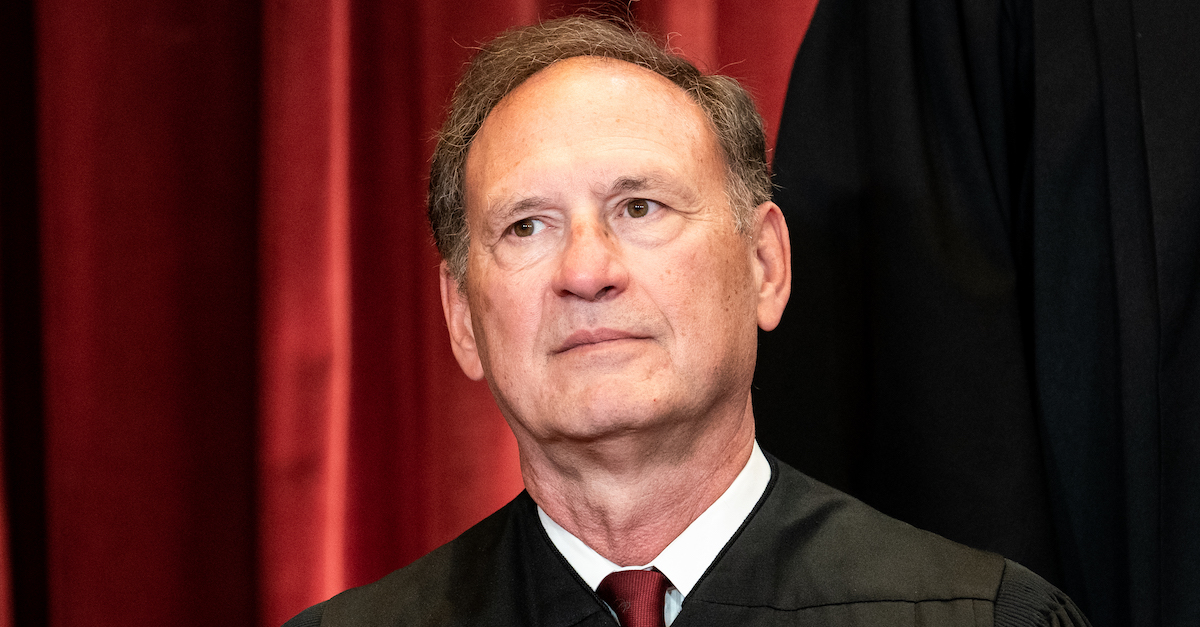

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Samuel Alito

A Seattle-based Christian group that refused to hire a bisexual attorney was denied a Supreme Court hearing on Monday, though two justices on the high court’s right flank were clearly receptive to the religious organization’s position.

In a six-page statement, Justice Samuel Alito pushed for a more expansive view of the so-called “ministerial exception” to federal anti-discrimination law. Joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, Alito’s statement in Seattle’s Union Gospel Mission v. Matthew S. Woods represents one in a series from Alito on giving religious groups latitude from civil rights law. All of the justices appeared to agree the case is not yet ripe for review.

The controversy behind the case began in 2017 when attorney Matthew Woods sued Union Gospel Mission (the “Mission”) in state court in Washington. Woods said the Christian group violated federal anti-discrimination law by refusing to hire him as a staff attorney with its Open Door Legal Services (ODLS) programs.

Celebrating his latest legal victim, Woods told Law&Crime in a statement: “I brought this case because I didn’t want my experience to happen to anyone else.”

ODLS is a free legal-aid clinic operated by the Mission — a nonprofit Christian ministry. The clinic is religious in nature and its staff conducts religious activities with its patrons, such as praying with them and discussing Jesus. The clinic requires that employees regularly attend church, receive a reference from a pastor, and provide information about their “personal relationship with Jesus.”

Woods was a former summer intern and volunteer with ODLS. When ODLS posted an open position for a staff attorney, Woods spoke to the director about applying. In response, the director told Woods that he was not “able to apply,” because the employee handbook explicitly forbade “homosexual behavior.” Woods applied anyway, and in his cover letter, asked ODLS to change its practices.

ODLS refused to change its policies, and the director explained to Woods that his “employment application was not viable because he did not comply with the Mission’s religious lifestyle requirements, did not actively attend church, and did not exhibit a passion for helping clients develop a personal relationship with Jesus.” Woods sued, alleging that the Mission discriminated against him based on his sexual orientation, which is illegal under the Washington State constitution.

