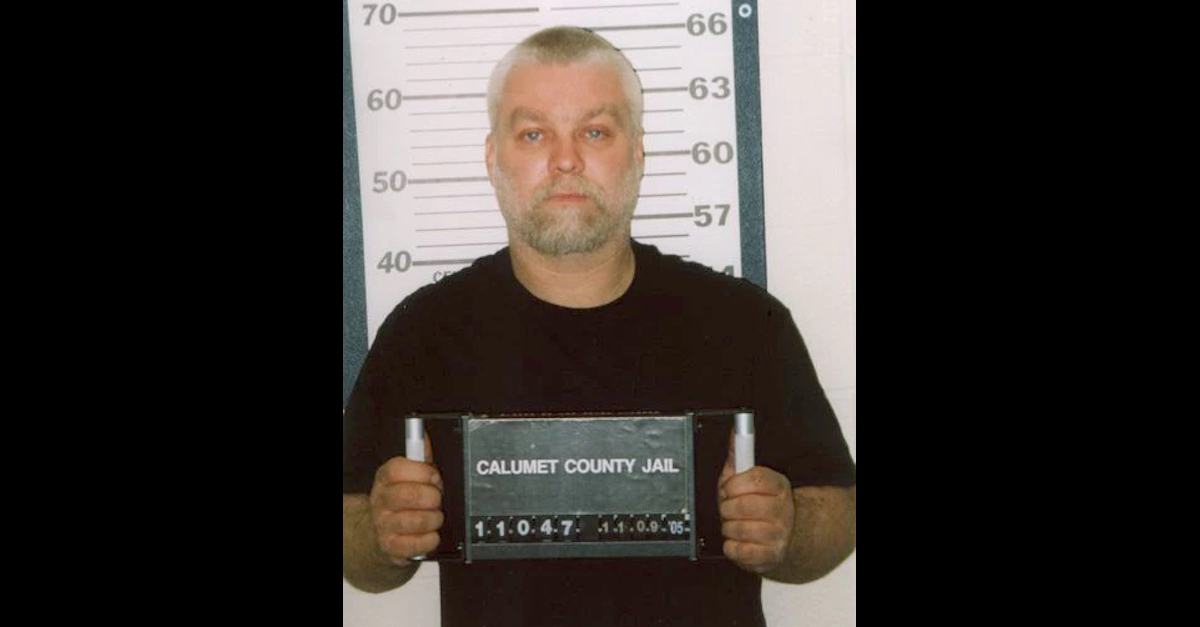

Steven Avery is seen in a 2005 mugshot taken by the Calumet County, Wisconsin jail.

The Wisconsin Court of Appeals on Wednesday morning denied a deluge of motions for post-conviction relief by Steven Avery, the central figure in the Netflix docuseries Making a Murderer. The unsigned per curiam opinion contains no concurrences and no dissents — indicating that the panel was unanimous.

Sixteen judges hear cases on the state court of appeals; each case is generally heard by three judges. In Avery’s case, Chief Judge Lisa S. Neubauer, Presiding Judge Paul F. Reilly, and Judge Jeffrey O. Davis made up the panel, and all three judges spoke for the court. Their opinion legally foreclosed many of Avery’s attacks on his 2007 conviction in the murder of freelance photographer Teresa Halbach and served as a de facto rebuttal to many of the theories explored in Making a Murderer Part 2 — even though the multi-season, multi-episode production was named in the opinion only once.

Avery defense attorney Kathleen Zellner said it provided a narrow window for future attacks on Avery’s long-debated conviction.

“Not deterred by the appellate court decision,” Zellner said in a Wednesday morning tweet. “[I]t pointed out the specific doors that are still open for Mr. Avery’s quest for freedom. We appreciate the careful review.”

On Tuesday, before the Court of Appeals largely rubbished her case on both the facts and the legal tactics she employed , Zellner said she was “hoping justice prevails” but that her “quest never ends until Steven is free.”

Teresa Halbach is seen in front of her Toyota RAV 4. key(Image via Calumet County, Wis. court files.)

