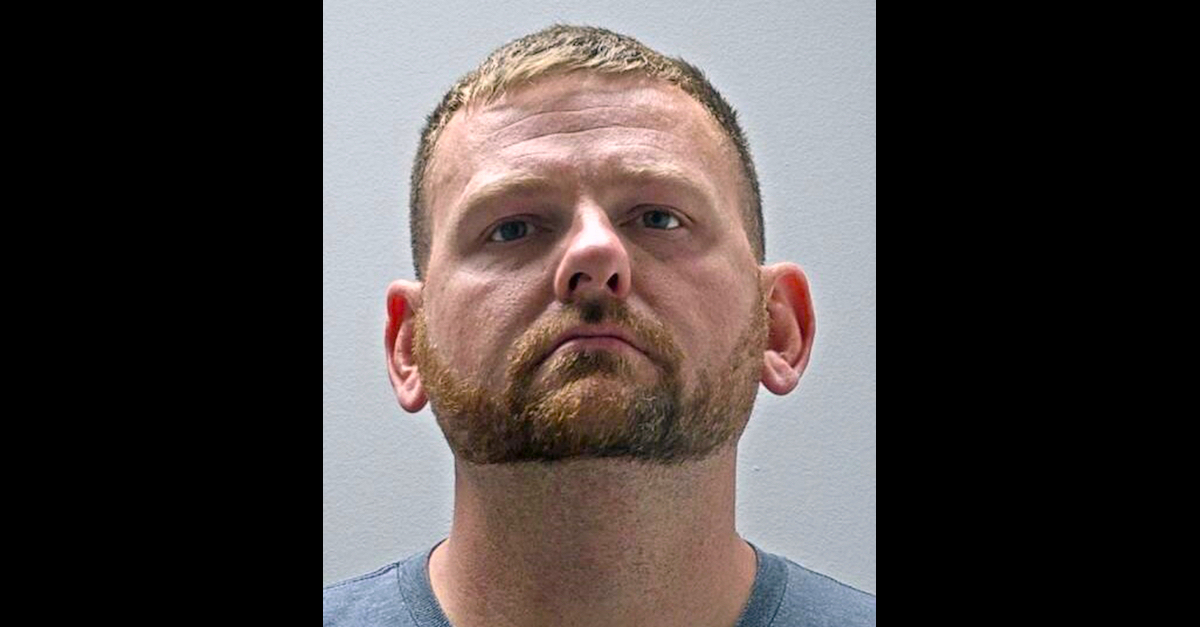

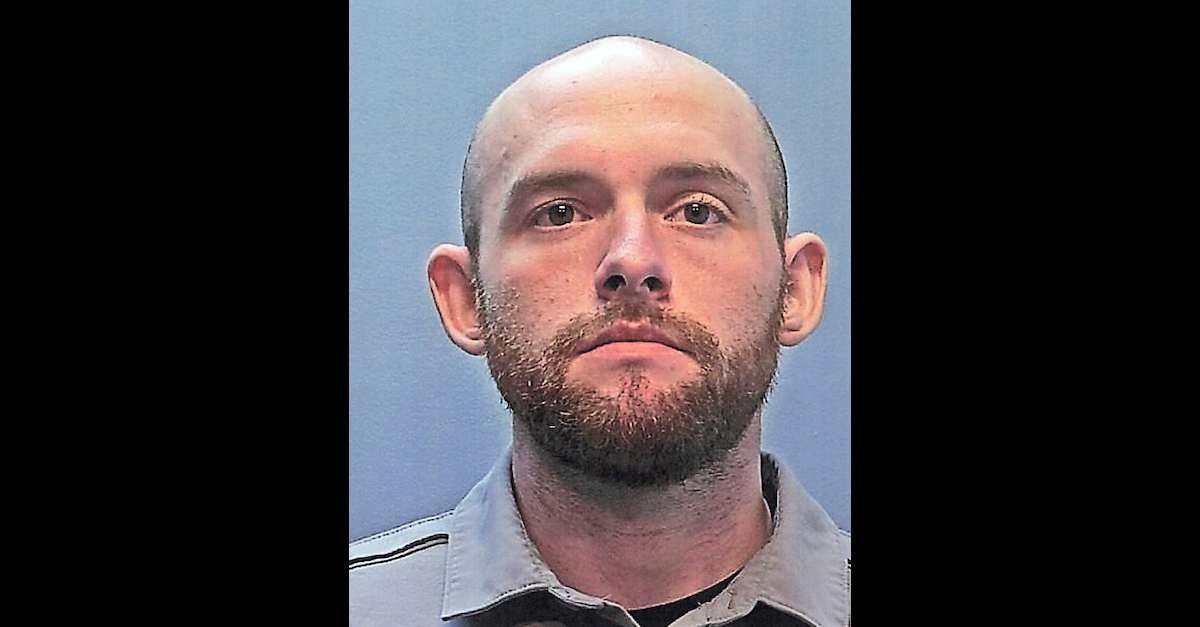

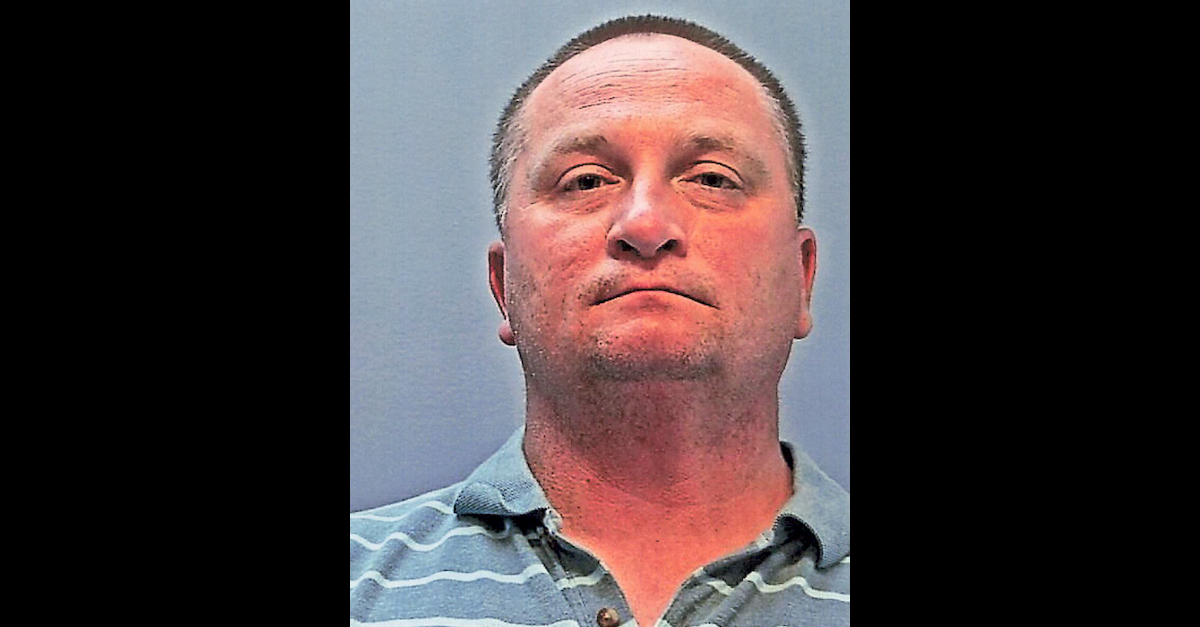

A mugshot array shows Aurora, Colo. Officers Randy Roedema and Nathan Woodyard, former officer Jason Rosenblatt, and paramedics Peter Cichuniec and Jeremy Cooper. All five are indicted in the death of Elijah McClain.

Booking photos have been released of the five men accused of criminally negligent homicide, manslaughter, and other charges in the death of Elijah McClain of Colorado.

As Law&Crime reported Wednesday, the Colorado Attorney General’s Office secured a 32-count grand jury indictment against the men. Three were police officers; two were fire department paramedics. All responded to a 911 call that suggested McClain — who was walking home from a convenience store — “look[ed] sketchy” but “might be a good person or a bad person.” The officers surrounded McClain, put him in a headlock, and ultimately killed him, the grand jury indictment alleges.

“Mr. McClain, who was frequently cold, was wearing a black mask and a jacket,” the indictment noted. The ski mask appears to be one of the reasons why a passerby summoned the police.

