Attorney Eric Nelson (L) and his client Derek Chauvin (R).

Hennepin County District Court Judge Peter Cahill on Thursday morning ruled that Derek Chauvin, one of four former Minneapolis police officers charged in the alleged murder of George Floyd, must again face a third-degree murder charge.

The ruling came on the third day of jury selection in Chauvin’s trial. The other three officers are scheduled to be tried together in August in a proceeding separate from Chauvin’s case.

The decision comes after both Chauvin and prosecutors wrestled the question of whether a Feb. 1 Court of Appeals opinion in a different case, State v. Noor, should be interpreted as to allow prosecutors to re-file third-degree murder charges against Chauvin. Cahill ruled that Noor should not affect Chauvin’s trial under the rationale that Noor could be further appealed to the Minnesota Supreme Court and ultimately reversed. The Minnesota Supreme Court subsequently decided to hear arguments in Noor in June 1 — a potential signal that it was unhappy with the lower Court of Appeals decision.

Because Cahill rubbished Noor while deciding that Chauvin should not again face a third-degree murder charge, prosecutors appealed on the narrow question of whether the Noor opinion became binding upon trial court judges like Cahill the moment it was issued. The Court of Appeals agreed with prosecutors on March 5 that Noor became binding precedent the minute it was filed and therefore must control the relevant question in Chauvin’s case. On March 10, the state Supreme Court refused to take up the matter after Chauvin’s attorneys asked for additional clarity.

Those procedural moves set the stage for — and all but foretold — Cahill’s Thursday morning ruling.

The underlying legal question, which the Supreme Court has not yet settled, involves conflicting interpretations of Minnesota’s third-degree murder law. The statute says a defendant who intends “to effect the death of any person” but who ultimately “causes the death of another” person “by perpetrating an act eminently dangerous to others . . . may be sentenced to imprisonment for not more than 25 years.”

Law&Crime added the boldface type above to highlight the legal issue at play in both Noor and Chauvin. According to the defense in both cases, the statute only applies when the ultimate victim who died was not the initial focus of harm. Cahill and the defense both crystalized the issue as whether a so-called “single-person rule” is wrapped up within the third-degree murder statute. For now, Cahill was required to follow the now-binding Court of Appeals decision which held that the statute applies to a single-person victim.

Chauvin’s defense attorney, Eric Nelson, argued Thursday that Noor’s case was unlike Chauvin’s, despite the fact that both cases involved Minneapolis police officers.

“That’s about where the similarities end,” Nelson said.

In other single-person-rule cases, he argued, “there’s some sort of an instrumentality that is used — a gun or a car, generally speaking. Those items could be viewed as inherently dangerous” to others under the plain language of the statute.

Cahill said he agreed that Noor was procedurally and factually different from Chauvin’s case. In Noor, an officer fired his gun past his partner on the force and ultimately killed a woman. Cahill suggested Noor could have been settled as such and without invoking the single-person rule; however, he noted that the Court of Appeals saw it differently.

To the contrary, Chauvin’s case involves no weapons or items which could have caused danger to others and was therefore factually distinct.

Attorney Neal Katyal, who is one of several attorneys handling the Chauvin case on behalf of the state, argued that adding the third-degree murder was “a very straightforward decision” which “reflects the gravity of the offenses.”

Nelson further argued that Chauvin was being subjected to an unconstitutional ex post facto interpretation of the law. That provision of the U.S. Constitution says defendants cannot be convicted under laws which are passed after an alleged crime occurred. Katyal responded that the ex post facto clause can only applies to new legislature from retroactively applying to old crimes despite Nelson’s citation of case law which suggested it can also be triggered by novel interpretations of statutes already on the books. (In the case Nelson cited, the court ruled that no violation occurred because the new interpretation of the law was “foreseeable.”)

While ruling against Chauvin, Cahill shared several harsh words over the way the Court of Appeals handled the matter.

