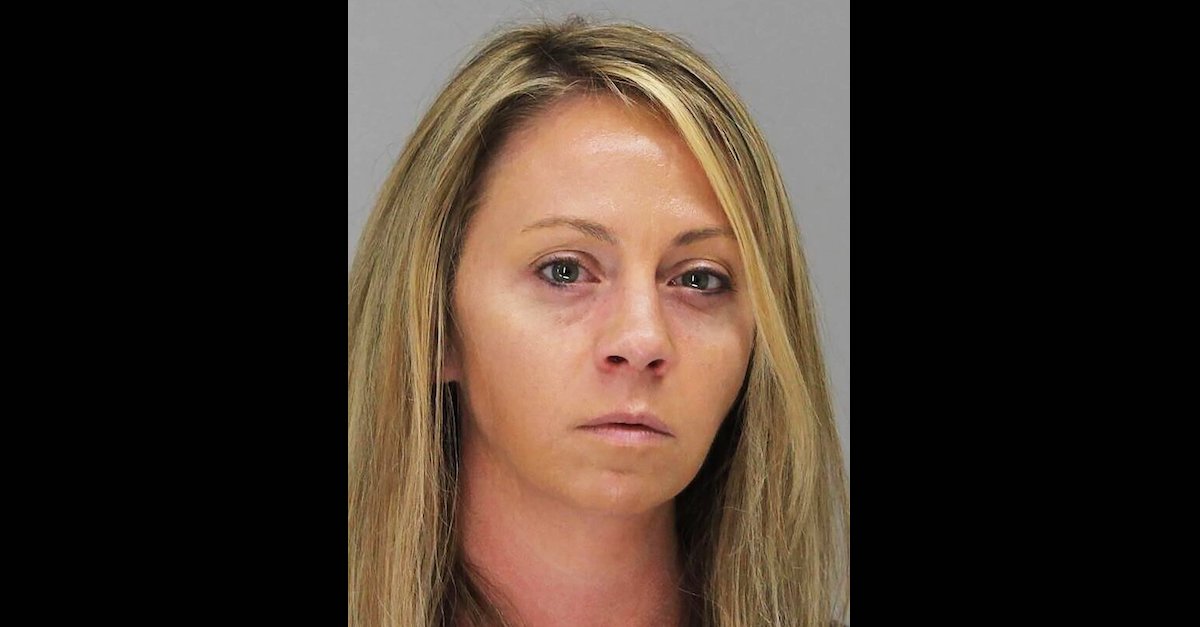

Amber Guyger appears in a Dallas County Sheriff’s Department mugshot dated October 1, 2019.

An intermediate Texas appeals court on Thursday upheld former Dallas police officer Amber Guyger’s murder conviction in the shooting death of Botham Jean, 26.

Guyger, now 32, testified at trial that she accidentally drove to the wrong floor of her apartment complex while she was distracted by a phone call and entered Jean’s apartment thinking that it was her own. When Guyger saw Jean inside his own apartment, Guyger drew her service weapon and shot him dead. A jury convicted Guyger of murder; a judge sent her to prison for 10 years. Guyger’s expected release date is September 29, 2029, but she is eligible for parole in Sept. 2024, according to jail records.

Guyger argued that her actions constituted a mistake of fact (for being in the wrong apartment) and self defense (for shooting who she assumed was an intruder in her own apartment). She asked the state’s Fifth District Court of Appeals to either (1) rule that the evidence was insufficient to support her conviction, or (2) to acquit her of murder, convict her of criminally negligent homicide (which carries a might lighter sentence), and to order a new sentencing hearing.

The state argued that Guyger’s attempt to mix mistake of fact and self defense was legally erroneous.

Legal Sufficiency

The Court of Appeals first ruled that the evidence was sufficient to support Guyger’s conviction.

Citing case law, the court said “the relevant question is whether, after viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the verdict, any rational trier of fact could have found the essential elements of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt.”

The court said in rather swift fashion that the evidence was, indeed, rational.

“Guyger testified she intended to kill Jean when she shot him,” the court’s opinion says. “In addition, the State introduced evidence that Jean was a living human being—an individual — whose death was caused by the gunshot wound inflicted by Guyger. Accordingly, legally sufficient evidence supports the jury’s murder verdict.”

The court then turned to Guyger’s twin defenses: mistake of fact and self defense. The burden of proof in those defenses is as follows: “Guyger bore the burden of producing evidence supporting each of her defensive issues, while the State retained the burden of persuasion to disprove those defenses beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Botham Jean appears in an undated portrait released by Harding University in Arkansas.

Mistake of Fact

The court of appeals skewered Guyger’s attempt to suggest that her jury should have been allowed to consider a “mistake of fact” defense. The precise legal meaning of the phrase “mistake of fact” is not the same as the common or lay application of the term. Mistake of fact can only be used to suggest Guyger never formed the necessary culpable mental state to have committed the crime charged. In this case, the requisite mental state is intent: the question is whether Guyger had the intent to kill Jean. And the Court of Appeals noted that Guyger admitted she did, indeed, intend to kill when she pulled the trigger. Because she admitted intent, she cannot rationally argue mistake of fact, the court rationed.

