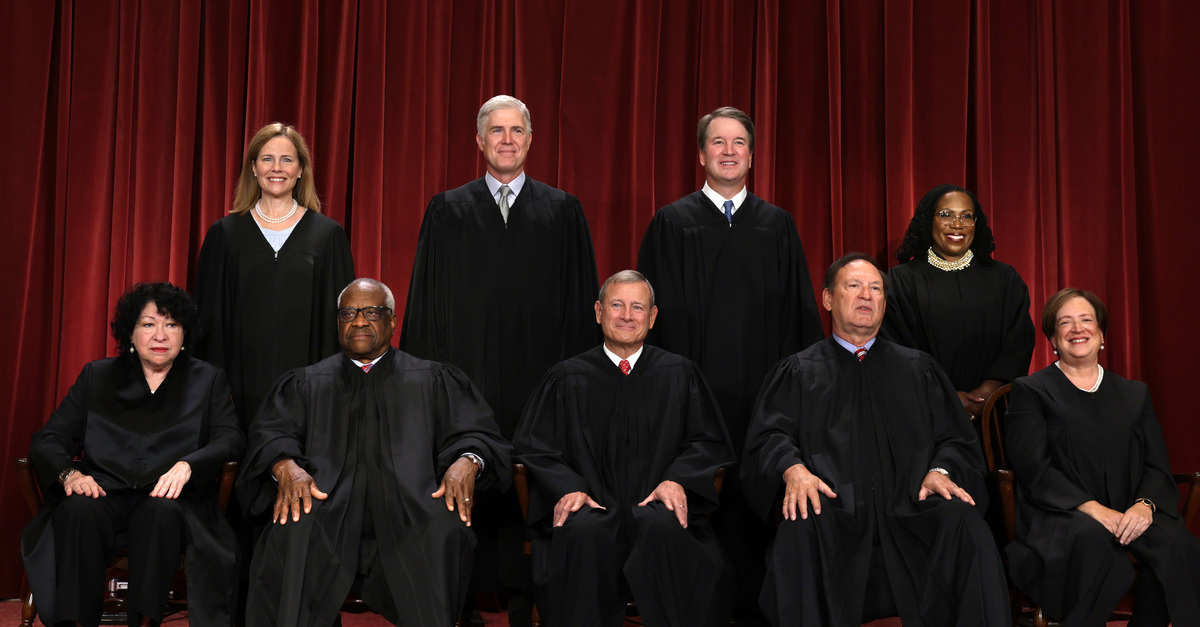

(Front row L-R) Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, Associate Justice Samuel Alito, and Associate Justice Elena Kagan, (back row L-R) Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson.

The justices heard oral arguments Tuesday in Mallory v. Norfolk Southern Railway Co., a case with potential to upend the framework typically applied to a foundational legal principle: personal jurisdiction over corporations.

Personal jurisdiction is the power of a particular court to bind specific parties to their decisions. In practical terms, plaintiffs must establish personal jurisdiction over each defendant in order to have their cases actually move forward against those defendants in the particular court in which the plaintiff filed.

Confusion often occurs when the defendant in question is a corporation instead of an individual. Currently, under an enormous and well-known body of federal law, a plaintiff is permitted to sue a company about any alleged wrongdoing in the state of the company’s incorporation or in the company’s principle state of business. In both instances, the court is said to have “general jurisdiction” over the corporate defendant.

The rules are more complex when a plaintiff seeks to sue a corporation in some other state. If the out-of-state defendant consents to participate in the lawsuit, there is no issue and the case can proceed. A non-consenting company, however, is only compelled to travel to an out-of-state forum to defend a lawsuit that is connected to contacts that company has with the forum state (this route to personal jurisdiction is known as “specific jurisdiction”).

Robert Mallory is a Virginia man who worked for Norfolk Southern Railway for 17 years in Virginia and Ohio. Mallory claims that he was exposed to asbestos and toxic chemicals during his employment, resulting in his having contracted colon cancer.

Although none of the facts related to Mallory’s tort claim occurred in Pennsylvania, Mallory sued the defendant railroad company in Pennsylvania. He argued that a Pennsylvania statute authorized personal jurisdiction over over Norfolk Southern based on the railroad’s being registered to do business in the Keystone State. Pennsylvania’s law gives Pennsylvania courts jurisdiction over any businesses registered in the state to do business.

