Travis McMichael, Gregory McMichael, and William Bryan are seen in jail booking photos.

Attorneys for the three defendants charged in connection with the alleged murder of Ahmaud Arbery, 25, on Thursday sparred with prosecutors about admissible evidence and with the press about whether certain portions of the jury selection process would be closed to the public.

Travis McMichael, Gregory McMichael, and William “Roddie” Bryan are each charged with one count of malice murder, four counts of felony murder, two counts of aggravated assault, one count of false imprisonment, and one count of engaging in a criminal attempt to commit a felony.

The Thursday hearing followed an avalanche of court filings from both sides in the case over the course of the last month. Some of the state’s filings have sought additional time for closing arguments, to block testimony from neighboring District Attorney George Barnhill (who thought the charges weren’t warranted), to bar the defense from arguing that Georgia’s former citizen’s arrest law was repealed specifically because of this case, to prevent the defense from turning the “beyond a reasonable doubt” legal standard into a mathematical calculation, to admit defendant Bryan’s video of the shooting into evidence and to play it during opening statements, to prevent speculative testimony, and to admit into evidence defendant Gregory McMichael’s personnel files from the Glynn County District Attorney’s Office and from the Georgia Peace Officers Standards and Training Council under limited circumstances (such as impeachment, if necessary). The state has also sought to prevent the jury from hearing about threats lodged against various individuals in connection with Arbery’s death.

The defendants have sought to introduce evidence of Arbery’s mental health. They’ve also sought to prevent alternate jurors from learning they’ve been tagged as alternates until all the evidence has been presented, and they’ve asked the court to closely monitor so-called “rehabilitation” questions asked of potential jurors during voir dire. Such questions are an attempt to ascertain whether a juror can put aside previously held views about the case to deliver a fair verdict, and they have become serious sticking points in other recent high-profile cases, such as the Derek Chauvin trial in Minnesota.

Here are some of the issues argued on Thursday.

Questioning Jurors

Attorneys for the McMichaels requested the option to question some jurors in chambers — outside the purview of the public and of the press — given the sensitivity of the case and of some of the questions the parties may wish to ask members of the jury panel. A consortium of media organizations objected to that move, and the defense shot back by arguing that the press’s request to brief the legal issues and then argue them in full would offend the defendants’ constitutional rights — in part because of the back-and-forth nature of written arguments.

“This ordinary briefing schedule to me sounds like 30 days [for one side] and 30 days [for the other side], and 15 days to reply — we still have a speedy trial demand pending,” one defense attorney for William “Roddie” Bryan said Thursday. “We don’t want the media inadvertently — however with the best of intentions — to create a briefing situation for us that’s going to interfere with the trial in this case in October.”

“I think there should be a way to resolve those issues by consent today,” the attorney suggested.

But Tom Clyde, an attorney for the media organizations, said that the press’s position is that closing off part of voir dire would be in “conflict with well-established constitutional law.”

Evidence Issues

Considerable time was spent hashing out various motions in limine to determine whether certain evidence will or will not be admissible at trial.

Prosecutors said forensic analyses on computers and cell phones were sent to the defense teams yesterday.

A fourth supplemental witness list of “over 120 people” was also sent by the state to the defense. Prosecutors said the voluminous list was necessary so that they are not caught having to, for instance, call a police officer to testify who’s “not on the list.” But they added that they would compile a “pared down” witness list for the state’s case in chief.