The Court of Appeals opinion examined a sum total of six defense motions which have been moving through Wisconsin state courts since 2016. That smattering of arguments were the subject of voluminous briefs, motions, affidavits, and exhibits in an attempt to flip Avery’s storied and convoluted conviction, and the Court of Appeals examined each in turn. The court recapped the legal moves in brief while ultimately deciding that Avery was not entitled to the relief he sought — at least not right now:

The issues in this new case concern collateral proceedings: whether the circuit court erred in denying Avery’s WIS. STAT. § 974.06 (2019-20) motion and two supplemental motions without a hearing, as well as his motions to vacate and for reconsideration of the first of these motions. We hold that Avery’s § 974.06 motions are insufficient on their face to entitle him to a hearing and that the circuit court did not erroneously exercise its discretion in denying the motions to vacate and for reconsideration. Accordingly, we affirm.

The 49-page opinion leans heavily on state procedural statutes. As the opinion notes, Wisconsin law — generally speaking — “promotes finality once the defendant has been convicted and sentenced.”

Here is a summary of the Court of Appeals holdings on each of Zellner’s six motions.

Motion 1 — June 2017

This appellate motion arose from a 2016 motion before Avery’s trial court to secure independent testing on nine separate trial exhibits: “seven samples of bloodstain cuttings, swabs, or blood flakes taken from Halbach’s RAV4; Halbach’s RAV4 key; and a 1996 sample of Avery’s blood.” Avery eventually asked for a new trial “on the results of this testing and other investigations,” the Court of Appeals noted.

A smear of Steven Avery’s blood was discovered near the ignition switch in Teresa Halbach’s SUV. Prosecutors have long argued it is proof Avery is the killer; Avery has long argued the blood was planted. (Image via Calumet County, Wis. court files.)

Among Avery’s claims were that his trial attorneys — Jerry Buting and Dean Strang — provided ineffective assistance of counsel. Avery also claimed (through his new attorney) that his prior pro se attempt to litigate his own appeal was also ineffective.

The Court of Appeals rubbished many of the ineffective assistance of counsel claims as to Buting, Strang, and Avery himself by noting that successive motions on appeal cannot “turn[] into something akin to Russian nesting dolls, wherein a litigant can simply allege a continuous series of ineffective assistance of counsel claims to justify previous failures to raise an issue.” Avery’s learning disabilities, his status as a prisoner of modest monetary means, and his lack of knowledge of the law and the facts — all issues Zellner has long argued should allow the court to override Avery’s earlier claims — were legally pointless, the Court said, given that Wisconsin law provides defendants with one chance to raise an appeal under Wisconsin Statute § 974.06, the unsympathetic court explained a length:

Avery gives us bare-bones factual conclusions but does not meaningfully explain why the circumstances he describes precluded him from raising most of these issues earlier.

[ . . . ]

Avery does not explain, and we cannot envision, why he did not have all the facts necessary in 2013 to raise these claims (which, after all, are premised on the further investigation of evidence and witnesses known to Avery at the time of trial).

[ . . . ]

A defendant’s pro se status, standing alone, cannot excuse his or her failure to raise claims in a WIS. STAT. § 974.06 motion.

With one exception — discussed below — Avery’s remaining reasons are similarly deficient. Avery simply claims that he has a learning disability and was indigent in 2013, and that his case is complex. He does not cite any law, or develop any detailed argument, as to why these facts, alone or taken together, explain his failure to raise these claims. It appears well established from federal habeas law, from which we can borrow, that reasons such as these are not the sort of grounds on which a procedural bar can be avoided.

The “exception,” the Court of Appeals said, allowed further inquiry into some, but not all, of Zellner’s theories of the case. The court explained in a footnote that some of the evidence Avery has purported to be new or novel is really just a different look at old evidence that’s long since been debated, such as whether or not the key to Halbach’s vehicle fell out of his nightstand the way a law enforcement officer claimed it did at trial.

Manitowoc County deputies said they found the key to Teresa Halbach’s SUV when they jostled a nightstand in Steven Avery’s trailer. Avery said the key was planted. (Image via Calumet County, Wis. court files.)

