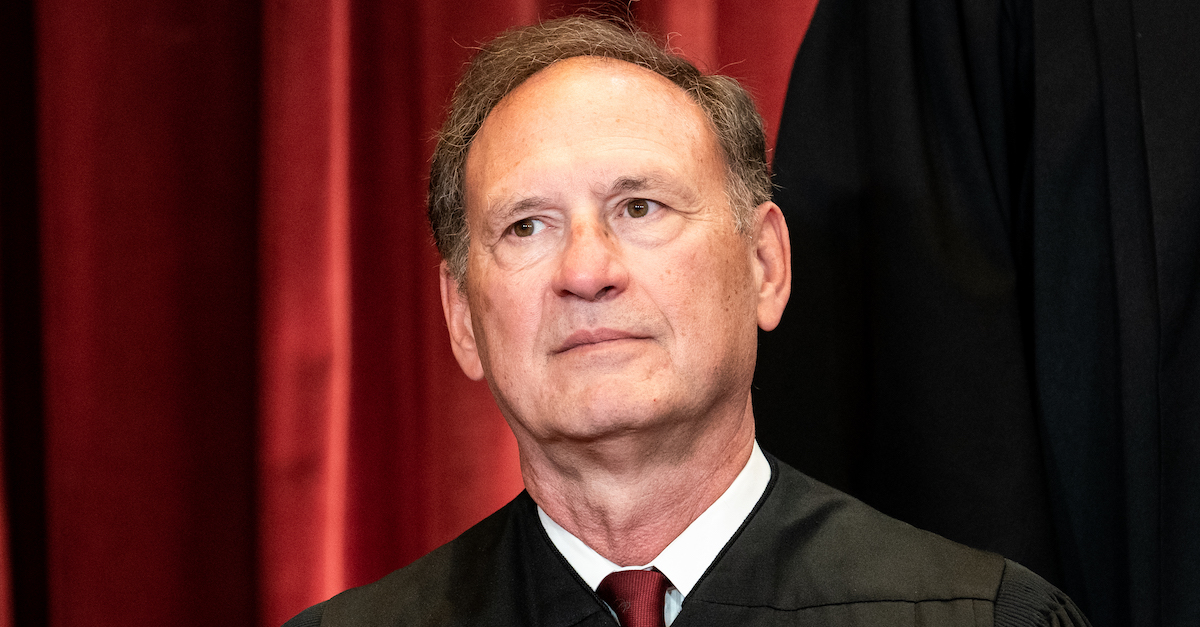

Associate Justice Samuel Alito sits during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021.

The Supreme Court of the United States on Monday declined to hear a would-be case between Texas and California–foregoing its original jurisdiction. Right-wing Justice Samuel Alito strongly disagreed with the decision to deny Texas leave to file the bill of complaint. In a 10-page dissent that mused about potential warfare between the Lone Star State and the Golden State over a still-simmering dispute, Alito upbraided his peers left and right for effectively leaving Texas high and dry.

This decision, the dissent says, leaves Texas “without any judicial forum.” The majority clearly doesn’t see an issue there.

The basic issue is a 2016 California law that prohibits the state from spending any money on travel to other states that don’t offer adequate protections for LGBTQ individuals–as enumerated in the law itself. Texas alleged various constitutional violations and argued for the exercise of original jurisdiction in an effort to have the nation’s high court weigh in. But at least five justices decided against allowing Texas to even file a formal complaint over the law.

The threat of war was actually raised in Texas’s failed effort.

The dissent notes:

In seeking to file its complaint, Texas argues that this is precisely the type of dispute for which our exclusive original jurisdiction was designed. Texas writes that “the model case for [the] invocation of [our] original jurisdiction is a dispute between States of such seriousness that it would amount to casus belli if the States were fully sovereign.”

The term casus belli is international relations jargon that translates into a state’s justification for war. In other words, Texas argued before the court that if they were an actual country they might just have a valid reason to subject California to a military campaign against pro-LGBTQ legislation.

The full court rejected that line of thought. But Alito, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, embraced the notion.

“Texas notes that economic sanctions have often roiled international relations and have sometimes led to war,” Alito continued. “And Texas reminds us that the Founders were well aware of the danger of economic warfare between States.”

The dissent offered a terse history lesson to support Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s ultimately unpersuasive comparative efforts:

The Republic of Texas was an independent nation for 10 years (1836–1846), and the California Republic claimed a similar status for a brief time in 1846. If they were independent nations today, it is entirely possible that their dispute would be the source of considerable international tension. As sovereign nations, they might resolve their dispute by diplomacy, by submitting it to international arbitration, or by self-help measures. When they entered the Union, these two behemoths relinquished the full measure of sovereign power that they once possessed, but they acquired the right to have their disputes with other States adjudicated by the Nation’s highest court.

“The Court now denies Texas that right,” Alito went on. “It will not even permit the filing of Texas’s bill of complaint. This understanding of our exclusive original jurisdiction should be reexamined.”

A lengthier historical treatise was attempted in an effort to catalogue what Alito and Thomas call the “questionable” 45-plus-year tradition of refusing to permit most state vs. state disputes from being briefed and argued before the nation’s high court.

“[T]hat is especially true when, as in this case, our original jurisdictional is exclusive,” Alito argued before invoking the history. “The principal reason provided—that entertaining all suits between two States would crowd out consideration of more important matters on our appellate docket—rests on a dubious factual premise.”

The Supreme Court, the dissent noted, was previously far more inclined to entertain such disputes but that all changed in 1976 in the case stylized as Arizona v. New Mexico “where, for the first time, the Court declined to exercise its exclusive jurisdiction in a controversy between two States.”

And the justices haven’t really looked back since then. Alito and Thomas would rather the court do exactly the opposite.

Their dissent opened with a hypothetical “federal district court” judge who declines to allow a Texan to sue a Californian over a traffic accident.

“Can we justify our refusal to entertain Texas’s suit on essentially the same ground that we would reject out of hand in the hypothetical diversity case just described, that is, on the ground that our original jurisdiction no longer seems as important as it was when the Constitution was adopted, and that a proliferation of original cases would crowd out more important matters on our appellate docket?” Alito asked.

The court’s majority answered: Yes.

You may recall that Alito and Thomas were the only justices who thought the court had no choice but to grant Paxton leave to file a bill of complaint to overturn the 2020 election. The majority denied that leave as well.

[image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]