The case presents what some of the justices called a “foreign cubed” situation: a lawsuit by a non-resident of a state against a non-resident corporation about an action that occurred outside the state. At stake is not just the fate of Mallory’s lawsuit, but the future of countless others that could be waged against corporations across the U.S.

The Biden administration filed an amicus brief siding with the railroad. The government’s position is that a ruling for Mallory threatens all foreign defendants with similar outcomes, and that such a reality has negative implications for foreign relations.

Because the case could change longstanding federal civil procedure jurisprudence, the justices raised concerns not only about a ruling’s potential effects, but also about how the Supreme Court’s decision could square with historical tenets of constitutional law — or as goes the phrase in civl procedure circles, “traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.”

Justice Clarence Thomas asked Mallory’s lawyer, former Anthony Kennedy clerk Ashley Keller, whether the Pennsylvania statute might be analogized to an an individual’s consent under the Fourth Amendment.

“So is there something that the railroad has that it’s giving up, or is it simply a sovereign and a corporation entering into an agreement in order for the corporation to do business in Pennsylvania?” asked Thomas.

Keller answered that the situation is not quite the same as a waiver of Fourth Amendment rights, and that the relationship between businesses and Pennsylvania could be understood as akin to parties to a contract.

When Keller argued that legal history and tradition support a ruling in his client’s favor, Chief Justice John Roberts remarked, “Well, history and tradition move on.” Roberts asked whether the precedents on which Keller based his argument had not already been “relegated to the dustbin of history.”

Justice Elena Kagan questioned the notion that a corporation’s registration in Pennsylvania could constitute consent to jurisdiction.

“Is there consent by doing business?” Kagan asked. “Isn’t it just alerting the state that they’re doing business?”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson framed the issue as one of individual rights.

“I think that this Court had determined that personal jurisdiction is an individual right, and that individual rights can be waived, and consent —as long as it is knowing and voluntary— is ordinarily the way people waive their individual rights,” the newest member of the nine said.

Justice Samuel Alito drew audible chuckles from his fellow justices when he asked, “Are there any natural persons who are present in all 50 states at the same time?” The question, though facetious, was likely meant to make the point that a ruling upholding the Pennsylvania statute could create a jurisdictional rule for corporations that goes far beyond the typical limitations placed on individual defendants.

Chief Justice Roberts pushed Keller on the implications of treating consent to personal jurisdiction as a prerequisite to doing business in Pennsylvania.

“The price of doing business in Pennsylvania is consenting to jurisdiction,” Roberts stated, before asking: “What if the price was $100,000?”

Justice Neil Gorsuch commented to the railroad’s counsel, Carter Phillips, that “if we are worried about fairness of consent and knowledge, there’s no doubt that the railroad understood by filing this paper, that it was subject to this law.”

When Phillips agreed, Gorsuch asked, “Why is it any less fair to treat corporations as consenting here if we treat individuals as subject to jurisdiction on a tag basis?” Gorsuch’s question about “tag jurisdiction” references the concept of subjecting an individual to personal jurisdiction simply by serving that person with process (thereby tagging them) while they are physically in a state.

“This does feel like a little bit of due process Lochnerism for corporations here, doesn’t it?” mused Gorsuch, referring to an era when the Supreme Court invalidated multiple laws that restricted business.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor was skeptical about Phillips’ argument that the Pennsylvania statute amounts to coercion and is, therefore, an inappropriate basis for establishing jurisdiction over his client.

“I can see where we might have a doctrine that says in an individual application there’s coercion, but I can’t see how we could say there is coercion for a company in your situation,” Sotomayor told Phillips.

Justice Jackson appeared to agree.

“You don’t have to do business in the state, you don’t have to come here,” Jackson said.

“[The jurisdiction clause] is a term in the agreement that we’re making with the businesses that come to our state,” Jackson summarized.

“It’s not as if we actually have a choice,” Phillips protested. Phillips went on to argue that because his client is a railroad, it is required to provide service in Pennsylvania, thereby forcing it to submit to jurisdiction whether or not it agrees.

The consequences of a ruling in Mallory’s favor would likely be far-reaching. Although the case concerns only Pennsylvania’s law, a ruling might well pave the way for similar statutes in other states. By contrast, a ruling in favor of the railroad would likely shield it — as well as other corporations — from lawsuits in Pennsylvania and elsewhere.

You can listen to the full oral arguments here.