Through a complicated series of multi-paragraph footnotes and concomitant full-page arguments, the Court of Appeals, in essence, said the “result of the proceeding” — that is, Avery’s jury trial — would probably not have been different even if Avery’s trial counsel retained a blood spatter expert, a trace materials expert, a DNA expert, and a forensic fire expert to help argue his case. The Court of Appeals said Zellner’s lawyering was unpersuasive on the law in one lengthy footnote:

Avery fails to demonstrate how the defense strategies that trial counsel did pursue rendered counsel’s performance constitutionally deficient. As an example, he points to trial counsel’s failure to obtain a blood spatter expert but does not address why counsel’s chosen strategy for explaining the presence of his blood in the RAV4 represented deficient performance at the time of trial, without the benefit of hindsight. This is a repeated shortcoming in Avery’s briefing, both to the circuit court and on appeal, and represents exactly the type of “Monday- morning quarterbacking” that we strive to avoid in evaluating a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel.

Nor was Zellner’s evidence persuasive, the court rationed in a series of slams aimed at Zellner’s characterization of her own experts’ conclusions. For instance, Zellner claimed that the sheer volume of Avery’s DNA found on Halbach’s car key suggested that the DNA on the key was planted or doctored by the government. Zellner said that a test whereby Avery held a sample key in recent years didn’t yield anywhere near the amount of DNA the government found on Halbach’s key in the mid-2000s. The Court of Appeals said Zellner’s claim stretched even her own experts’ findings too far:

[T]he findings of Avery’s expert are significantly more ambiguous than what is presented in his motion. We have no reason to doubt the truth of these findings (although we note that the expert did not observe Avery holding the key), but simply determining that Avery deposited significantly less DNA in a controlled experiment does not indicate that Avery could not or did not deposit more DNA under other conditions, and it certainly does not demonstrate that law enforcement planted DNA on the key. Thus, even accepting the truth of these new findings, we cannot conclude that there is a reasonable probability that their introduction at trial would have led to a different result.

Volunteer searchers say they found Teresa Halbach’s Toyota RAV 4 partially hidden on the Avery family salvage yard. (Image via Calumet County, Wis. court files.)

Later, the Court of Appeals accused Zellner of “misrepresent[ing] the facts” as to another hotly debated issue: Avery’s DNA on the hood latch of Halbach’s vehicle:

Avery’s sixth claim is that counsel was ineffective for not retaining a DNA expert, who would have determined that DNA from Avery’s sweaty hands “was never deposited [by Avery] on the RAV4 hood latch,” demonstrating that “Mr. Avery was being framed.” In what is becoming a pattern, Avery has misrepresented the facts. The DNA expert Avery has now hired did not determine that Avery “never deposited” the DNA and did not state that Avery was framed. Instead, the expert performed a series of experiments on an identical vehicle, wherein volunteers opened the car hood using the hood latch. Only four of the fifteen volunteers deposited DNA, and those four deposited significantly less DNA than present in the swab from Halbach’s RAV4 hood latch. From this experiment, the expert extrapolated the possibility that law enforcement could have retrieved and relabeled a swab of Avery’s groin (which was collected and discarded for exceeding the scope of a search warrant) as coming from the hood latch. The expert admitted, however, that “the convenience of this explanation … and the fact that it accounts for the physical findings observed from the analysis … does not prove evidence tampering, or more precisely, evidence reassignment.” Thus, again, we are left with facts that, even if true, would not entitle Avery to relief: in a controlled experiment, the minority of volunteers who deposited sweat on the RAV4 deposited significantly less sweat than on the swab recovered by law enforcement. There is no context to these findings—no showing of why Avery, under noncontrolled conditions, could not have deposited more sweat than the volunteers, much less any showing that the DNA was therefore planted. Without such context, this evidence is not exculpatory or even particularly relevant, and Avery’s attempt to link it to the alleged reassignment of his groin swab is wholly unsupported by any facts of record.

The page-by-page dismissal of Zellner’s articulated theory of the case continued.

“Avery’s cited factual support once again does not live up to the advance billing,” the Court of Appeals said with reference to arguments that Halbach’s bones were planted in Avery’s burn pit. “Avery does not explain why, from this conclusion, it follows that Halbach’s remains were planted, because he does not explain why he himself would have been unable to cremate some portion of Halbach’s body in another location—including in his burn barrel, where additional bone fragments were found,” the Court rationed; “[m]ore important, Avery does not explain where or how prejudice arises, given that his own forensic anthropologist testified to this same conclusion at trial.”

