The Supreme Court on Friday overturned the highly publicized murder conviction of Curtis Flowers, in a 7-2 decision finding that the Mississippi district attorney Doug Evans had intentionally struck potential African American jurors from serving on the case. While the decision was a victory for racial justice in the legal system, Justice Clarence Thomas, the lone African American member of the court, contributed a scathing dissent and suggested that racial discrimination in the jury selection process should not be regulated.

The dispute centered around the jury selection process in criminal cases, specifically, “peremptory challenges,” which allow attorneys to freely dismiss a predetermined number of potential jurors at their discretion for any non-discriminatory reason. The validity of a peremptory challenge may be objected to on grounds that the juror was dismissed based on their race, sex, or ethnicity in what is known as a Batson challenge, from the court’s 1986 case Batson v. Kentucky.

In Flowers’s first four trials between 1997 and 2007, Evans used all 36 of his peremptory challenges to prevent potential black jurors from being seated on the jury. Three of those trials ended in convictions that were reversed on appeal while one resulted in a mistrial.

As noted in Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s majority opinion, the evidence of procedural discrimination permeated the jury selection processes throughout Curtis Flowers’ six criminal trials, tainting the objective fairness of the verdicts rendered against him. Even Justice Samuel Alito, renowned for his deference to prosecutorial power, joined Kavanaugh’s opinion, noting that the case was “highly unusual” and “likely one of a kind.”

“[T]he State employed its peremptory challenges to strike 41 of the 42 black prospective jurors that it could have struck,” Kavanaugh wrote.

“The State asked the five black prospective jurors who were struck a total of 145 questions,” Kavanaugh continued, adding that, “By contrast, the State asked the 11 seated white jurors a total of 12 questions. ”

Thomas staunchly disagreed with Kavanaugh’s reasoning, arguing that “disparate questioning” such as this merely reflects “ordinary race-neutral considerations,” not evidence of discriminatory intent.

“The majority ominously warns that, through questioning, prosecutors ‘can try to find some pretextual reason…to justify what is in reality a racially motivated strike’ and that ‘[p]rosecutors can decline to seek what they do not want to find about white prospective jurors.’ I would not so blithely impute single-minded racism to others. Doing so cheapens actual cases of discrimination,” he wrote in response.

But Thomas doesn’t just disagree with the majority ruling that prosecutors unconstitutionally struck potential jurors based on their race – he disagrees with Batson altogether.

“The more fundamental problem is Batson itself. The ‘entire line of cases following Batson’ is ‘a misguided effort to remedy a general societal wrong by using the Constitution to regulate the traditionally discretionary exercise of peremptory challenges,’” Thomas wrote, adding that “black criminal defendants will rue the day that this Court ventured down this road that inexorably will lead to the elimination of peremptory strikes.”

Thomas went on to point out that Curtis Flowers can stand trial for a seventh time and be convicted again.

“Today’s decision distorts the record of this case, eviscerates our standard of review, and vacates four murder convictions because the state struck a juror who would have been stricken by any competent attorney,” Thomas said, latter adding the following: “If the Court’s opinion today has a redeeming quality, it is this: The State is perfectly free to convict Curtis Flowers again.”

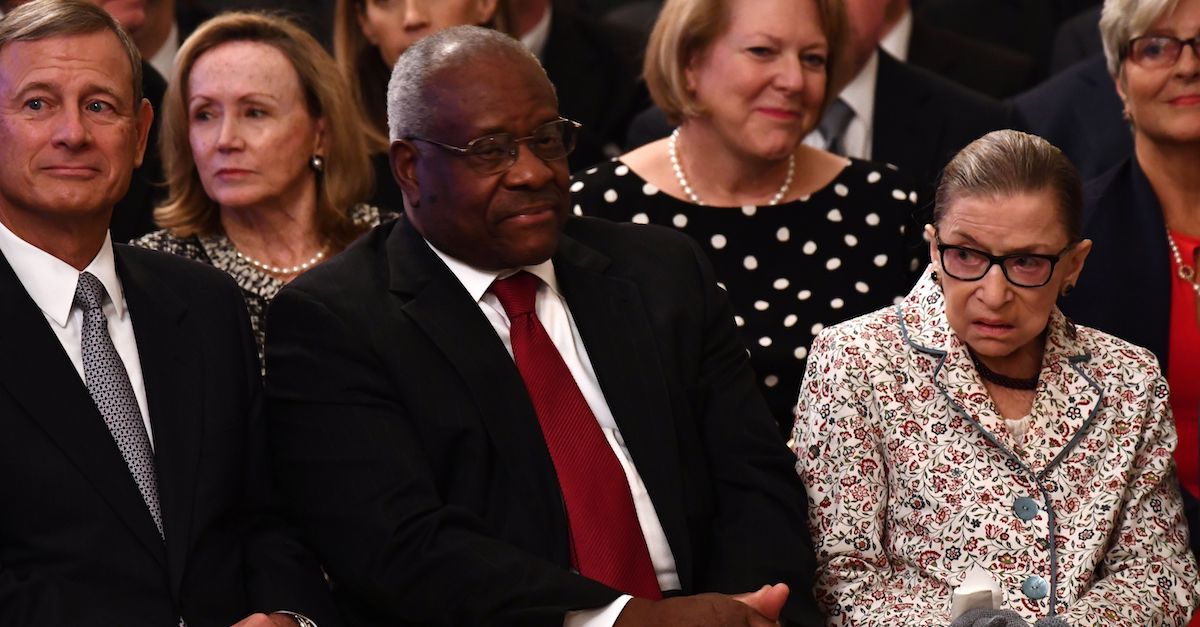

[Image via BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP/Getty Images]