President Donald Trump has pledged to “open up” the nation’s libel laws so he can sue the media and “win lots of money.”

President Donald Trump has pledged to “open up” the nation’s libel laws so he can sue the media and “win lots of money.”

But Trump’s top three picks for the Supreme Court appear unlikely to destroy the well-established First Amendment protections for the media and free expression, at least based on their court decisions.

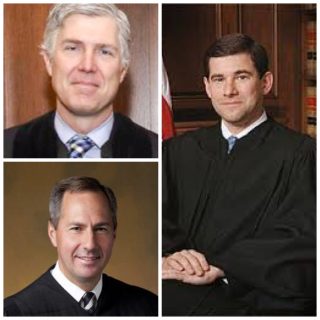

The three finalists – federal appellate court judges Neil Gorsuch, Tom Hardiman, and William Pryor – all have written decisions or joined decisions applying mainstream legal rules protecting the media and businesses under the First Amendment

Here is a look at some media and free expression decisions by the three judges:

Judge Gorsuch, a Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals judge and reportedly Trump’s favorite pick, has applied the substantial truth rule to protect a television network.

In Bustos v. A & E Networks, Judge Gorsuch wrote the majority opinion dismissing a prisoner’s claim that A&E Networks falsely implied that the prisoner was member of Aryan Brotherhood, a white supremacist prison gang and criminal enterprise.

Judge Gorsuch ruled that even if the prisoner was technically right that he was not a member of the Aryan Brotherhood, the broadcast was protected by the substantial truth doctrine because the prisoner was associate of that gang and a gang co-conspirator, which is essentially the same – as far as the broader audience is concerned – to being a member of the gang.

Judge Gorsuch also joined a majority opinion in Alvarado v. KOB-TV, which dismissed claims by two undercover cops against a local TV station. The police officers claimed that the station reported that they were under investigation for sexual assault and revealed their identities, which they claimed was a wrongful publication of private facts and infliction of emotional distress.

The Tenth Circuit held that the news report about the sexual assault investigation was a matter of public concern, which trumped the officers’ privacy and emotional distress claims.

Judge Hardiman, who is a judge on the Third Circuit Court of Appeals and being pushed by his Third Circuit colleague and President Trump’s sister, Judge Maryanne Trump, has come down on the side of a newspaper in one case.

In 2013, Judge Hardiman joined a Third Circuit ruling that dismissed a libel lawsuit brought by a fellow judge who was as a retired local Virgin Islands judge. The Virgin Islands judge actually won his libel lawsuit against the Virgin Islands Daily News and the jury had awarded him $240,000.

The Third Circuit panel ruled that the jury got it wrong on actual malice and dismissed the judge’s entire case.

In Kendall v. Daily News Publishing, the Virgin Islands judge sued over newspaper reports about his decision allow an assault defendant to go free on his own recognizance, only to learn that the defendant murdered a 12-year-old girl weeks later, and his decision to allow a man convicted of rape to spend a weekend at his home before going to prison, and the man became involved in a stand-off with police that weekend.

The Virgin Islands judge did not sue over the words of the reports, but claimed that they carried hidden “implications” that were false.

The Third Circuit, joined by Judge Hardiman, ruled that the judge failed to show that the newspaper published the supposed implications with actual standard – publishing intending to convey the false implications or knowing the implications were likely –and tossed out the jury verdict and the judge’s case.

Trump has seen a few of his own libel cases dismissed because he failed to prove actual malice.

Judge Hardiman also wrote a 2010 Third Circuit decision dismissing a First Amendment claim against a police officer who arrested a man for filming the officer during an arrest.

The Third Circuit judge did not say that the man lacked a First Amendment right to film the officer, as some have incorrectly reported. Instead, Hardiman ruled that the law was not clear at the time of the arrest and therefore the officer could not be sued for the arrest on First Amendment grounds.

Judge Hardiman, however, acknowledged in that case, Kelly v. Borough of Carlisle, that some courts have recognized a “broad right to videotape police” under the First Amendment, especially for the purpose of reporting about the arrest to the public.

Judge Pryor, an Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals judge, has applied First Amendment protections in a taboo case and a libel case.

He joined a 2015 ruling where the circuit court held for the first time that “tatooing is an artistic expression protected by the First Amendment.”

In that case, Buerle v. City of Key West, the City of Key West argued that it needed to limit tatoo parlors to protect “rash” and “inebriated tourists” from getting ugly tatoos that they might later regret and stop spending tourists dollars in Key West.

The city even quoted the Jimmy Buffet song “Margaritaville” to make its point about tourists regretting their drunkenly obtained tatoos. The Tenth Circuit had a bit of fun with “Margaritaville,” noting that the song did not support the city at all, and in fact “the singer in ‘Margaritaville’ — seemingly far from suffering embarrassment over his tattoo — considers it ‘a real beauty.’”

Judge Pryor also joined a panel of judges in dismissing libel claims by Larry Klayman, who founded the conservative legal group Judicial Watch and, either with the group of as an individual, has filed at least two dozen lawsuits against the Clinton and Obama administrations, brought dozens of other political lawsuits, and convened a “citizens grand jury” to “indict” President Obama for supposedly forging his birth certificate to become president.

In that case, Klayman v. City Pages, the Eleventh Circuit held that Klayman was a public figure who could not establish that the Phoenix New Times and Voice Media published news reports about Klayman’s custody battle with actual malice, and his claims therefore must be dismissed.

The court also rejected Klayman’s argument that the district judge was biased against him because the judge quoted from the Lewis Caroll book Alice in Wonderland, including this quotation: “I’ve been considering words that start with the letter M. Moron. Mutiny. Murder. Mmm—malice.”

Klayman alleged that the judge’s quotation “implied that [Klayman] was the moron and thus demonstrated bias.”

The Eleventh Circuit panel, however, concluded that “the use of a literary device to enliven a summary judgment order does not evidence the kind of ‘deep seated favoritism or antagonism that would make fair judgment impossible.’”