The dust has begun to settle on the Kyle Rittenhouse not guilty verdict in Kenosha. The prosecution now seems much more complicated. The racial aspect of what had actually motivated Rittenhouse’s presence and shootings in Kenosha seems far less clear. Maybe, at bottom, it didn’t really figure so broadly except for the public sentiment – understandable obsession — about race. Hard to know.

Kyle Rittenhouse has now claimed, though — to Tucker Carlson, no less — that President Biden had “defamed” him over the killings. Should we really care? After all, didn’t Rittenhouse get away with killing two people in Kenosha (even though he was actually acquitted of murder)? What’s wrong with a president, particularly in a case involving the continuing national divide over race energized by a cross-racial police shooting, calling out in real time what he sees as endemic wrongdoing?

Now, in fairness to Biden, early in the development of the Kenosha story in August 2020, when he more than suggested that Rittenhouse was a white supremacist/militia member who crossed state lines to engage in mayhem, Biden was a presidential candidate, not a sitting president. Still, Biden’s electoral status shouldn’t matter. As a candidate in a battle for the hearts and minds of America, even without holding the status of president, his voice clearly had an inordinate capacity to influence the potential jury pool that would ultimately sit on the Rittenhouse case. Put a different way, didn’t he have the ability only equaled by one other person in America at the time to fan the flames in a particular direction? Trump, when Rittenhouse was charged, indeed, defended him saying “I guess he was in very big trouble. He probably would have been killed.”

Clearly, as at least I see it, influencing the jury pool was the last thing on Biden’s mind at the time of the killings, even though he surely knows better. As former chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Biden would instinctively have known how his comments, which appeared not simply in a passing moment, but also in a campaign video, might potentially impact a defendant’s right to a fair trial even when – maybe, especially when — the defendant is an out of state 18-year-old who claims self-defense after bringing an AR-15 to the party.

This kind of conduct by a person with the presidency on his mind isn’t sui generis, though. Famously, in early 1970 President Richard Nixon was grappling with the Vietnam War when Charles Manson and his coterie were on trial in Los Angeles for the horrendously bloody Tate-LaBianca murders. Apparently irritated that the press was so fixated on Manson, Nixon told reporters that although Manson was being portrayed by the press as a “very glamorous figure,” in reality he was “guilty, directly or indirectly, of eight murders without reason.” That is, the sitting President was publicly saying that Manson was “guilty” as charged while his trial was actually underway. Nixon’s comment spread across the media like wildfire (and this was long before the Internet). Defense counsel made motions for a mistrial, which were denied. But still: Nixon, an accomplished lawyer, knew better, just like Biden.

Sure, Nixon’s conduct was vastly different from Biden’s. In some ways, more offensive. In some ways less. Nixon’s (perhaps Machiavellian) comment had no practical or immediate value. Yes, Nixon was a “law and order” president, but his comment wasn’t promoting law and order – it seems to have simply been a politically reflexive act. The Manson case was really a one-off.

Biden, though, was actively running on a “political” campaign platform intent on ameliorating the racial divide in America and, presumably, he deliberately employed the Kenosha killings to try to ease it. But at what cost? Yes, some will argue, his remarks ultimately didn’t prejudice the jury. After all, the jury acquitted Rittenhouse across the board. Still, his comments might have seeped into the deep recesses of the minds of the pool from which a jury would be selected. We’ll never really know for sure, but it’s hardly a case of no harm, no foul.

While this piece is not about the politics involved, interestingly, pre-election Biden was less accusatory in relation to the Ahmaud Arbery killing (though he did comment last week about the guilty verdicts against Arbery’s convicted murderers, even as a federal hate crime prosecution remains pending). Biden previously tweeted that Arbery was “killed in cold blood,” without, however, accusing anyone in particular by name. President Trump, ironically, was far more balanced; he lamented the “heartbreaking” and “very, very disturbing” killing. Who knows what motivated Trump?

It has, parenthetically, become the practice of American prosecutors that their press releases announcing indictments note, in their last paragraph, that an indictment is not a conviction and that the defendant is presumed not guilty. Nice; but it’s taken on the quality of “boilerplate” language and is never repeated to the public by the media reporting the release or covering the prosecutor’s press conference.

Beyond that, though — and putting aside the 18-year-old Rittenhouse allowing himself, maybe offering himself, to be used as a political football by the political right — high ranking public officials, such as presidents or presidential candidates, need to stand down, aside from uttering the called-for platitude that “a thorough investigation and no holds barred prosecution is needed,” if they are asked about a pending criminal case. That is, until a verdict is reached – up or down.

Biden did tell the nation in response to Rittenhouse’s acquittal that although, like many Americans, he was left “angry and concerned” they should “respect the verdict.” Simply insufficient, however. While it wasn’t improper to express disappointment in the outcome, Biden’s transgression occurred immediately after the killings themselves. He should simply have said right at the outset: “Respect the process.”

