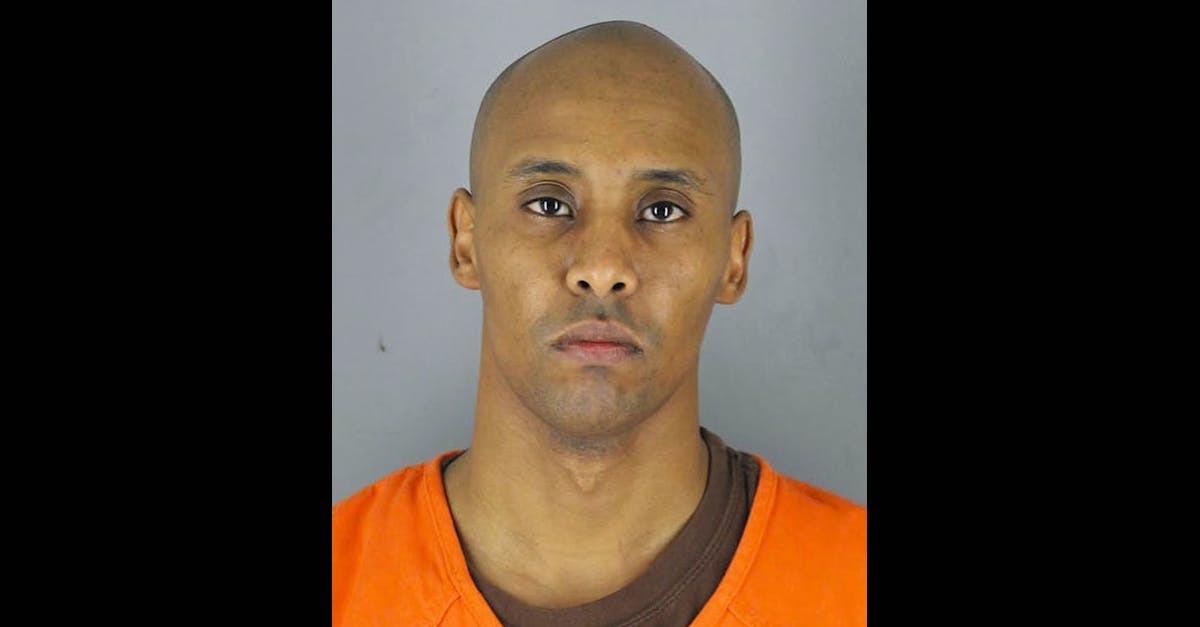

Mohamed Noor

The Minnesota Supreme Court on Wednesday rubbished the third-degree depraved-mind murder conviction of former Minneapolis police officer Mohamed Noor in the 2017 shooting death of Justine Ruszczyk (who was also known as Justine Damond). The high court’s ruling was unanimous.

A jury acquitted Noor of the more serious charge of second-degree murder. However, that same jury convicted Noor of both third-degree murder and the even lesser charge of second-degree manslaughter. Noor’s attorneys attacked the third-degree murder conviction — the highest remaining count — by claiming that there was no logical way the statute could apply to the facts of Noor’s case.

Facts

Noor and his partner Matthew Harrity responded to a 911 call Ruszczyk placed after hearing a woman screaming in an alley behind her home. The two officers drove down the alley but heard no signs of distress. Harrity stopped to let a bicyclist pass.

The state’s highest court further recapped the scenario as follows:

Harrity had “some weird feeling to [his] left side.” As Harrity began turning left, he heard something hit the car and “some sort of a murmur.” He exclaimed, “[O]h, shit or oh, Jesus,” and he immediately pulled his gun out of its holster. At this point, he could see that there was a “figure” outside his window, but he could not distinguish any details. Based on the unknown identity of the figure and the noise, Harrity thought “this could be a possible ambush or something.”

Harrity was still turning to his left when he heard a “pop” and “saw a flash.” His first instinct was to see if he had been shot because he did not know from where the shot came. Harrity did a “quick side eye” to his right and saw Noor with his gun drawn.

Noor testified that as soon as he entered the Code 4, he heard a “loud bang” on the driver’s side. At the same time, someone appeared outside the driver’s-side window. Harrity looked at the figure and screamed, “Oh, Jesus,” and immediately reached for his gun. Noor claimed that Harrity looked at him “with fear in his eyes” and that his gun appeared caught in its holster. Noor observed a blonde woman wearing a pink shirt. Noor testified that she began raising her right arm toward Harrity, so Noor rose from his seat, put his left arm across Harrity’s chest, fired one shot at the woman, and “[t]he threat was gone.” When they got out of the car, Noor realized that he shot an innocent person. Still, he testified that—in the moment—he shot out of concern for Harrity’s life.

The state’s high court said that it would “assume that there was no noise” because that appeared consistent with state’s closing argument and the jury’s assessment of the facts.

Issue

The legal issue on appeal was whether a Minnesota third-degree depraved-mind murder conviction can apply to a situation where a “defendant’s conduct is directed at the person who is killed.”

The question is prescient given the language contained within Minnesota’s third-degree murder statute.

Law Applied

The statute in question reads as follows (emphases added):

(a) Whoever, without intent to effect the death of any person, causes the death of another by perpetrating an act eminently dangerous to others and evincing a depraved mind, without regard for human life, is guilty of murder in the third degree and may be sentenced to imprisonment for not more than 25 years.

