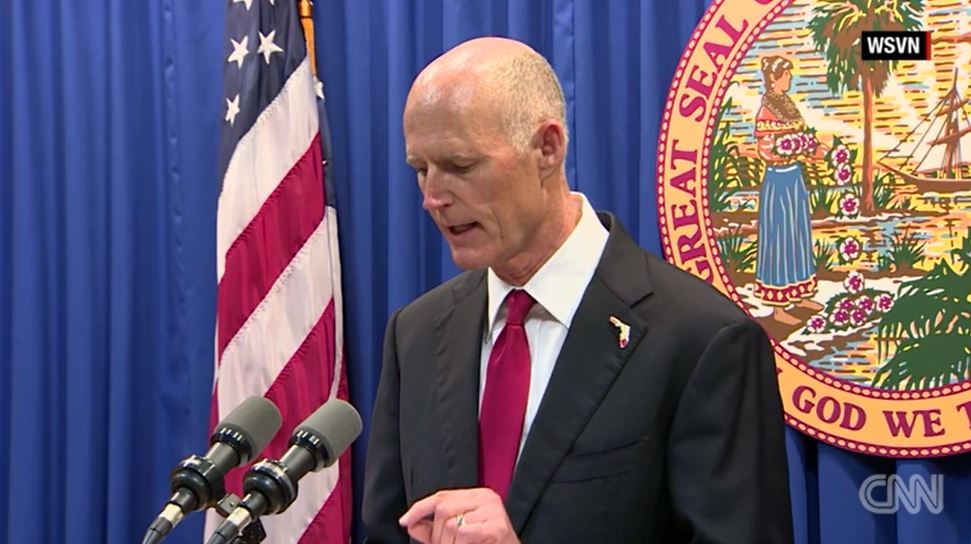

On Friday morning, Florida Governor Rick Scott proposed toughening up gun laws, school safety laws, and mental health laws in response to last week’s school shooting in Parkland, Florida, which left seventeen dead and fifteen injured.

In his speech, Scott addressed loopholes which failed to catch the alleged shooter, Nikolas Cruz:

Let’s review the warning signs here… he had 39 visits from police, his mother called him in, DCF investigated, he was kicked out of school, he was known to students as a danger to shoot people, and he was reported to the FBI last month as a possible school shooter. And yet, he was never put on the list to be denied the ability to buy a gun, and his guns were never removed from him.

Scott then described his solution to mental health issues under Florida’s mental health laws, known collectively as the Baker Act:

We will also strengthen gun purchase and possession restrictions for mentally ill individuals under the Baker Act. If a court involuntarily commits someone because they are a risk to themselves or others, they would be required to surrender all firearms and not regain their right to purchase or possess a firearm until a court hearing. We are also proposing a minimum 60-day period before individuals can ask a court to restore access to firearms.

We’ve added emphasis to the term involuntary commitments, because it’s very critical here. While many aspects of the governor’s plan would probably be very effective in stopping a mass shooting, what the governor is glossing over here is that involuntary commitment is near the tail end of the mental health process in Florida — and that’s where several loopholes exist.

As we previously explained in detail, the Baker Act begins with an examination, either voluntary or involuntary, which statistically does not very frequently lead to a commitment. Florida authorities average around 530 examinations each day of the year. Only 21% result in further treatment — including involuntary commitments and several other avenues of treatment. As we said the first time around, “critics might argue that this catch-and-release pattern could allow an adamant school shooter to be examined, but not committed, thereby slipping through the cracks of the system.” Some of the governor’s other proposals might further limit school shooters, but not mass shooters in general.

Whether involuntary commitment occurs depends on how detailed a person’s threat was articulated. In order to keep someone involuntarily committed, a court must agree that a patient legally qualifies. Among the legal qualifications for commitment are (1) a patient’s refusal to care for himself, or (2) a “substantial likelihood” that “serious bodily harm” would result “in the near future,” as “evidenced by recent behavior” from the patient.

That’s a lot to string together. Words, as one local attorney told us, are apparently enough to constitute a triggering “behavior,” but it seems under the letter of the law that imminence is a necessary requirement of the threat — it has to be likely in the near future.

Random threats, crazy remarks, and “maybe I’ll do this” statements might just not be enough to involuntarily commit someone, and that’s a problem under the current Baker Act. It forces courts to try to guess how soon someone might act, and the mental health community, as we have previously explained, is generally unwilling to make such predictions.

As such, the catch-and-release system remains in place, and the governor said nothing about changing it. Statistically, the governor’s plan to restrict gun rights after an involuntary commitment makes some sense but not a ton of sense given the other gaps in the system. Being involuntary committed means you’re already locked up against your will. It’s hard to go shoot up a public venue when you’re already locked up. Restricting gun rights after an involuntary commitment is smart, but questions remain as to whether it’s too hard to get someone involuntarily committed in the first place.

The governor’s full plan, as articulated Friday, might perhaps fill the gaps in other ways, but then again, it might not. Most of the plan involves school reforms, but not mass shooting reforms in general. The proposed “Violent Threat Restraining Order” kicks in after someone is already “mentally ill,” which takes us back to the issue above, or already “violent,” which might not catch everyone. The full plan is available here.