The Rittenhouse trial is over and he can no longer be prejudiced – unless the Justice Department, as is unlikely, institutes federal charges against him. The politics over it, though, will invariably continue ferociously. Rittenhouse was awarded an “audience” with Trump at Mar-a-Lago, for example. And Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene has actually introduced a bill to award Congress’s highest honor to Rittenhouse. Surely, this Congress will do no such thing – he deserves no award — and won’t need President Biden’s public input to defeat such a bill. Moreover, President Biden has probably learned his lesson about Rittenhouse, and will likely say no more about it.

Yes, every president does have a bully pulpit and often should and must comment on public events, particularly when they relate to vital aspects of his presidential goals — addressing the race divide, among them. Trying to “bully” the Congress to pass legislation is, frankly, an important arrow in the president’s quiver. Employing the bully pulpit, however, in ways that might potentially “bully” action in the courts is radically different and flatly imprudent. Every president, on both sides of the political divide in America, needs to get behind that – strongly and unhesitatingly.

Just imagine awaiting trial on a criminal charge when the president or a popular presidential candidate has already effectively announced publicly, for whatever reason, that you’re guilty as charged! Would anyone want a jury even partly composed of admirers of a president (or presidential candidate) who has graphically spoken out against him deciding his fate?

It is one thing for media commentators – left, right or center — to opine on the guilt or innocence of a defendant before his trial is over. While such commentary is not ideal, such speech is a First Amendment-protected right nonetheless. It’s quite another thing for a president or presidential candidate publicly offering their opinion as to guilt before a verdict is reached. Persons holding powerful public office of course have First Amendment rights, but they also hold positions of public trust and duty to their fellow citizens, including preserving the right of their fellow citizens (and prosecutors) to a fair trial.

—

Joel Cohen, a former state and federal prosecutor, practices white collar criminal defense law as Senior Counsel at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan. He is the author of “Broken Scales: Reflections On Injustice” (ABA Publishing, 2017) and an adjunct professor at both Fordham and Cardozo Law Schools.

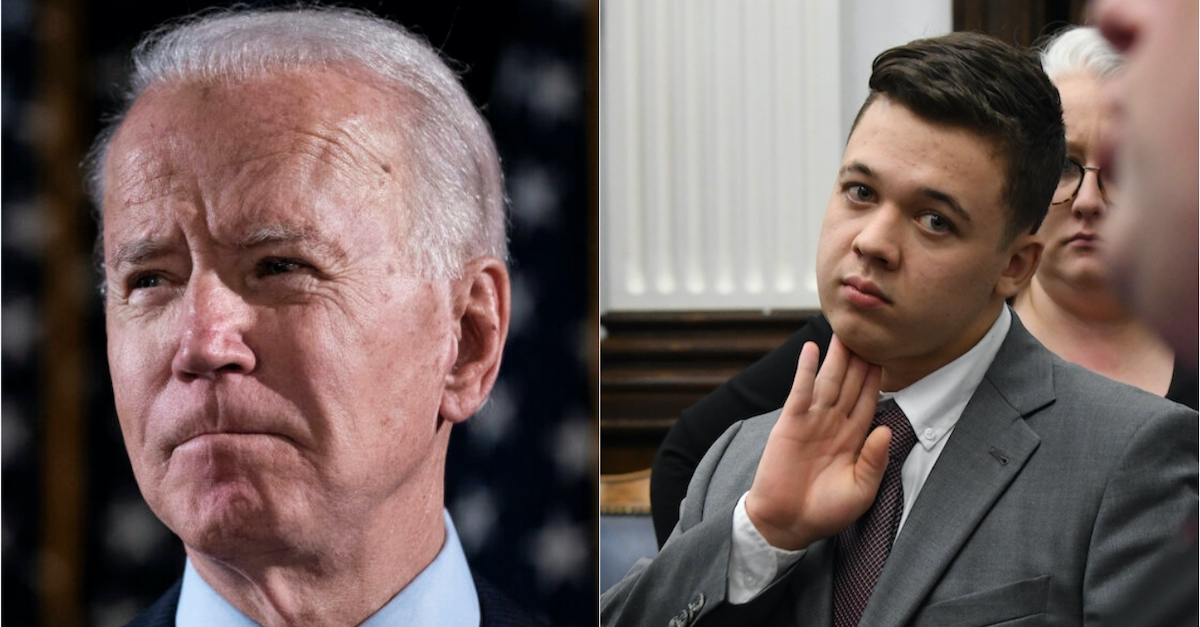

[Photo of Biden via Drew Angerer/Getty Images; Photo of Rittenhouse © Mark Hertzberg/ZUMA Press Wire/Pool]

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.