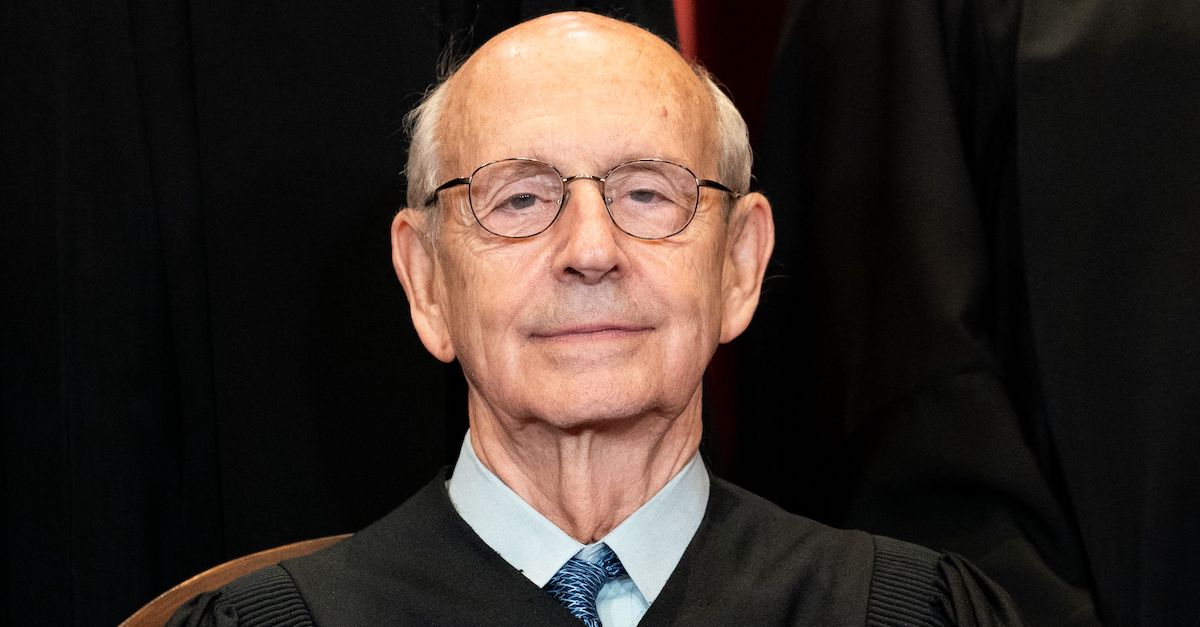

Associate Justice Stephen Breyer sits during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021.

Justice Stephen Breyer participated in the final oral argument of his Supreme Court career on Wednesday as the high court considered Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta. The case presents the impactful question of whether individual states have the authority to prosecute major crimes committed on Indian land by Indian perpetrators against non-Indian victims.

The State of Oklahoma argues that it should have jurisdiction to prosecute such crimes not only because it should be allowed to protect its citizens, but also because the federal government is seriously shirking its responsibility to take on these cases.

During the two hours of oral argument, several justices indicated that they would vote just as they had in the 2020 case McGirt v. Oklahoma. The Castro-Huerta case is essentially a sequel to the Court’s 5-4 decision in McGirt, in which the Court ruled that 40% of Oklahoma’s land remains a Native American reservation. The Neil Gorsuch-led majority reasoned that because Congress never disestablished the Native American reservation, that land is considered “Indian Country.” In McGirt, Gorsuch, the sole justice hailing from the Western U.S., joined the Court’s liberal wing (which included the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg) to side with the Indian tribes.

A ruling against Oklahoma in the Castro-Huerta case would mean that the state conviction of Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta for criminal neglect of his 5-year-old stepdaughter would be overturned. Castro-Huerta is not a Native American, but his stepdaughter is a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and the crime was committed on Indian land.

Justice Gorsuch dominated the early questioning of attorney Kannon Shanmugam who argued on Oklahoma’s behalf. The justice was overtly skeptical of Oklahoma’s position. Gorusch reminded Shanmugam of historical context while probing him about the interests to be balanced.

“We have the treaties,” said Gorsuch, “which have been in existence and promising this tribe since since before the Trail of Tears they would not be subjected to state jurisdiction precisely because the states were known to be their enemies.”

Shanmugam responded, “Of course the tribes have an interest in protecting their members from criminal offenses,” and continued, “Oklahoma likewise has an interest in protecting all of its citizens, including its tribal citizens, who, in Oklahoma have been citizens of the state longer than anywhere else in the nation.”

“The history and the reality should stare us all in the face,” Gorsuch said later, elaborating to explain that tribes would resist state jurisdiction because of the history of bias against Native Americans.

Shanmugam responded and called the law enforcement issues in play “very real,” and arguing that there are “whole categories of crimes going unprosecuted due to lack of federal law enforcement resources.