To further make the point:

In sum, the seven ineffectiveness claims in Avery’s June 2017 motion that are based on new investigations fail on the merits. Avery has not shown that trial counsel provided objectively deficient representation by not hiring experts similar to those he later hired. Instead, Avery merely assumes that the need for such experts should have been obvious at the time, based on the later findings of his own experts. These later findings, however, are either equivocal, irrelevant, or both. In addition, Avery has not explained how these findings would have negated or undermined the cumulative effect of the other trial evidence. Thus, Avery has failed to show that, even if all these findings were admitted at trial, the result would have been different. Consequently, Avery has not alleged sufficient material facts entitling him to a hearing on his claims of ineffective assistance of counsel.

As to alleged violations of Brady v. Maryland, the 1963 U.S. Supreme Court case which generally requires the police to give favorable evidence to the defense, the Court of Appeals concluded that “Avery’s June 2017 motion does not sufficiently allege any Brady violations.”

A still frame from flyover video shows a grainy, 2005-era standard definition image of the Avery salvage yard, where prosecutors have long argued Teresa Halbach was murdered.

One such item which the defense claims the prosecution failed to hand over is an allegedly unedited version of a video of the Avery family property and salvage yard where Halbach’s vehicle was retrieved. Footage presented to the defense from an airplane flyover did not show the area where Halbach’s car was retrieved days later. Again, the Court of Appeals:

As far as we can tell, this claim is based only on Avery’s unsubstantiated belief that a second video must exist because the airplane was in the air for four hours but the video he received was only three minutes long. There is no evidence of a Brady violation here because Avery merely speculates that evidence not even known to exist was suppressed.

Close observers of the case immediately trounced the Court of Appeals for not fully analyzing a chain of emails which suggested raw video does exist in some fashion or another — though the emails don’t directly state that the footage provided to the defense at trial was edited as Zellner claims.

The Court of Appeals then rubbished Zellner’s attempt to make a Brady violation out of claims that Halbach’s car was driven onto property owned by an Avery neighbor. Calling Zellner’s argument “unintelligible” in general, the Court of Appeals said that “there was no evidence here to suppress” at the time of trial because the neighbor’s claims were new; even then, “the facts in the affidavit are inconsequential” for the purposes of a new trial, the Court held.

Further claims by Avery that new technology invented nearly 10 years after his trial could have tilted his conviction the other way were also unpersuasive because he did “not address whether technology available at the time of trial could have yielded the same results,” the Court of Appeals said. And, even then, the “evidence is largely irrelevant,” the Court found.

As to whether a bullet in Avery’s garage somehow helped prove his innocence, the Court of Appeals again jettisoned Avery’s claims as a stretch of the truth:

The premise of his first claim is that, if the damaged bullet found in his garage did not deliver Halbach’s fatal shot to the head, then he could not be the perpetrator. But the State never argued that either of the bullets recovered from Avery’s garage killed Halbach. At trial, the State showed that Avery’s gun fired the bullet and that the bullet had Halbach’s DNA on it. But the State did not argue that this specific bullet entered Halbach’s skull or killed her (nor was it necessary that it do so in order to implicate Avery in her murder). There is nothing to suggest that shots fired into Halbach’s skull were the only shots fired at her or that every bullet fired at her contained skull fragments—there were, after all, eleven casings and only two bullets found in the garage. The presence of Halbach’s DNA on a bullet found in Avery’s garage is particularly damning evidence—regardless of whether it was the bullet that entered her skull—and strongly implicates Avery absent evidence that Halbach’s DNA was planted (a supposition that, even now, Avery has done little to develop). At the very least, Avery’s new evidence — if it in fact is new — is consistent with the State’s theory of the crime.

“We have given Avery the benefit of several doubts as to why he did not raise these claims earlier,” the court said while rubbishing the June 2017 motion. “Even considered on the merits, the claims asserted in his June 2017 motion are speculative, conclusory, and in some cases misleading. The circuit court did not err in denying these claims without a hearing.”

Attorney Kathleen Zellner is seen in a screengrab from a Netflix trailer.