The court suggested that Guyger was attempting to shoehorn the legally distinct defense of justification into a mistake-of-fact analysis. The court’s opinion shakes down the analysis at length:

Guyger’s brief highlights “48 distinct factual points” which she contends show her “clear mistake of fact” and her reasonable conduct under the circumstances. Those points include the following: her fatigue; talking on the phone when she mistakenly parked on the unmarked but wrong floor of the garage; missing visual cues distinguishing the fourth floor from the third; the unlatched door that she was able to open even though her key fob did not unlock it; the dim lighting in the apartment and floor plan identical to her own apartment; and her training to shoot to kill when she believed she was in mortal danger. None of these points, however, speak even remotely to Guyger’s intent to kill. Instead, each fact relates only to whether she was justified in defending herself because she believed she was in her own apartment and that Jean was an intruder. Thus, rather than conclusively proving her mistake of fact defense, the evidence here demonstrates the mistake of fact instruction was not warranted because no evidence negated Guyger’s intent to kill Jean when she shot him. We conclude the hypothetically correct jury charge should not have included a mistake of fact instruction. Accordingly, the mistake of fact issue is not part of our analysis of the sufficiency of the evidence to support Guyger’s murder conviction.

The court then turned to the issue of justification — here, that’s self defense.

Botham Jean appears in a 2014 portrait released by Harding University, his alma mater.

Self Defense

The court said Guyger’s reliance on this defense mechanism was also misplaced. A valid self-defense claim would have “required Guyger to produce evidence that she reasonably believed deadly force was immediately necessary to protect herself from Jean’s use or attempted use of unlawful force.”

Here, Guyger again attempted to intertwine the mistake-of-fact analysis into a self-defense claim. The court swept away that argument as such:

Guyger relies on her mistaken belief that she was in her own apartment to support the reasonableness of her belief that Jean posed an imminent threat. Mistake of fact, however, plays no role in self-defense—the former addresses Guyger’s culpable mental state; the latter addresses the circumstances and reasonableness of Guyger’s conduct. Guyger’s argument thus bootstraps mistake of fact to reach the [Texas Penal Code] section 9.32(b) presumption of reasonableness. As discussed below, we conclude sufficient evidence defeated the presumption and also supports the jury’s rejection of this defense because a reasonable jury could have determined Guyger’s belief that deadly force was immediately necessary was not reasonable.

The Court of Appeals noted that under Texas law, deadly force is presumed to be reasonable when an actor uses it against an intruder who “unlawfully and with force entered, or was attempting to enter unlawfully and with force, the actor’s occupied habitation.” And here, the “habitation” wasn’t Guyger’s; it was Jean’s. Therefore:

The jury’s rejection of Guyger’s self-defense argument finds ample support in the record. It is undisputed that Jean was in his home and was not attempting to unlawfully enter Guyger’s apartment. Further, Guyger admitted that she could have taken a position of cover and concealment while she called for backup rather than shooting Jean. This admission was buttressed by the testimony of Officer Lee. In his testimony, Lee told the jury that if he came across a burglar while off duty and was safely able to take a position of cover and concealment, he would use his take-home radio to call for help rather than call 911. He explained the radio connected directly to dispatch and thus provided faster help since the 911 call would be delayed by the transfer to dispatch. He also testified that, when responding to a burglary call in which he had not yet entered the premises, for his safety and that of the person inside, his training mandated taking a position of cover and concealment rather than entering alone. In a burglary situation in which he had already entered the premises but had the option of safely repositioning to cover and concealment, he would likewise do so rather than shooting the intruder. He also testified that, if there were a burglar or other intruder in his home, he would allow that person the opportunity to surrender. He explained that in intense situations where another person posed a threat, he focused on the suspect’s hands to determine whether the suspect held an item that could cause bodily harm, and in those situations it was important to determine where the suspect’s hands were.

A further analysis by the court noted that additional witness testimony suggested Guyger fired without ordering Jean to show his hands.

Criminally Negligent Homicide

Finally, the Court of Appeals rubbished Guyger’s attempt to suggest that a lesser charge was the only appropriate charge in her case. The Court said that Guyger focused on the circumstances and facts of the shooting to make her argument for a lesser charge and failed to look at her mental state. The focus should have been on Guyger’s “intent to kill Jean by shooting him,” the Court said — and, again, Guyger admitted the requisite mental state necessary for a murder conviction. Criminally negligent homicide is, as its name suggests, a crime involving mere negligence.

Law&Crime previously explained in detail the case presented by each side when a panel of three judges heard oral arguments in the matter.

The opinion is marked as unpublished, meaning it carries no precedential value but may be cited in future cases as carrying no true legal weight.

Read the full opinion below: