who flout clearly established law,” Tr. of Oral Arg. 42; see District of Columbia v. Wesby, 583 U. S. ___, ___–___ (2018) (slip op., at 13–15).

[Image via MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images]