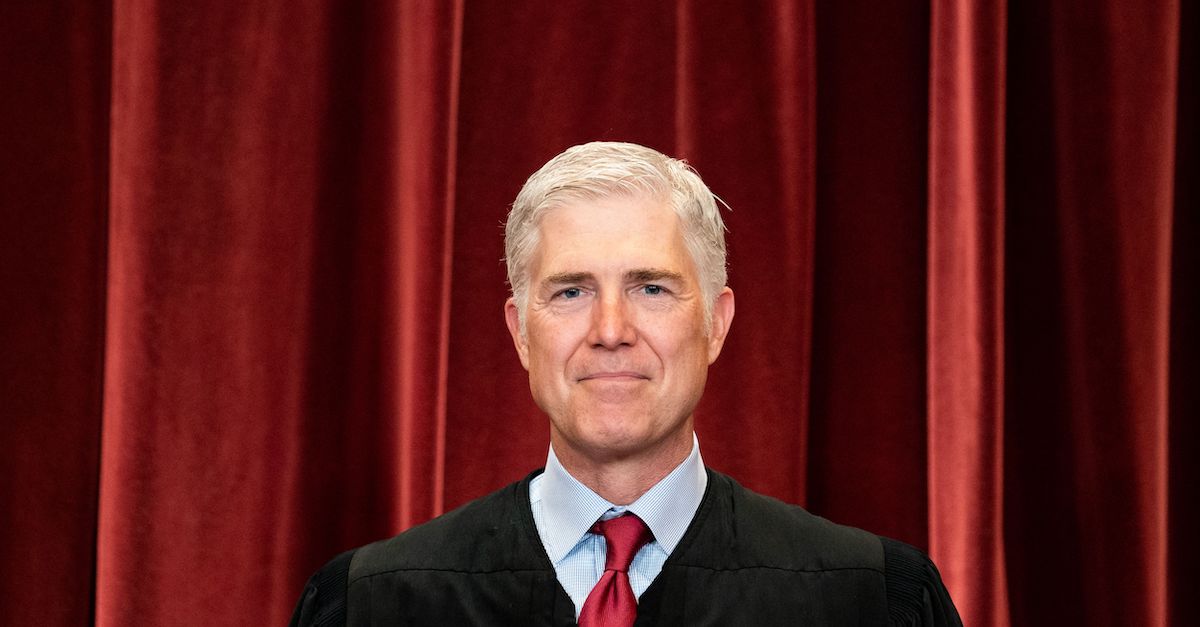

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch stands during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021.

Justice Neil Gorsuch sharply decried “judicial abdication” in the face of a longstanding precedent that empowers administrative agencies in a case about veterans’ disability benefits that was rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court in orders published Monday morning.

Dissenting from the denial to grant the petition for writ of certiorari in the case stylized as Buffington v. McDonough, the justice took up one of his oft-lit candles — veterans being forced through the administrative wringer — while railing against one of his least-favorite high court mandates, Chevron deference. As is often the case in opinions written by the first Donald Trump nominee appointed to the Supreme Court, the treatment of veterans and the so-called “administrative state” are inseparably linked.

Notably, the textually-inclined conservative justice’s broadside against Chevron includes a reference to the notion of regulatory capture — a concept that was pioneered by socialist American historian Gabriel Kolko.

Gorsuch recapped the facts of the case. After eight years in the Air Force, Thomas Buffington “suffered a facial scar, a back injury, and tinnitus,” the dissent explains. Then, he joined the Air National Guard but was out of service for three years. During that three-year hiatus, he was found to be partially disabled and entitled to benefits – which were paid out. In 2003, his unit was called up and he served, on and off, until leaving active duty in 2005. During his time back in service, the benefits were paused.

But the Department of Veterans Affairs did not start paying the veteran’s benefits again when he left active duty status. Buffington later realized what was going on and asked about the discrepancy in 2009, requesting backpay. The VA said the payment issue was his fault because he did not ask for his entitled benefits to restart sooner and denied his request based on internal agency rules.

