The U.S. Supreme Court court didn’t do much on Monday, but Justice Clarence Thomas still managed to put in his two pence—twice—when appealing to the way things were done at both the English Court of Chancery and British Parliament centuries ago.

The high court denied certiorari in Kansas v. Boettger, a case in which the Kansas Supreme Court overturned separate criminal convictions for the making of threats. Timothy Boettger had been convicted for telling the son of a police detective that he “‘was going to end up finding [his] dad in a ditch”; Ryan Johnson was convicted for telling his mother that he “‘wish[ed] [she] would die.’”

On appeal, the state court overturned both men’s convictions on the basis that the threats had been merely “reckless” (as opposed to threats made with intent to intimidate) and were therefore protected by the First Amendment. That decision, however, conflicts with decisions on the same issue rendered the Supreme Courts of Connecticut and Georgia.

If Justice Clarence Thomas had his way, SCOTUS would have the chance speak up on this particular First Amendment issue, settling the rule about reckless threats once and for all. Thomas’s reasoning on the subject was something of a head-scratcher, though. His primary argument was that the folks in jolly olde England would have criminalilzed reckless threats, and so too should we.

Thomas embarked on a bizarre postmortem, wrestling over the Founding Fathers’ opinions on reckless threats in light of English history. He regaled the tale of how British Parliament passed a statute in 1754 “making it a crime to ‘knowingly send any Letter without any Name subscribed thereto, or signed with a fictitious Name . . . threatening to kill or murder any of his Majesty’s Subject or Subjects, or to burn their [property], though no Money or Venison, or other valuable Thing shall be demanded.’” The conservative justice went on to describe how English courts had interpreted that statute, and how that interpretation formed the underpinnings of the modern-day concept of general intent. Thomas even quoted British jury instructions in a 1776 case.

I like history as much as the next guy. And in many contexts, knowledge of a historical concept is critical to accurate legal analysis. But this nonsense bypasses “oblique and irrelevant” and lands squarely on “willfuly obtuse.” The Founding Fathers created the United States because they were unhappy with how things were going in England. The Constitution was drafted nearly half a century after the statute Thomas cited. And when that Constitution was adopted, the very first freedom it enumerated was Freedom of Speech. If we’re deciding what American “freedom of speech” means in 2020, asking colonial Britain doesn’t seem likely to provide an accurate answer.

Thomas’s conclusion about whether the First Amendment protects reckless threats may be correct—but if it is, it’s not because of what men an ocean away did with their country. If there is anyone who should be sticking to the values and ideals of our country, it’s the Supreme Court.

The Court also issued an 8-1 opinion Monday in Liu v. Securities and Exchange Commission. In that case, which dealt with what remedies are proper for securities violations, Justice Anglophile was again the lone dissenter. And Thomas went off again on how things should be based on how they once were in England.

The case involved individuals who solicited foreign nationals to invest in the construction of a cancer-treatment center, and then misappropriated the investment funds. The SEC brought a civil action against the wrongdoers and won. At issue was what that win actually means. The District Court held that the individuals were liable for the full amount of their ill-gotten gains. The petitioners, however, argued that they shouldn’t have to give back all the money – because some of the investment funds went to legitimate business expenses.

In legalese, the issue was whether “disgorgement” (the action of stripping wrongdoers of all ill-gotten gains) is allowed in this particular securities case. While the other eight justices ruled to allow disgorgement, Justice Thomas wasn’t having it. His reasoning? Disgorgement isn’t a “traditional equitable remedy.” And by “traditional,” Thomas is looking at the legal standards of Merry Olde England. “Because disgorgement is a creation of the 20th century,” Thomas wrote, “it is not properly characterized as ‘equitable relief,’ and, hence, the District Court was not authorized to award it under §78u(d)(5).”

Time for a little history break. Before, America existed, the English court system was divided into two kinds of courts: courts of equity and courts of law. Courts of law (which handle cases in tort or criminal law) were required to interpret statutes and case law down to the letter in every case; by contrast, equity courts (which handled contracts or family law cases) were expected to create outcomes of general fairness in the cases before them. Equity courts had much wider latitude in fashioning outcomes – but were not permitted to impose penalties on litigants. Okay, back to present-day America.

Justice Thomas’s beef with the majority is that the Securities Exchange Act authorizes the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to seek only, “equitable relief that may be appropriate or necessary for the benefit of investors.” According to Thomas, “the history is clear: Disgorgement is not a form of relief that was available in the English Court of Chancery at the time of the founding.”

Thomas accused the majority of applying the remedy of disgorgement in a way that “threatens great mischief.” Why? Because “the term disgorgement itself invites abuse because it is a word with no fixed meaning.” Yes, yes. I, too, am deeply concerned that there will be “great mischief” if the Ninth Circuit doesn’t conduct itself the way the English Court of Chancery would have. At a minimum, I might misplace my barrister’s wig while I am en route to the Old Bailey.

Justice Thomas’s near-obsession with deciding cases just as they’d have been decided in Georgian England is beginning to sound less like a gathering of historical context and more like “long live the Queen!”

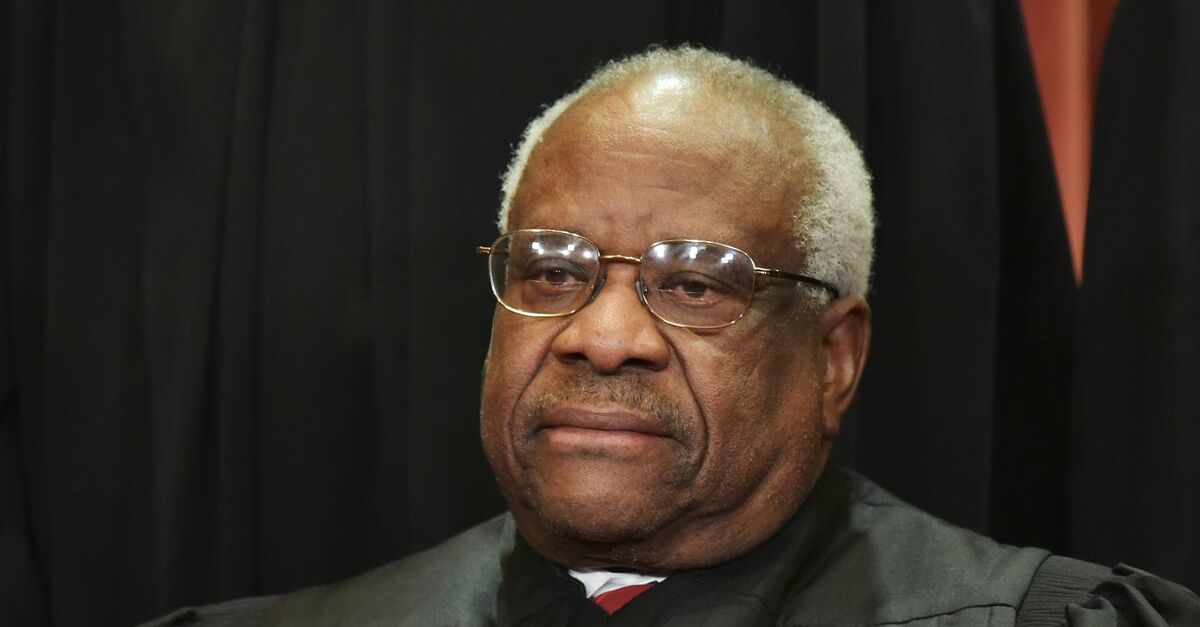

[image via Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images]

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.