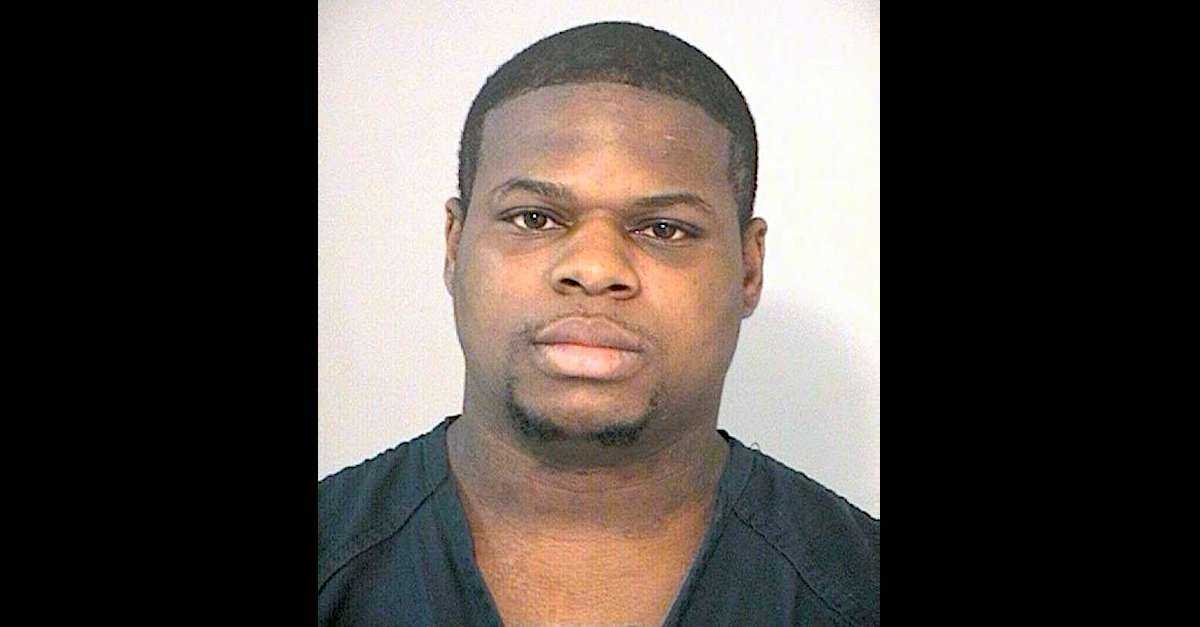

Terence Andrus

In a per curiam opinion, a majority of Supreme Court justices on Monday flipped a decision by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals to deny habeas corpus relief to Terence Andrus, a death row inmate convicted of killing two people in 2008 during a drug-fueled carjacking.

After noting Andrus’s trial attorney failed to present some mitigating evidence to the jury concerning the defendant’s upbringing at the hands of a mother said to have been given to drugs and prostitution, the Texas court ruled that Andrus did not deserve a new sentencing hearing because the offered mitigating evidence would not have likely kept him off death row. The majority of justices on the Supreme Court said that the Texas court didn’t properly explain their terse decision and thus needed to backtrack.

The unsigned 19-page Supreme Court opinion, by logical conclusion, was the work of a legally conservative/legally liberal cohort made up of justices John Roberts, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Brett Kavanaugh.

The court’s other legal conservatives rounded a bombastic dissent written by Samuel Alito and joined by both Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch. It accused the majority of being “selectively skeptical” about the two-pronged legal test of Strickland v. Washington, the seminal case which sets forth the legal standard for determining whether a verdict should be flipped due to poor performance by an attorney.

The majority ruled that the Texas appeals court needed to firm up its analysis. The Supreme Court thus sent the case back — a remand — but did not reverse the judgement. The ruling merely vacated the Texas court’s decision.

“[T]he record makes clear that Andrus has demonstrated counsel’s deficient performance under Strickland,” the majority wrote in reference to the first prong of the analysis. “[B]ut that the Court of Criminal Appeals may have failed properly to engage with the follow-on question whether Andrus has shown that counsel’s deficient performance prejudiced him.” Because of that, the majority on the Supreme Court sent the case back to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals.

Here’s how the Supreme Court recapped the relevant legal standard in Strickland (citations omitted):

To prevail on a Sixth Amendment claim alleging ineffective assistance of counsel, a defendant must show that his counsel’s performance was deficient and that his counsel’s deficient performance prejudiced him. To show deficiency, a defendant must show that “counsel’s representation fell below an objective standard of reasonableness.” And to establish prejudice, a defendant must show “that there is a reasonable probability that, but for counsel’s unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different.”

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals failed on the second prong of the analysis, the Supreme Court said, while noting that a concurring opinion in the Texas case did contain such an analysis. “[T]he Court of Criminal Appeals did not analyze Strickland prejudice or engage with the effect the additional mitigating evidence highlighted by Andrus would have had on the jury,” the high court said.