Procedural Posture

Defense attorneys for Noor argued that Minnesota’s third-degree murder statute was designed to apply to the unintended killing of an unintended third-party victim in a case where a defendant was acting dangerously toward a completely different and entirely separate person or group of people. Therefore, his attorneys argued, he could not be convicted of third-degree murder because he pointed his gun at, shot, and killed only Ruszczyk herself. Prosecutors countered that the third-degree murder statute could apply more broadly to a case where a defendant unintentionally killed the same exact person toward whom he exhibited eminently dangerous conduct and a disregard for human life.

A divided panel of judges on the Minnesota Court of Appeals — the state’s intermediate appellate court — held for the state and determined that the third-degree murder statute could apply where the defendant’s dangerously depraved conduct was aimed specifically at the ultimate victim (here, Ruszczyk). The court of appeals decision in Noor’s case caused a procedural hiccup in the factually unrelated case against Derek Chauvin in the killing of George Floyd, and it forced Chauvin’s trial judge Peter Cahill to ultimately reinstate the same exact charge — third-degree murder — against Chauvin.

Holding

The State Supreme Court settled the argument in favor of Noor. It characterized his argument as one which requires a “particular-person exclusion” in a third-degree murder analysis.

Rationale

After expending several pages reviewing the particulars of some “20 cases spanning . . . 163 years” of Minnesota jurisprudence, the state’s high court ruled as follows (citations omitted):

[O]ur precedent confirms that Noor is correct in arguing that a person does not commit depraved-mind murder when the person’s actions are directed at a particular victim. The particular-person exclusion is simply another way of saying that the mental state for depraved-mind murder is one of general malice. Under our precedent, general malice refers to conduct evincing indifference to human life in general and . . . does not refer to indifference “directed at the person slain.”

We reaffirm our precedent today and confirm that the mental state required for depraved-mind murder cannot exist when the defendant’s actions are directed with particularity at the person who is killed.

Later, the court put it this way in a footnote: “our precedent is clear that the State must prove general malice, a mental state that is incompatible with particular malice.”

In other words, the state couldn’t have it both ways: a defendant can’t be convicted of aiming at and killing a particular person (Noor’s manslaughter conviction) while also arguing he’s guilty under a statute which requires general malice toward other people in general (Noor’s third-degree murder conviction).

The Minnesota Supreme Court then slammed the state for twisting the holdings of several cases it relied upon to support Noor’s conviction.

Former Minneapolis police officer Mohamed Noor appears in a Hennepin County, Minn. jail mugshot.

“We are not persuaded,” the high court said. The justices said one of the cases cited “does not actually stand for the proposition cited by the State.” It also accused the state of “simply misread[ing]” another case and of “pluck[ing] a quoted sentence from that case without providing the proper context.

But the state did have one good case on its side, the Supreme Court said: State v. Mytych (1972). But the court overruled that case by ruling in favor of Noor.

“Mytych was clearly and manifestly wrong when it was decided, and it remains clearly wrong today,” the court said while jettisoning its legal rationale. The justices said it was “a complete departure from established precedent.”

And with that, the state had nothing left to stand upon.

The Supreme Court then dispatched with a few other arguments from the state in an attempt to keep the conviction intact based on particular jury instructions.

It went on to criticize the state for arguing that “the particular-person exclusion creates a ‘significant hole’ in Minnesota’s graduated statutory homicide scheme.” To fill it, the Supreme Court said the state invited it to “abandon . . . precedent and reinterpret the depraved-mind murder statute from a clean slate.”

The justices naturally scoffed at that suggestion (again, some citations omitted):

If there were, in fact, a “hole” in the statute, as the State argues, it would be the job of the Legislature to fill it. But as this case itself proves, there is no hole in Minnesota’s statutory regime. The parties agree that the evidence is sufficient to sustain Noor’s conviction for manslaughter. His death-causing action still results in criminal liability, and therefore there is no “hole” in the statutes in the truest sense of the word. To the extent that particularized, unintentional killings must be classified as murder—as the State contends—we have already said that second-degree felony murder . . . fills any meaningful gap created by the particular-person exclusion. See Nelson, 181 N.W. at 853 (holding that the defendant could not be guilty of depraved-mind murder but could be guilty of felony murder); Kopetka, 121 N.W.2d at 786 (same). The State chose not to charge Noor with that offense. The additional murder charge that the State did choose to bring—second-degree intentional murder—was rejected by the jury.

“In sum, the mental state necessary for depraved-mind murder, Minn. Stat. § 609.195(a), is a generalized indifference to human life and — based on our precedent — cannot exist when the defendant’s conduct is directed with particularity at the person who is killed,” the court ruled. “For the foregoing reasons, we reverse the decision of the court of appeals and remand to the district court to vacate Noor’s conviction for depraved-mind murder and sentence him on his conviction of second-degree manslaughter.”

The Supreme Court called Justine Ruszczyk’s death “tragic” and said she “sadly” died at the scene. But the justices pointed out that second-degree manslaughter is the more legally appropriate of the two punishments Noor faced.

Under Minnesota law, second-degree manslaughter is punishable by up to ten years in prison and a fine of up to $20,000. Third-degree murder is punishable by up to 25 years in prison and a fine of up to $40,000. Therefore, Noor’s possible sentencing range is significantly reduced when he returns to court to be re-sentenced. Noor was sentenced to serve twelve and a half years in prison in 2019 on the charge the Supreme Court threw out.

The case may have some repercussions in the more recent conviction of Derek Chauvin. Like Noor, Chauvin was also convicted of third-degree murder. Chauvin’s conviction for that particular crime may therefore no longer stand. However, Noor was acquitted of the more serious charge of second-degree murder. Chauvin was convicted of that more serious count. Both men were convicted of the lesser charge of second-degree manslaughter.

Read the full opinion below:

[image via screengrab from KARE-11/YouTube]