The named defendants are police officers Randy Roedema and Nathan Woodyard. Former police officer Jason Rosenblatt is also named. Jeremy Cooper and Peter Cichuniec are the fire department paramedics charged along with the current and former officers.

According to Denver NBC affiliate KUSA-TV, Woodyard, Rosenblatt, Cichuniec and Cooper “turned themselves in to the Glendale Police Department (GPD) Wednesday afternoon. They were processed on their warrants, posted bond, and were released, according to police.”

“Roedema turned himself in to the GPD Wednesday evening,” the television station reported. “He too was processed, posted bond and released.”

Randy Roedema

According to the indictment, Roedema “had been with the Aurora Police Department for five years.” He “previously spent six years with the Denver Sheriff’s Department[] and eight years of active duty service in the United States Marine Corps.”

Nathan Woodyard

The indictment says Woodyard had been on the Aurora police force “for two years and ten months, with five years of active duty service in the Marine Corps.”

Jason Rosenblatt

Rosenblatt “had been with the Aurora Police Department for two years,” the indictment continues.

Here’s what the men did, according to the indictment verbatim:

WOODYARD arrived first and ordered Mr. McClain to stop. WOODYARD did not see Mr. McClain with any weapons, but he noted a grocery bag and that, in his opinion, Mr. McClain was “suspicious.” Immediately after WOODYARD contacted Mr. McClain, ROSENBLATT joined WOODYARD, and the stop quickly turned physical. ROEDEMA later told investigators that in Aurora, as opposed to other police departments, they tended to “take control of an individual, whether that be, you know, a[n] escort position, a twist lock, whatever it may be, we tend to control it before it needs to be controlled.” The officers grabbed Mr. McClain’s arms then forcibly moved Mr. McClain over to a grassy area near where the officers first contacted Mr. McClain and pushed him up against the exterior wall of a nearby apartment building. ROEDEMA grabbed the grocery bag out ofMr. McClain’s hands and threw it to the ground. He did not examine the bag’s contents. The bag contained cans of iced tea. Mr. McClain was struggling as the officers attempted to restrain him. While Mr. McClain was pushed up against the wall and struggling, ROEDEMA told the other officers that Mr. McClain had reached for “your gun.” Neither ROSENBLATT nor WOODYARD knew whether “your gun” meant ROSENBLATTs or WOODYARD’s gun. ROEDEMA later said that Mr. McClain reached for ROSENBLATT’s gun. ROSENBLATT stated that he did not feel any contact with his service weapon.

The indictment then describes the “carotid control” hold and the “bar hammer lock” the officers allegedly — and admittedly — used on McClain.

Officers are instructed that to perform a carotid control hold an officer uses his or her bicep and forearm to apply pressure to the carotid arteries on the sides of a subject’s neck, thereby cutting off blood flow to the subject’s brain and causing temporary unconsciousness for the purpose gaining compliance or control. ROSENBLATT stated that he applied an unsuccessful carotid control hold to Mr. McClain, and WOODYARD then applied a carotid control hold that resulted in Mr. McClain going unconscious and snoring. Mr. McClain suffered bodily injury. He was was rendered unconscious, suffered hypoxia, and his physical and mental condition were impaired. The risk of hypoxia and cerebral hypoxia was exacerbated by applying two carotid control holds. ROEDEMA also placed Mr. McClain in a bar hammer lock. A bar hammer lock is a physical defensive tactic whereby a subject’s arm is held back behind their back to gain control of the subject. ROEDEMA stated that he “cranked pretty hard” on Mr. McClain’s shoulder and heard it pop three times. ROEDEMA, WOODYARD, and ROSENBLATT had all been trained that the carotid hold posed dangers and should never be administered more than once.

WOODYARD later told investigators that he was an arrest control instructor and had been serving in that role for about two months prior to the incident. ROEDEMA was also an arrest control instructor. ROSENBLATT had taken an in-service training that covered the carotid control hold on August 23, 2019, WOODYARD took the training on August 14, 2019, and ROEDEMA took the training on August 13, 2019.

Paramedics were called. The struggle ensued and is detailed in the indictment, which is embedded below.

Cooper and Cichuniec arrived at the scene. Cooper was described as “the medic in charge of the call and responsible for the medical decisions related to Mr. McClain as the patient.”