Motion 2 – October 2017

The Court of Appeals said this motion “misses the mark entirely.” Though the Court noted that “Avery appears to acknowledge these basic principles of postconviction procedure,” he “[n]onetheless . . . argue[d] that the circuit court erroneously exercised its discretion.” The Court of Appeals said the circuit court was well within its discretion to refuse “to revisit its decision on the June 2017 motion upon being belatedly informed that Avery wished to amend that motion.”

Motion 3 – October 2017

The Court of Appeals seemed irritated that a so-called Avery “motion to reconsider” actually delved into some topics which were new — and did so “without applying” the correct “legal standard.”

The Court of Appeals said that the lower circuit court was within its discretion to toss the motion as to claims that could have been raised earlier, but the appellate judges said that some of the new claims could, in theory, be the subject of a future motion on their own. Those claims included questions about who had possession of Halbach’s day planner after her death and whether law enforcement ignored reports that Halbach’s SUV was spotted off the Avery property after Halbach’s death but before it was formally found by volunteer searchers. Those questions were not the subject of lower court rulings, and the Court of Appeals was not willing to touch them without a lower judge issuing a decision. But the Court of Appeals still rubbished them in a footnote: “[t]he evidence Avery submits, however, does not and cannot reasonably be construed to support this conclusion.”

Also “buried in the motion” — according to the Court of Appeals’ telling — were claims that Barb Tadych, Avery’s sister, was willing to impeach her son Bobby Dassey’s testimony at trial. (Dassey is the brother of Avery’s co-defendant Brendan Dassey, who was tried and convicted separately.) The Court of Appeals rubbished the importance of that information (some citations omitted here):

In Avery’s view, his sister “admitted that she knew that [Halbach] had left the property” on the day in question. This evidence, however, is equivocal and does not clearly establish that Halbach in fact left the property on the day of her death or that any witness was aware of or lied about this fact at trial. Moreover, the evidence does not bolster any claim in the June 2017 motion so as to warrant reconsideration of that motion. Even viewed on its own merits, the evidence does not entitle Avery to a WIS. STAT. § 974.06 hearing because he has not shown that it is material. At best, we have two unsworn statements by Barb Tadych that Dassey told her something that is potentially inconsistent with his trial testimony. This is hearsay that would be inadmissible at a new trial, meaning that it cannot constitute newly discovered evidence as a matter of law.

“[W]e are willing to give Avery the benefit of the doubt, where possible, as to why he did not raise certain claims in 2013 or on direct appeal,” the Court of Appeals noted while dismissing many of Avery’s claims on procedural grounds. “But we cannot ignore the law” that gives rise those procedures, the court said.

The Court of Appeals agreed that the circuit court was correct by chiding Zellner for “prematurely” filing many of her arguments while “considerable investigation was still being conducted by the defense.”

The Court of Appeals noted that the lower circuit court judge who examined this original motion misconstrued it as a complaint about appellate counsel; still, the Court of Appeals indicated that the circuit court judge was correct to toss the arguments as they were framed by Zellner.

Motion 4 – July 2018 Supplemental Motion

The Court of Appeals agreed with the lower circuit court that the authorities committed no Brady violation when they failed to hand a summary CD of material from the Dassey family computer over to Avery’s trial lawyers. The CD only contained a summary of material that was already handed to the defense in full on series of seven DVDs, the Court of Appeals said. And again, the judges accused Zellner of bungling the law: “Brady on its terms applies to favorable and material suppressed evidence, and Avery has presented no authority extending this principle to the prosecution’s withholding of secondary compilations or analyses of such.” And though Zellner claimed that the prosecution tried to mislead Avery’s trial team by characterizing the DVDs as having “not include[d] much of evidentiary value,” the Court of Appeals said that such “an off-the-cuff description of disclosed evidence cannot form the basis for a Brady violation.”

Here, the Court of Appeals dismissed suggestions that the Dassey computer — which was full of violent pornography — could have tied Bobby Dassey to the Halbach killing.