Buffington appealed to the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit – with no luck.

“I very much doubt that the courts below did right by Mr. Buffington,” Gorsuch said in his dissent on Monday, relying solely on the underlying statute mandating payment. “Congress has instructed the VA to make disability payments to injured veterans like Mr. Buffington. In §5304(c), Congress suspended that obligation only for periods when a veteran ‘receives active service pay.’ Nothing in the statute requires a veteran to ask the agency to resume benefits it is already legally obligated to pay.”

Both lower courts denied Buffington relief and upheld the VA’s rules – which purport to interpret the relevant federal statute establishing veterans’ benefits – by relying on the framework from the landmark case of Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. That 1984 case created a multiple-step inquiry that determines whether an administrative agency is entitled to judicial deference to its own interpretation of a statute written by Congress.

Considered the bedrock of the fourth branch of government — the administrative state — Chevron‘s first step is to ask whether or not “Congress has directly spoken to the precise question at issue,” which is another way of asking whether the statute is ambiguous. Typically, a lower court will only consider the additional steps if the statute is found to be ambiguous. The number of steps any given court allows itself to take in any given case is often dispositive in how the court rules.

Gorsuch has long worn his distaste for Chevron on his sleeve and has occasionally implored other judges to reconsider its application.

His dissent rebuffs the lower courts in Buffington in harsh terms:

Even more troubling than the answer the lower courts reached in this case, however, is how they got there. Neither the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims nor the Federal Circuit offered a definitive and independent interpretation of the law Congress wrote. Instead, both courts simply deferred to the agency’s (current) regulations as “reasonable” ones and said this Court’s decision in Chevron required them to do so. That kind of judicial abdication disserves both our veterans and the law.

Gorsuch goes on to feint at an almost-attempt to salvage the opinion by offering a more nuanced reading that cites parts of the landmark case almost never used by reviewing courts, writing that “Chevron did not express disagreement with (let alone purport to overrule) precedents reciting the traditional rule that judges must exercise independent judgment about the law’s meaning” and that the original opinion cited cases supporting the idea that “courts afford respectful consideration, not deference, to executive interpretations of the law.”

As the dissent goes on, the justice uses this atypically nuanced take on Chevron to catalog that the “broad” reading and reconstruction of Chevron deference is largely a “disavowed” and defunct and “project” that lower courts have largely abandoned. The case is increasingly used sparingly, the dissent notes, as judges often invoke other principles of statutory interpretation “when they can.”

Still, the dissent says, broad Chevron readings loom:

Overreading Chevron holds still other consequences for the rule of law. When the law’s meaning is never liquidated by a final independent judicial decision, when executive agents can at any time replace one reasonable interpretation with another, individuals can never be sure of their legal rights and duties. Instead, they are left to guess what some executive official might “reasonably” decree the law to be today, tomorrow, next year, or after the next election.

…

Nor does everyone suffer equally. Sophisticated entities may be able to find their way. They or their lawyers can follow the latest editions of the Code of Federal Regulations—the compilation of Executive Branch rules that now clocks in at over 180,000 pages and sees thousands of further pages added each year. The powerful and wealthy can plan for and predict future regulatory changes. More than that, they can lobby agencies for new rules that match their preferences. Sometimes they can even capture the very agencies charged with regulating them. But what about ordinary Americans?

“No measure of silence (on this Court’s part) and no number of separate writings (on my part and so many others) will protect them,” Gorsuch writes, castigating his colleagues for denying the veteran’s petition. “At this late hour, the whole project deserves a tombstone no one can miss. We should acknowledge forthrightly that Chevron did not undo, and could not have undone, the judicial duty to provide an independent judgment of the law’s meaning in the cases that come before the Nation’s courts. Someday soon I hope we might.”

[image via ERIN SCHAFF/POOL/AFP via Getty Images]

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]