The Department of Justice went to bat for President Donald Trump’s tax returns in amicus briefs submitted to the Supreme Court on Monday.

U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco’s briefs in support of Trump were filed in Trump v. Mazars USA, LLP, Trump v. Deutsche Bank AG and Trump v. Cyrus Vance. The DOJ’s Mazars and Deutsche Bank briefs were combined into one because they address the same question: “Whether Articles I and II of the United States Constitution allowed three committees of the House of Representatives to issue four subpoenas to third-party custodians for the personal financial records of the sitting President of the United States.”

The DOJ’s Trump v. Vance brief addresses the question of whether “Article II and the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution allowed a state grand jury to issue the subpoena here to a third-party custodian for the personal financial records of the sitting President of the United States.”

The Vance case is so named because Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance has sought to obtain President Trump’s tax returns as part of a criminal investigation of the Trump Organization. The Mazars case has to do with a congressional subpoena of Mazars USA, Trump’s finance firm. Democrats on the House Oversight Committee in April 2019 demanded multiple years of Trump’s tax documents for the purported purpose of providing insight as to whether current government ethics laws need to be updated. The Deutsche Bank case involves subpoenas issued by the House Intelligence and Financial Services Committees.

The Supreme Court consolidated the cases and set arguments for March 31, meaning that a decision is expected to come down in the months before the 2020 election.

The DOJ’s stated interest in the all of these cases: “The United States has a substantial interest in safeguarding the prerogatives of the Office of the President.”

A principal argument against the Mazars and Deutsche Bank subpoenas? They violate the Constitution because the congressional committees have neither demonstrated a legitimate legislative purpose nor the “need for the information sought”:

Article II provides an immunity from any process that would risk impairing the independence of his office or interfering with the performance of its functions. That risk is particularly palpable when the President’s political adversaries control one or both chambers of Congress. For that reason, the Framers deliberately sought to insulate the President from congressional interference in particular.

[…]

These cases involve the first attempts by congressional committees to demand the personal records of a sitting President of the United States. That use of their limited and implied investigatory powers poses a serious risk of harassing the President and distracting him from his constitutional duties. Article II and the separation of powers protect the Office of the President from such interference. Congressional committees that subpoena the President’s information must therefore make a heightened showing, both of a legitimate legislative purpose for the subpoenas and of the need for the information sought. Because the committees here did not make those showings, the subpoenas violate the Constitution.

DOJ argues that the congressional subpoenas, if validated by SCOTUS as legitimate, will have lasting implications for the separation of powers and open the door to political weaponization of subpoenas against presidents.

A principal argument against Vance’s state grand-jury subpoena? If the lower court’s decision is allowed to stand, this poses “serious risk” of states harassing and distracting presidents from from carrying out their constitutional duties:

State grand-jury subpoenas for a sitting President’s personal records pose serious risks to the independent functioning of the Office of the President. State prosecutors could use such subpoenas to harass the President in retaliation for the President’s official policies. Such subpoenas could also subject the President to significant burdens, threatening to divert the President’s time and energy from his singularly important public duties.

The structural features of state criminal justice systems heighten those dangers. Local prosecutors, who represent local electorates, have strong incentives to respond to the interests of their own communities, but no comparable incentives to consider the effects of their subpoenas on the Nation as a whole. And unlike federal prosecutors, local prosecutors are not subject to the centralized supervision of the Attorney General. Allowing state grand-jury subpoenas for the President’s personal records thus opens the door for communities to use such subpoenas to register their disapproval of the President’s policies.

If you really, really want to you can read both briefs below.

DOJ’s Mazars amicus brief by Law&Crime on Scribd

DOJ’s Trump v. Vance amicus brief by Law&Crime on Scribd

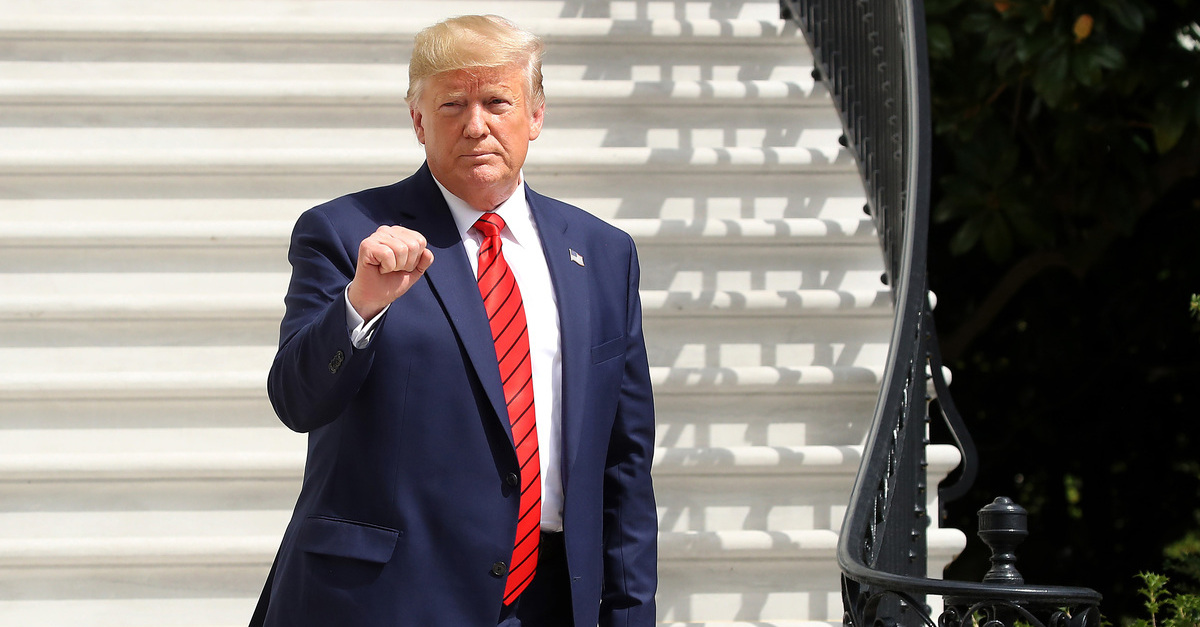

[Image via Mark Wilson/Getty Images]