“To admit evidence at trial that Dassey could have killed Halbach, Avery would have had to provide some evidence . . . directly connecting Dassey to the crime,” the Court of Appeals said. “That Dassey possibly possessed violent pornographic images might have conceivably satisfied a separate requirement, motive, but is insufficient in and of itself to allow admission of third-party liability evidence” under Wisconsin law. Moreover, the Court of Appeals said that using the Dassey computer to impeach Bobby Dassey would likely have gone nowhere:

Avery does not explain how impeaching Dassey about his use of the computer would have changed the outcome of the trial. At most, the jury would have disbelieved Dassey’s testimony that, on the day Halbach last visited the Avery property: he saw Halbach walk towards Avery’s trailer, he did not see her leave the property, Halbach’s RAV4 was in the driveway when he left to go hunting, and the RAV4 was gone when he returned several hours later (Avery identifies these as the key pieces of testimony). Certainly, this testimony bolstered the State’s theory that Halbach visited Avery on that day and did not leave the Avery property thereafter, but absent this testimony, the State still possessed significant forensic (and other) evidence implicating Avery in a crime committed on his property. Without any showing or argument as to why the impeachment of Dassey would have undermined the cumulative effect of the other evidence, we cannot conclude that the trial’s outcome would have been different. We conclude that the circuit court did not err in denying the July 2018 motion without a hearing.

The Court of Appeals said Zellner “misrepresented some key facts underlying” the claim that the computer was relevant to the case. But it did again invite Zellner to file some of her claims for first impression upon the lower circuit court for a judge there “to decide in the first instance” whether the claims had merit. If Zellner takes that route, the Court of Appeals warned that the claims would have to survive a considerable degree of scrutiny.

Motion 5 – March 2019 Supplemental Motion

This motion argued that bones found in a gravel pit adjacent to the Avery family property were returned to the Halbach family in violation of a court order and of a state law. Avery sought to have the remains tested for DNA to see if they were Halbach’s. He argued that the state’s decision to hand the bones over to the Halbach family was an admission that the bones were, indeed, Halbach’s. Avery suggested that the bones were put there by someone else, but the Court of Appeals said they do not “indicate that another person killed Halbach.” Rather, “Avery never explains why he himself would have been unable to dispose of Halbach’s remains in the gravel pit,” the Court of Appeals said. Because Avery’s “reasoning is wholly speculative” as to the meaning of the bones, and because the evidence was not “apparently exculpatory,” Avery’s argument was unconvincing.

An evidence photo shows a box of bones submitted to a forensic anthropologist for examination. (Image via Calumet County, Wis. court files.)

Motion 6 – April 2021 Motion to Stay and Remand

This motion sought to argue that a newspaper delivery man saw “[Bobby] Dassey and an unidentified older man pushing Halbach’s vehicle down Avery Road towards the junkyard” days after Halbach’s death. The Court of Appeals said the lower circuit court needed to rule on the issues presented by the evidence before it could examine the matter.

Again, the Court of Appeals criticized Zellner for asking it to examine something the lower court had not fully considered.

“Avery’s latest motion arrived while our decision on his appeal was forthcoming. It would be an inefficient use of court resources to now, and once again, delay this appeal’s resolution,” the appellate judges said.

Avery must raise this and other outstanding claims before the circuit court — all while proving “why he could not have previously raised th[e] claim[s]” in his earlier motions.

“Simply put, Avery’s appeal cannot continue indefinitely,” the court said.

It concluded:

Avery raises a variety of alternative theories about who killed Halbach and how, but as the State correctly notes, a WIS. STAT. § 974.06 motion is not a vehicle to retry a case to a jury. A criminal defendant is constitutionally entitled as of right to a jury trial and, if convicted, a direct appeal. If he or she later seeks to collaterally attack the conviction on constitutional or jurisdictional grounds, a § 974.06 motion is appropriate. But key to any § 974.06 motion are sufficient, nonconclusory showings both as to why the issue was not raised in an earlier postconviction proceeding and why the claim has facial merit. These requirements are not optional and cannot be met through broad conclusions or by misstating evidence.

We express no opinion about who committed this crime: the jury has decided this question, and our review is confined to whether the claims before us entitle Avery to an evidentiary hearing.

What followed was a brief recap of how Avery might proceed in the absence of the evidentiary hearing he wishes to have — but again, the Court of Appeals suggested the path would likely be difficult.

Read the complete 49-page appellate opinion below: