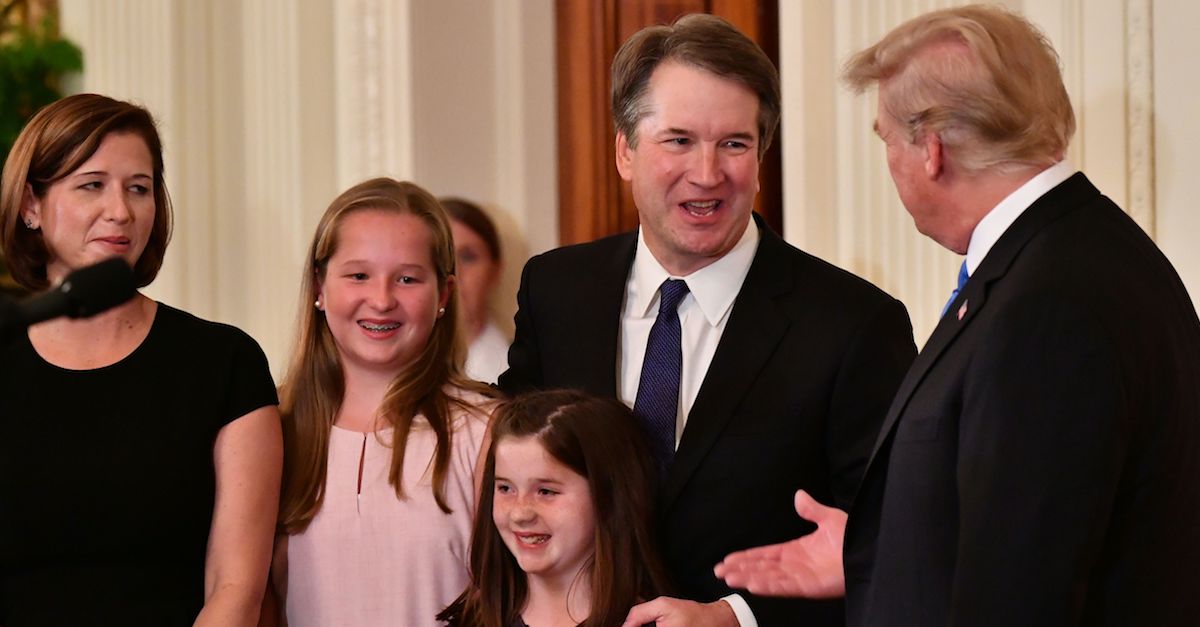

Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, his wife Ashley Estes Kavanaugh and their two daughters speak with US President Donald Trump after he announced his nomination in the East Room of the White House on July 9, 2018 in Washington, DC. (Photo by MANDEL NGAN / AFP) (Photo credit should read MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images)

According to Kavanaugh’s 2009 Minnesota Law Review article “Separation of Powers During the Forty-Fourth Presidency and Beyond,” he’d also probably say Trump should not have to even talk to special counsel Robert Mueller.

Kavanaugh wrote that his experience working in the White House under George W. Bush, and his experience investigating Bill Clinton on special prosecutor Kenneth Starr’s staff in the ’90s changed his views on what can be done to a sitting President.

“I believe that the President should be excused from some of the burdens of ordinary citizenship while serving in office,” he wrote. “This is not something I necessarily thought in the 1980s or 1990s. Like many Americans at that time, I believed that the President should be required to shoulder the same obligations that we all carry. But in retrospect, that seems a mistake.”

“Looking back to the late 1990s, for example, the nation certainly would have been better off if President Clinton could have focused on Osama bin Laden without being distracted by the Paula Jones sexual harassment case and its criminal investigation offshoots,” he said.

Kavanaugh proposed that Congress enact a statute deferring “any personal civil suits against presidents” while the president is in office, arguing that it is necessary so the president can “focus on the vital duties he was elected to perform.” He also said Congress should “consider doing the same” for criminal investigations and prosecutions of the president to avoid “crippling” the federal government.

Kavanaugh also believes that a President should be immune from criminal investigations. Consider this paragraph:

In particular, Congress might consider a law exempting a President—while in office—from criminal prosecution and investigation, including from questioning by criminal prosecutors or defense counsel [emphasis ours]. Criminal investigations targeted at or revolving around a President are inevitably politicized by both their supporters and critics. As I have written before, “no Attorney General or special counsel will have the necessary credibility to avoid the inevitable charges that he is politically motivated—whether in favor of the President or against him, depending on the individual leading the investigation and its results.” The indictment and trial of a sitting President, moreover, would cripple the federal government, rendering it unable to function with credibility in either the international or domestic arenas. Such an outcome would ill serve the public interest, especially in times of financial or national security crisis.

Kavanaugh’s reasoning was not to “put the President above the law” but to “defer litigation and investigations until the President is out of office.”

He also said that the impeachment process is there for a reason.

“[T]he Constitution already provides that check. If the President does something dastardly, the impeachment process is available,” he said.

Kavanaugh does have a history on the matter of impeachment in the form of a broad definition of obstruction of justice.

[Image via MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images]