Jeremy Cooper

Cichuniec, meanwhile, “was in charge of the crew and was responsible for scene safety for both the patient and the emergency response personnel,” the indictment says.

Peter Cichuniec

The paramedics’ actions are described in the indictment in part as follows:

Upon their arrival at the scene, some members of the team from Aurora Fire Rescue were informed by a police sergeant that the carotid control hold had been applied to Mr. McClain, that he lost consciousness, and that he was “obviously on something.” In their interviews following the incident, COOPER and CICHUNIEC denied having knowledge that the carotid control hold had been applied to Mr. McClain. Officers also reiterated their belief that Mr. McClain was “definitely on something.” COOPER and CICHUNIEC stood near Mr. McClain but did not speak to him or ask him questions, though they did ascertain from officers that Mr. McClain spoke English.

[ . . . ]

COOPER and CICHUNIEC observed the physical restraint by police and watched ROEDEMA forcibly push Mr. McClain to the ground. Shortly after ROEDEMA forcibly pushed Mr. McClain to the ground, COOPER told police “We’ll just leave him there until the ambulance gets here and we’ll just put him down on the gurney.”

After approximately two minutes on scene, COOPER and CICHUNIEC both concluded that Mr. McClain was suffering from excited delirium. COOPER reached his diagnosis after receiving some information from officers and observing Mr. McClain for about one minute. Neither COOPER nor CICHUNIEC ascertained Mr. MecClain’s vital signs, nor did either of them talk to or physically touch Mr. McClain before diagnosing him with excited delirium.

The indictment says Cichuniec ordered Ketamine from a nearby ambulance and that a syringe containing 500 mg of the drug was then provided. According to the document, Cooper was to administer the drug.

“Yup, sounds good,” Rosenblatt said when the paramedics said they would administer the drug to McClain.

“Perfect, dude, perfect,” Roedema said.

The indictment says Cooper botched the injection by providing too much of the sedative:

A Falck Ambulance paramedic delivered the syringe to COOPER, who verified that it contained 500 mg of Ketamine. COOPER indicated that he intended to inject ketamine into Mr. McClain’s shoulder. ROEDEMA asked whether COOPER wanted 10 administer ketamine into Mr. McClain’s buttocks. ROEDEMA and other officers restrained Mr. McClain while COOPER injected the 500 mg of Ketamine into Mr. McClain’s right deltoid.

A correct dosage of Ketamine is calculated according to a patient’s weight, with 5 mg of Ketamine per kilogram of patient weight. COOPER said he estimated Mr. McClain’s weight to be approximately 200 pounds (90.7 kg). At that weight, in accordance with the standing order from their medical director, Mr. McClain should have been administered 453 mg of Ketamine. COOPER administered 500 mg of Ketamine. Mr. McClain actually weighed 143 pounds (65 kg) and as such his weight-based Ketamine dose should have been closer to 325 mg of Ketamine. The paramedics did not ask Mr. McClain how much he weighed and overestimated his weight by 57 pounds and administered a dosage that was appropriate for a patient who weighed 77 pounds more than Mr. McClain.

The indictment goes on to describe conversations among the men on the scene as to how to put McClain on a gurney and what to do next. Their actions resulted in the following, according to the document:

By the time he was placed on the gurney, Mr. McClain appeared unconscious, had no muscle tone, was limp, and had visible vomit coming from his nose and mouth. ROEDEMA said he heard Mr. McClain snoring, which can be a sign of a Ketamine overdose. Shortly after Mr. McClain was loaded into the ambulance, the paramedics discovered that Mr. McClain had no pulse and was not breathing. Paramedics performed CPR on scene, intubated Mr. McClain, and administered epinephrine directly into his shinbone. After a few minutes, Mr. McClain was transported to the University ofColorado Medical Center, and he eventually regained a pulse.

“Mr. McClain never regained consciousness,” the indictment says.

“Mr. McClain was a normal healthy 23-year-old man prior to encountering law enforcement and medical response personnel,” it later concludes. “A forensic pathologist opined that the cause of death for Mr. McClain was complications following acute Ketamine administration during violent subdual and restraint by law enforcement and emergency response personnel, and the manner of death was homicide.”

Read the indictment below:

[all mugshot images via the Glendale, Colo. Police Department]