Justice Breyer suggested that the proper remedy for such a shortfall could be achieved with a targeted request from local congressional representatives. Breyer continued to note that if SCOTUS sides with Oklahoma in this case, it could overturn what has been a longstanding norm in all 50 states.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor offered something of a different perspective as to the true interests of Indian tribes, and suggested that the tribes may have due process about allowing states to have concurrent jurisdiction with the federal government. Sotomayor also suggested that Oklahoma’s statistics may be inflated.

“There’s an article in the Atlantic that suggests that your figures are grossly exaggerated,” Sotomayor noted.

Shanmugam responded that more accurate statistics are contained in a recent Wall Street Journal article, but argued that the Court should avoid deciding the case based on media coverage.

Justice Elena Kagan appeared completely unconvinced by Oklahoma’s position. When Shanmugam argued that precedent exists to support his client’s argument, Kagan shot back, “I don’t know if you get to talk about precedent,” and commented, “six times, we have said the exact opposite of your position.” Kagan argued the Supreme Court not only indicated multiple times that Oklahoma is wrong, but also that Congress and the executive branch has repeatedly done so, too.

“You’re asking us to do a big lift on the basis of language that as I say seems to me more naturally read against you,” Kagan responded to Shanmugan’s contention that the applicable statute should be read in his favor.

Chief Justice John Roberts asked whether the McGirt case offers any guidance that would assist the Court in analyzing the issue at hand. Shanmugam responded that it did not, but commented that he was at a loss to understand why the federal government was arguing for exclusive jurisdiction in a context in which it is already “failing at the task” of adequately prosecuting the relevant cases.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh was overtly receptive to Oklahoma’s argument, and summarized it by saying,”Indian victims right now are not being protected because the federal government doesn’t have the resources to prosecute all these crimes.” Granting Oklahoma concurrent jurisdiction, argued Kavanaugh, “would not be displacing the federal government,” but would simply be providing “additional prosecutors to protect Indian victims against non-Indians.”

“Ruling against you will hurt Indian victims,” Kavanaugh told Shanmugam.

When attorney Zachary Schauf took the podium to argue for Castro-Huerta, he told the justices that in the case before them, the victim’s family had consented to his client’s sentence specifically because it would be carried out in federal prison. Shauf said the family had a “pretty significant interest” in avoiding Oklahoma’s more lenient rules on parole.

Deputy Solicitor General for the Department of Justice Edwin Kneedler argued on behalf of the Biden Administration as an amicus curiae, and supporting Castro-Huerta.

Justice Samuel Alito asked Kneedler to explain why exclusive federal jurisdiction would be better than concurrent federal and state jurisdiction. Kneedler responded that exclusive federal jurisdiction would not necessarily disadvantage any particular Indian victim, but that his position takes into account the interests of three independent sovereigns: the federal and state governments, and the Indian tribe.

“This sounds awfully abstract,” commented Alito. The colloquy then evolved into a discussion about the current state of affairs in Oklahoma.

“Can you give me an assessment of Oklahoma right now?” asked Alito. “Are the criminal laws being adequately enforced right now?” Alito continued his question at length, asking whether the federal government has enough federal agents, prosecutors, judges, and court staff to properly carry out the necessary prosecutions.

“I’m not here to minimize the challenge that has resulted from the decision in McGirt,” Kneedler answered—before explaining that resources have been provided to support federal prosecutorial efforts in the region.

“Is it adequate from the perspective of the United States?” asked Alito. “Is it sustainable?”

Kneedler responded that the administration has requested $40 million in funding and that Congress, “in its political responsibility, we trust, will appropriate that money.”

At the conclusion of oral arguments, Chief Justice Roberts noted for the record that the case was the 150th time Kneedler presented oral arguments before the Supreme Court. “On behalf of the Court, thank you for your skilled advocacy over the years,” Roberts said.

The morning’s arguments ended on an emotional note as Roberts pointed out that the proceedings marked the final time Justice Breyer would participate in oral arguments.

“For 28 years, this has been his arena for remarks profound and moving, questions challenging and insightful, and hypotheticals downright silly,” Roberts said, choking up. “This sitting alone has brought us radioactive muskrats and John the Tigerman” — references that drew laughs from the crowd.

Roberts’ voice trembled again as he said that the high court would read formal letters into the record regarding Breyer’s retirement, but “for now, we leave the courtroom with deep appreciation for the privilege of sharing this bench with him.”

You can listen to the full oral arguments here.

Carly Atchison, communications director for Oklahoma Governor J. Kevin Stitt (R), provided the following statement on the case to Law&Crime via email:

Governor Stitt believes that the State should be able to protect all Oklahomans, regardless of race, and no criminal should go unpunished. Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta is a callous child abuser who so severely neglected his five-year-old Indian stepdaughter, who has cerebral palsy and is legally blind, that when she was mercifully rushed to the emergency room she was dehydrated, emaciated, covered in lice and excrement, and weighed just nineteen pounds. Castro-Huerta should not be given any chance to get off easy for this crime and the state will argue that it has the right to protect Indian victims in front of the Supreme Court today.

[image via Erin Schaff/pool/AFP via Getty Images]