It’s easy to think that every SCOTUS decision breaks along left/right lines, but in truth, there are lots of legal decisions that just don’t work that way. Monday saw seemingly unlikely allies Neil Gorsuch and Sonia Sotomayor team up in a dissent on a cert denial that proved both justices to be rather criminally-defense minded.

The majority of the Court denied certiorari, declining to hear the case of Stuart v. Alabama, a drunk-driving matter in which Vanessa Stuart argued that her Constitutional rights were violated when she was prevented from cross-examining the state’s scientist about her blood-alcohol test results. The State of Alabama chose to put a different analyst on the stand who estimated Stuart’s blood-alcohol level; as a result, Stuart could not cross-examine regarding the specifics of the blood testing.

According to Gorsuch, whose dissent was joined by Sotomayor, Alabama’s conduct amounted to violation of Stuart’s rights under the confrontations clause. He wrote that not only should SCOTUS have taken up the case, but also that Stuart should win it: “The engine of cross-examination was left unengaged, and the Sixth Amendment was violated.”

If you’re thinking that Gorsuch seems a little too bleeding-heart to be filling Antonin Scalia’s seat, you’d be wrong. Scalia himself would almost certainly have ruled the exact same way. According to the late justice, the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee that an accused “shall enjoy the right … to be confronted with the witnesses against him,” has two aspects: a defendant’s right to challenge actual witnesses, and the right to bar any testimony from witnesses who did not or cannot testify in court.

In fact, Scalia ruled that way even in cases that threaten to push the limits of the most left-leaning jurists. Scalia reversed the conviction of a man who murdered his girlfriend, because evidence was introduced at trial that the victim had reported the defendant’s threats. Since the woman’s death (obviously) prevented her from being cross-examined at trial, second-hand testimony about her threats constituted reversible error. Scalia was no stranger to the multiple-lab-analysts problem either. He joined 5-4 majorities, reversing both a drug conviction when Massachusetts failed to bring in the actual lab analyst who confirmed that bags of white powder were cocaine, and a drunk driving conviction when New Mexico failed to bring in the analyst who worked on the defendant’s blood sample. In Scalia’s mind, a criminal defendant must get a crack at all of the evidence introduced against him; anything less is a major no-go.

In Gorsuch’s dissent on the denial of cert in the drunk-driving case, he bluntly blamed SCOTUS itself for the underlying dilemma. Gorsuch wrote, “the problem appears to be largely of our creation,” and lamented the confusion stemming from what he called “fractured” precedents.

Gorsuch specifically called out the reality that Law & Crime’s trial-watchers will know well – that forensic evidence increasingly plays a decisive role in many criminal trials. With forensic evidence, there is always a danger of manipulation, contamination, and simple error, and Gorsuch would have a hand in ensuring that criminal defendants are not thereby prejudiced: “To guard against such mischief and mistake and the risk of false convictions they invite, our criminal justice system depends on adversarial testing and cross-examination.”

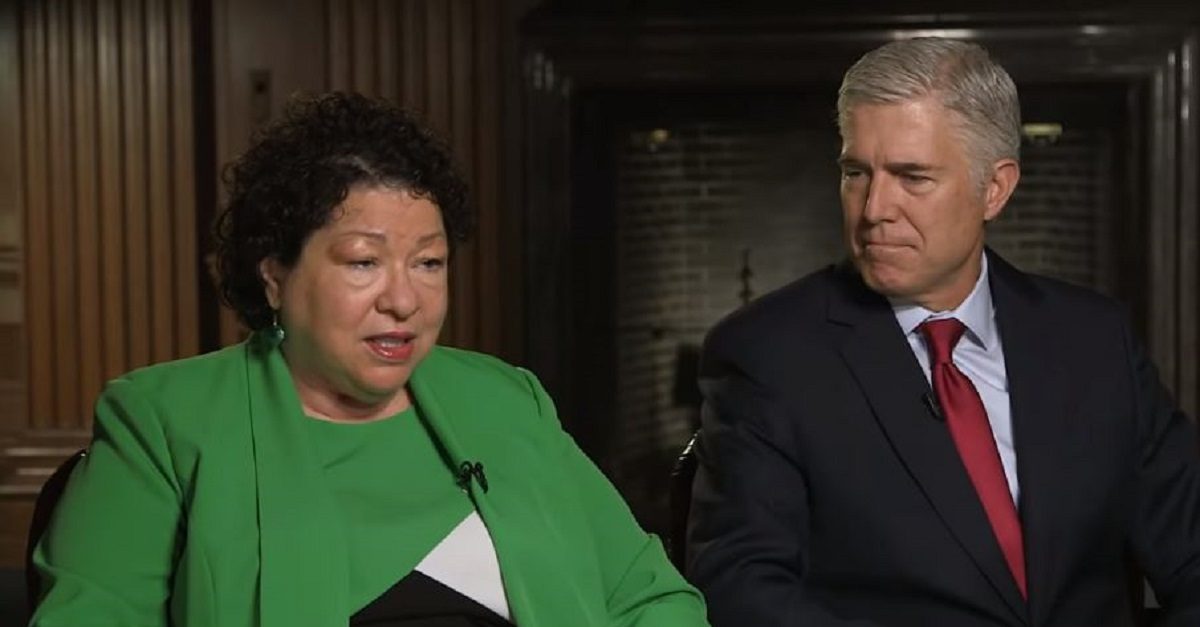

[Image via CBS screengrab]

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.