ABA Legal Fact Check debuted in August and is the first fact check website focusing exclusively on legal matters. This article has been republished with permission.

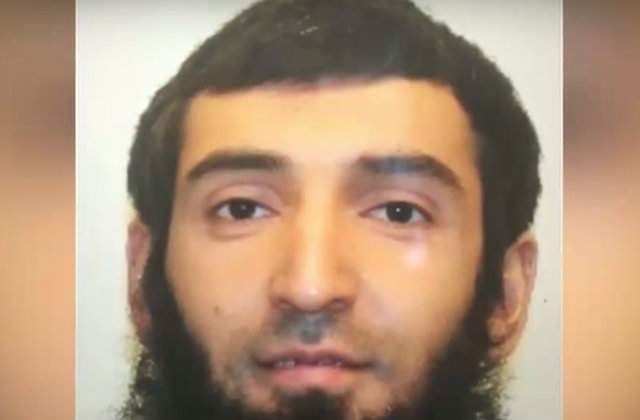

Shortly after Sayfullo Saipov, a non-citizen, was arrested for driving a truck killing eight people down a bike path on Oct. 31 in New York City, U.S. Sen. John McCain said: “The New York terror suspect should be held and interrogated — thoroughly, responsibly and humanely — as an enemy combatant consistent with the Law of Armed Conflict. He should not be read Miranda Rights, as enemy combatants are not entitled to them.” But the Trump administration has filed charges in federal civilian court against Saipov. What is the law?

Under the Military Commissions Act of 2006 (as modified in 2009), the U.S. president has the ultimate authority, as head of the executive branch of government, to decide whether Saipov, or any non-citizen suspected domestic terrorist, should be tried in military tribunals or in a civilian court. However, both the Obama and Trump administrations have relied on federal courts rather than military tribunals for every domestic terrorism case.

Two months after the 9/11 attacks, then-President George W. Bush issued a military order that called for the secretary of defense to detain non-citizens accused of international terrorism. Under the order, the defense secretary was charged with establishing military tribunals (also called military commissions) to conduct trials of non-citizens accused of terrorism either in the United States or in other parts of the world. To date, military commissions have not been used to try alleged domestic acts of international terrorism.

A military tribunal is different from a civilian criminal court. In a tribunal, military officers serve as jurors, under the guidance of a judge (who is most often a trained, experienced military judge). After a hearing, guilt is determined by a vote of the commissioners. Unlike with a criminal trial, the “jury” decision does not have to be unanimous. Moreover, the accused in a trial by military commission is not afforded many of the rights of a defendant in civilian court. In a military trial, for instance, evidence that was seized illegally might still be considered by the jury whereas it most likely would be excluded in clivilian court.

Bush’s directive marked a significant change in government policy: a military tribunal had not been used since World War II to try a foreigner for domestic terrorism. In 1942, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s proclamation that effectively detained, without civilian trial, eight captured German soldiers who had entered the U.S. on submarines on a sabotage mission. The high court determined the Germans were not entitled to habeas corpus proceedings to challenge their detention and found they “shall be subject to the law of war and to the jurisdiction of military tribunals.”

It took 64 years for the U.S. Supreme Court to decide another significant case related to military tribunals. After 9/11, as prisoners were sent to Guantanamo Bay, Congress passed the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005, which said “no court, justice or judge shall have jurisdiction to hear or consider” a habeas corpus petition of Guantanamo detainees. But in the 5-3 decision Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, the high court ruled that “the military commission at issue is not expressly authorized by any congressional act.” Rather, the court found Salim Ahmed Hamdan, a former driver and bodyguard for Osama bin Laden convicted by a military commission for providing material support for terrorism, was entitled to the full protections of the Third Geneva Convention. Within a year, however, the Military Commissions Act of 2006 was enacted and set out new procedures for handling non-citizen terrorism cases. Congress tweaked that law in 2009.

Now, nearly a decade later, the decision of where to try non-citizen domestic terrorists has become more of a political issue than a legal question. In the 2016 presidential campaign, then-candidate Donald Trump endorsed military tribunals over civilian courts for non-citizen terrorists. Senator McCain, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee and a former prisoner of war, backed that approach in his statement regarding Saipov after the Oct. 31 attack.

But to date, the Trump administration has deferred to a civilian line of prosecution, including filing federal charges against Saipov, who was in the U.S. on a diversity visa. This is consistent with the approach taken by President Obama, particularly after 2011 when Attorney General Eric Holder opted to prosecute Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, before a military commission. Holder faced intense public and congressional pressure to send Mohammed to Guantanamo Bay. Six years later, Mohammed is awaiting trial there.

Trump alluded to this reality when he tweeted on Nov. 2: “Would love to send the NYC terrorist to Guantánamo but statistically that process takes much longer than going through the Federal system. There is also something appropriate about keeping him in the home of the horrible crime he committed.”

Civilian prosecutions have generated successful results, as well. Human Rights First recently found that more than 620 individuals have been convicted in civilian courts on terrorism-related charges from 9/11 through May 30, 2017, while military commissions have convicted only eight — three of which have been overturned completely and one partially. A Justice Department release, updated about three years ago, suggested similar results.

Read more of ABA’s Legal Fact Check series here.

[Screengrab via Fox News]