Justice Alito flipped out at the way the majority read the lower court’s opinion (some citations and punctuation omitted):

The Court clears this case off the docket, but it does so on a ground that is hard to take seriously. According to the Court, “it is unclear whether the Court of Criminal Appeals considered Strickland prejudice at all.” But that reading is squarely contradicted by the opinion of the [Texas] Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA), which said explicitly that Andrus failed to show prejudice: “Andrus fails to meet his burden under Strickland . . . to show by a preponderance of the evidence that his counsel’s representation fell below an objective standard of reasonableness and that there was a reasonable probability that the result of the proceedings would have been different, but for counsel’s deficient performance.”

[…]

How, then, can the Court get around the unmistakable evidence that the CCA decided the issue of prejudice? It begins by expressing doubt about the meaning of the critical sentence reproduced above. According to the Court, that sentence “does not conclusively reveal whether [the CCA] determined that Andrus had failed to demonstrate prejudice under Strickland’s second prong.” It is hard to write a more conclusive sentence than “[Andrus] fails to meet his burden under Strickland v. Washington to show by a preponderance of the evidence . . . that there was a reasonable probability that the result of the proceedings would have been different, but for counsel’s deficient performance.” Perhaps the Court thinks the CCA should have used CAPITAL LETTERS or bold type. Or maybe it should have added: “And we really mean it!!!”

Such temper tantrums are rare in Supreme Court opinions.

Alito believes the Texas court’s decision should be read in finality: Andrus failed to prove prejudice and, therefore, ought to be executed by the state.

The majority’s ruling suggested that six justices were concerned enough about Andrus’ defense attorney’s conduct to order a more thorough review below, but not concerned enough to flip the case in a wholesale manner and order a new sentencing hearing for the defendant. As recited by the majority, Andrus’ trial attorney presented no case whatsoever during the guilt phase of the trial and even conceded Andrus’ guilt. The trial attorney “informed the jury that the trial would ‘boil down to the punishment phase,’ emphasizing that ‘that’s where we are going to be fighting,'” the Supreme Court quoted him as saying.

Things didn’t get better. During the punishment phase of the case, Andrus’s attorney gave no opening statement. The state’s three-day case (at this stage of the trial) “put forth evidence that Andrus had displayed aggressive and hostile behavior while confined in a juvenile detention center; that Andrus had tattoos indicating gang affiliations; and that Andrus had hit, kicked, and thrown excrement at prison officials while awaiting trial,” the Supreme Court said. “The State also presented evidence tying Andrus to an aggravated robbery of a dry-cleaning business.” Yet the defense “raised no material objections to the State’s evidence and cross-examined the State’s witnesses only briefly.” The defense called Andrus’s mother but “did not reveal any difficult circumstances in Andrus’ childhood.” The mother testified that the defendant had no access to drugs or pills and that she would have counseled him had she caught him with illicit substances. Andrus’ biological father, who had not seen the defendant in “more than six years,” also took the stand; he had himself been in and out of prison.

The Supreme Court majority said this is what was really going on in the background and what should have been argued at trial:

Death-sentenced petitioner Terence Andrus was six years old when his mother began selling drugs out of the apartment where Andrus and his four siblings lived. To fund a spiraling drug addiction, Andrus’ mother also turned to prostitution. By the time Andrus was 12, his mother regularly spent entire weekends, at times weeks, away from her five children to binge on drugs. When she did spend time around her children, she often was high and brought with her a revolving door of drug-addicted, sometimes physically violent, boyfriends. Before he reached adolescence, Andrus took on the role of caretaker for his four siblings.

When Andrus was 16, he allegedly served as a lookout while his friends robbed a woman. He was sent to a juvenile detention facility where, for 18 months, he was steeped in gang culture, dosed on high quantities of psychotropic drugs, and frequently relegated to extended stints of solitary confinement. The ordeal left an already traumatized Andrus all but suicidal. Those suicidal urges resurfaced later in Andrus’ adult life.

During Andrus’ capital trial, however, nearly none of this mitigating evidence reached the jury.

The Supreme Court said that Andrus’s attorney’s performance was so perplexing that the trial judge even asked him if he was going to call more witnesses; he then decided to call several experts — and then Andrus himself. Even then, the testimony was not thorough, the majority said:

Contrary to his mother’s depiction of his upbringing, [Andrus] stated that his mother had started selling drugs when he was around six years old, and that he and his siblings were often home alone when they were growing up. He also explained that he first started using drugs regularly around the time he was 15. All told, counsel’s questioning about Andrus’ childhood comprised four pages of the trial transcript. The State on cross declared, “I have not heard one mitigating circumstance in your life.”

Andrus’s attorney gave no explanation for failing to dig further into his client’s life during state-level appeals hearing.

In his dissent, Alito said the majority “never acknowledges the volume of evidence that Andrus is prone to brutal and senseless violence and presents a serious danger to those he encounters whether in or out of prison,” and instead “says as little as possible about Andrus’s violent record.”

Alito would have interpreted the Texas court’s decision to keep Andrus on death row as definitive and final.

Read the opinions below.

TERENCE TRAMAINE ANDRUS v. TEXAS by Law&Crime on Scribd

[Images via Alex Wong/Getty Images and mugshot]

Editor’s note: this piece has been updated.