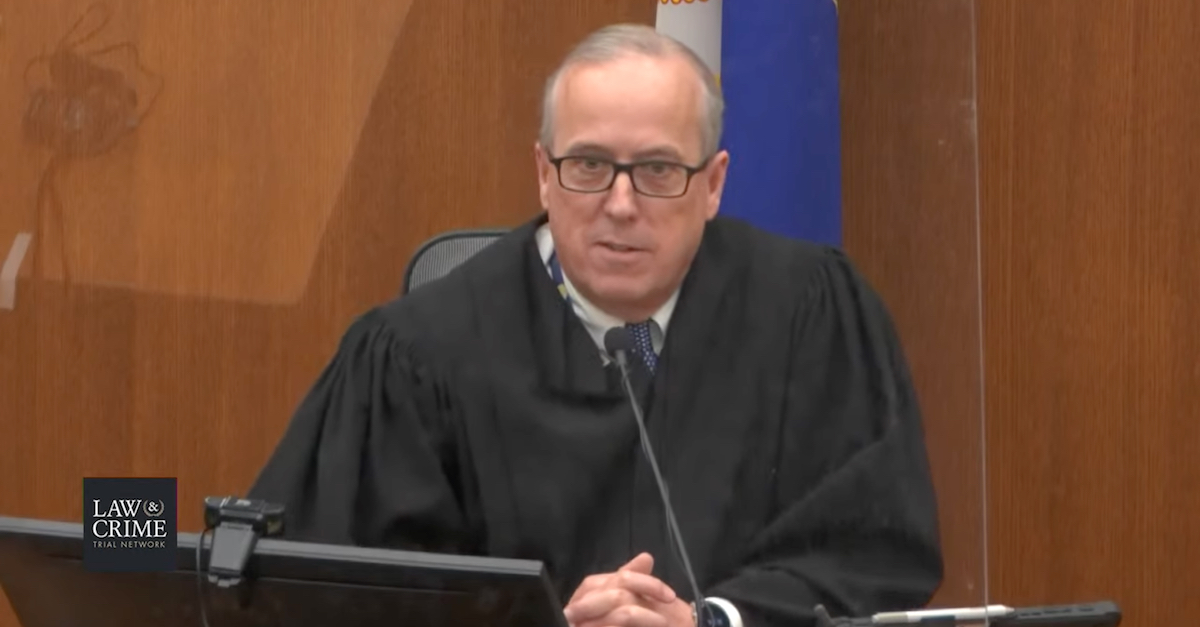

Judge Peter Cahill

“The Noor opinion came out, and it was very clear that I disagreed with it; said so; denied the [original] motion [to reinstate third-degree murder] because of my disagreement — but not without first checking to see if I was duty bound to follow it as precedent,” Cahill said. “Now, based on the defendant’s appeal, the Court of Appeals had made it very clear, yes, I was bound from the moment the moment the opinion was filed. And I accept that. I even agree with the [March 5] decision in State v. Chauvin that their opinions have precedential value immediately.”

Cahill continued his explanation:

I want to explain why, because I did not believe so before. My concern was how the Court of Appeals got to that position. They stated in their analysis that the “plain language” of the rule says that precedential opinions took immediate effect. That implies that this court disregarded “plain language” in the rules or, at worst, was too lazy to look up the rules. Neither is the case. Upon reading the Noor opinion, realizing its application to this case, this court immediately turned to the rules to look for plain language as to when opinions that are marked as precedential have, in fact, that precedential effect. We found silence, not “plain language”. I think the Court of Appeals reaches too far by saying there’s “plain language” in the rules. There is silence.

I think what the Court of Appeals ha[s] inferred form the silence is that opinions take immediate effect when filed. I accept that because of my second reason: despite my disagreeing with them that the “plain language” is there, it is my belief and analysis that courts have inherent judicial authority to say when their opinions have effect. If the Court of Appeals believes that their precedential opinions — they get to decide when they’re going to file it; how they’re going to file it; whether it’s an order opinion or more extensive — that is entirely — that is in the rules. There is plain language about that. But, clearly, every court has inherent judicial authority to decide when their opinions will be effective.

Because the rules were silent, in this court’s view, our next step is to look for case law. And we found Collins, which said it does not have precedential value until judgement is entered. The state has successfully argued to the Court of Appeals that that was dictum in Collins . . . and I accept that. That is their ruling. And, based on that, I think the inherent judicial authority — there is that authority to make that decision and to say ‘when we file a precedential opinion, it has immediate effect.’ I accept that now as a rule of law promulgated by the Court of Appeals due to its inherent judicial authority to make such pronouncements. Because no pronouncement was made to such effect by any court that I was able to find before the Chauvin opinion was filed, that is why I said that the precedential value did not attach until judgement because that is what Collins said. District courts, I think, are more at risk to start calling Supreme Court pronouncements dictum and refusing to follow it because of that.

Cahill then turned to the core question of whether third-degree murder applies to Chauvin’s case:

I am granting the motion because although these cases are factually different, that is Noor and the case before us, I don’t think it’s a factual difference that weighs in favor of denying the motion to reinstate because of the language of Noor. Noor is very clear: when intent is directed at a single person — this is a legal principle that they have established now as precedent — then third-degree may apply. Single acts directed at a single person fall within the gambit of murder in the third degree, and as I said, that was part of their holding, it is not dictum. Accordingly, I am bound by that. I have to apply the rule. Even though they are factually different, I have to follow the rule the Court of Appeals has put in place, specifically that murder in the third degree applies even if the person’s intent and acts are directed at a single person.

The Supreme Court, of course, may flip that analysis, but for now, Chauvin must live by it.

Cahill then recapped the matter:

My ruling both in the fall and lately in denying the motion to reinstate was based on a legal principle alone . . . it was the facts of the case that this appeared to be an act directed towards a single person, and on that legal principle of the ‘single-person rule,’ this court granted a motion to dismiss for [lack of] probable cause and denied the motion to reinstate. But now that the . . . Court of Appeals has said in a precedential opinion specifying the ‘single-person rule’ applies to third-degree murder, I feel bound by that and I feel it would be an abuse of discretion not to grant the motion.

Cahill then said this charge did not blindside Chauvin’s defense “out of left field.” Therefore, it was not unfair to add third-degree murder unless the defense could prove it was unfairly prejudiced by the move — which he suggested the defense most likely was not given the reality that the charge was hanging over the case for months.

In total, here are the charges Chauvin now faces: (1) unintentional second-degree murder on top of intentional third-degree felony assault, punishable by up to 40 years in prison; (2) third-degree murder, punishable by up to 25 years in prison; and (3) second-degree manslaughter, punishable by up to ten years in prison and a $20,000 fine. In other words, the state finally secured every single count it originally sought back in June 3, 2020.

Watch the hearing below:

[image via the Law&Crime Network]

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]