“I volunteered with SUGM for several years and felt spiritually aligned there, only for SUGM to invalidate my ability to do that work with them just because of who I am and whom I love,” Woods wrote in a statement. “I’m grateful that LGBTQ+ people of faith like me will have more opportunities to work without discrimination now.”

Previously, the Washington State Supreme Court ruled in Woods’ favor, holding that discrimination based on sexual orientation does indeed violate the Washington State constitution. That court, however, was clear to point out that the discrimination was problematic because Woods would have been an employee. It elaborated, explaining that the state constitution would not have been offended if Woods’ position had been one of a “minister.” The court then remanded the case to “the trial court to determine whether staff attorneys can qualify as ministers.” The Supreme Court’s denial preserves that status quo.

Justice Alito echoed his rulings in recent cases involving the “ministerial exception” in schools, writing that the Washington Supreme Court was wrong to believe the exception applies only to “formal ministers.” Rather, he reminded, “our precedents suggest that the guarantee of church autonomy is not so narrowly confined.”

Quoting his own concurrence in a recent case, Alito wrote, that “religious groups’ ‘very existence is dedicated to the

collective expression and propagation of shared religious ideals,’ and ‘there can be no doubt that the messenger matters’ in that religious expression.'” Staff attorneys may well constitute “messengers” in this context, Alito wrote.

The justice then continued, warning against depriving religious institutions of their freedom to choose its own messengers:

To force religious organizations to hire messengers and other personnel who do not share their religious views would undermine not only the autonomy of many religious organizations but also their continued viability. If States could compel religious organizations to hire employees who fundamentally disagree with them, many religious non-profits would be extinguished from participation in public life—perhaps by those who disagree with their theological views most vigorously. Driving such organizations from the public square would not just infringe on their rights to freely exercise religion but would greatly impoverish our Nation’s civic and religious life.

Alito remarked that Woods’ case is one that “illustrates that serious risk,” and commented that the Washington Supreme Court may have ruled in a way directly in conflict with the United States Constitution.

The mission’s attorney John Bursch took Alito’s statement as an auspicious sign for the future of the litigation.

“Churches and religious organizations have the First Amendment right to hire those who share their beliefs without being punished by the government,” Bursch told Law&Crime in an email. “That’s why, even though the Supreme Court decided not to take this case yet, we are pleased to see the statement from some of the justices on the court saying that the ‘Washington Supreme Court’s decision may warrant our review in the future’ once the case reaches a later stage of litigation.”

Alito allowed that the case is not yet ready for SCOTUS review, writing that “threshold issues would make it difficult for us to review this case” at the current time.

Legal experts were quick to call out the conservative justices’ statement as an indication of their intent to expand the ministerial exception further. Slate‘s Mark Joseph Stern tweeted, “Alito, joined by Thomas, wants to expand religious employers’ “ministerial exception” from civil rights law, giving these employers total freedom to discriminate against any job applicant or employee who does not share the employer’s religious views.”

Alito, joined by Thomas, wants to expand religious employers’ “ministerial exception” from civil rights law, giving these employers total freedom to discriminate against any job applicant or employee who does not share the employer’s religious views. https://t.co/5DjHHwpJFm pic.twitter.com/tlMjdgVOHr

— Mark Joseph Stern (@mjs_DC) March 21, 2022

Zack Ford, the press secretary for the advocacy group Alliance for Justice, tweeted: “There’s no subtlety here. Alito and Thomas want employers to have free rein to discriminate against workers simply for being in a same-sex relationship if that violates the employer’s religious beliefs.”

There’s no subtlety here. Alito and Thomas want employers to have free rein to discriminate against workers simply for being in a same-sex relationship if that violates the employer’s religious beliefs.

Next year’s 303 Creative ruling is going to be so terrible. https://t.co/lHv5Y1MzXR

— Zack Ford (@ZackFord) March 21, 2022

Woods’ attorney Denise Diskin, the executive director of the QLaw Foundation of Washington, said in a statement: “Discrimination does not belong in social services, and we are excited to begin the process of confirming that LGBTQ+ people are just as qualified as anyone else to provide support and help to vulnerable people in their communities.”

Update—March 21 at 1:36 p.m. Eastern Time: This story has been updated to add comments by Woods and his attorney.

Read the statement, below:

[image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]