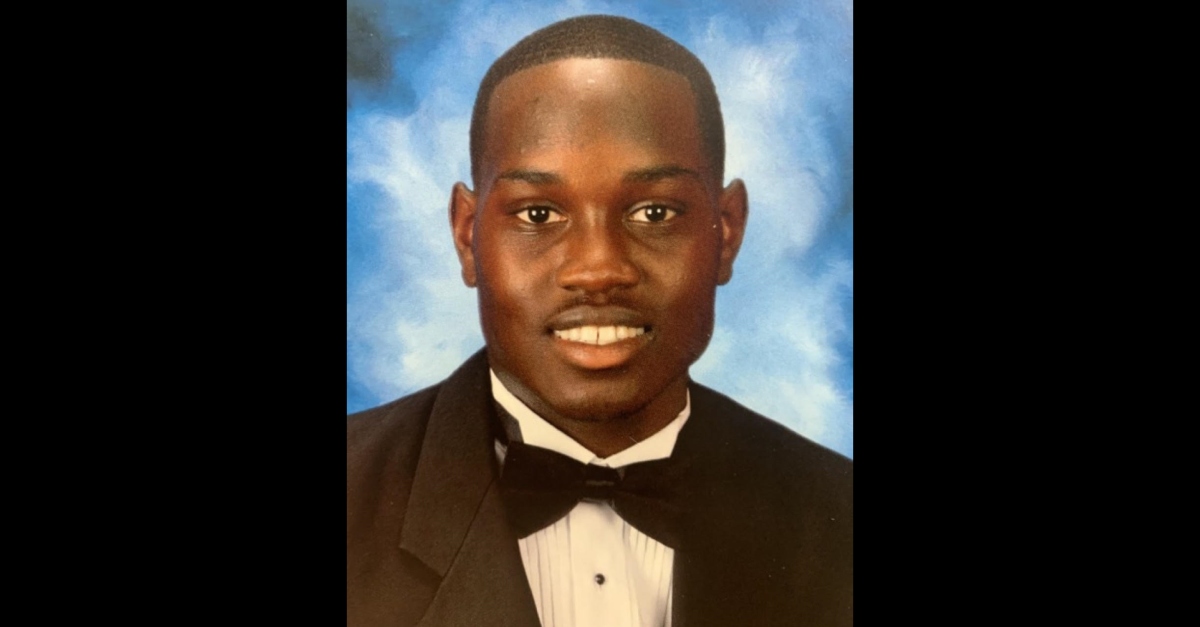

Ahmaud Arbery. (Image via Attorney Benjamin Crump.)

The state accused the defense of violating an earlier order of the court to provide prosecutors with a list of witnesses they intend to call.

“The state has absolutely no witness list from any of these defendants,” one prosecutor said. “They have violated your Oct. 30th order,” that same prosecutor told the judge.

One of the defense attorneys said “90%” of their witnesses are also on the prosecution’s list.

“What is holding us up,” the defense said, was a yet-to-be decided court ruling on issues involving 404(b) evidence — that’s evidence of a person’s prior crimes, wrongs, or other bad acts — and on the aforementioned mental health matters. The defense noted that a mental health expert would likely be called as a witness.

Prosecutors later rubbished defense attempts to prevent recordings of some of the defendants’ own police interviews from being seen by the jury.

“My intention here is to keep, basically, this from the closing argument: ‘you didn’t even get, jury, to hear their actual statements,'” a prosecutor argued.

In the absence of being able to use the actual recordings, the prosecutor said she feared having to put a detective on the stand to testify as to a defendant’s statements — which were Mirandized, videotaped, and audiotaped — and then suffer defense attacks that the recordings themselves weren’t played in court.

That would be unfair, the state said, when it was the defense which sought to ban the recordings from being played.

“The state doesn’t want the defense to argue as if the state’s keeping something from the jury when they’re the ones with the Bruton objection to everything coming in,” the prosecutor said (referencing Bruton v. United States, a 1968 U.S. Supreme Court case). “So, it may or may not occur . . . they can criticize us for [an alleged] lack of evidence all day long, but specifically, this sort of, ‘you didn’t get to hear the statements,’ when they’re the ones who want the statements redacted, I think is unfair.”

One of the defense attorneys countered that it would be improper for any of the defense attorneys — each defendant has his own, of course — as an “officer of the court” to perpetrate such a sleight-of-hand argument.

Prosecutor Linda Dunikoski elsewhere argued that witnesses should not be allowed to testify that the defendants were making a valid or an attempted citizen’s arrest of Arbery.

“There’s just no way to have a neighborhood testify that it was on edge or a neighborhood had a feeling” that crime was afoot in the area, Dunikoski said. “And this sort of drum beat that the neighborhood feeling justified a witch hunt would be inappropriate.”

Several of the defense attorneys shot back by saying that the defense was allowed to, in their view, present virtually any excuse necessary for the shooting and killing of Arbery.

“The fact that we have the opportunity to present evidence in support of any theme and theory that we choose is simply the law,” said defense attorney Laura Hogue, who represents Gregory McMichael.

Kevin Gough, a defense attorney who represents Bryan, said all of the defendants had been victims of theft.

The defense has suggested that the McMichaels “had a valid reason to pursue Arbery, thinking he was a burglar, and that Travis McMichael shot him in self-defense as Arbery grappled for his shotgun,” the Associated Press said in a broad summary of the various recent arguments.

Length of Closing Argument

Under Georgia court rules, each side of a felony case punishable by death or life in prison is allotted two hours for closing arguments. In the Ahmaud Arbery case, the state is asking for more time due to the multiple legal issues presented and the multiple defendants.

“That is a lot to argue in two hours for the state,” one prosecutor told the judge — all while noting that the state’s time must be split between a closing argument in chief and a subsequent rebuttal.

“The jury will then have six hours” of the arguments from the defense after the state’s initial argument before the state is allowed to circle back and conclude the matter.

The state always gets the first and last word in a criminal prosecution because the state has the burden of proof.

“I’m asking for three hours out of an abundance of caution,” the prosecutor said. “I truly hope not to take that entire three hours and potentially maybe not even take up the full two hours depending on how the course of the trial goes.”

Attorney Kevin Gough makes a point while his client, William “Roddie” Bryan (seated, in white shirt), looks on. (Image via the Law&Crime Network)

One defense attorney said the “set of facts” were “finite” in this case and did not warrant a three-hour argument. The defense said that a six-hour closing argument spread across all three defendants would be a signal that the defense had collectively “done something wrong” during the preceding portions of the proceeding.

Another defense attorney said he feared both an increased time frame for the state and that the scheduling of the arguments could be hijacked to benefit the state. For instance, the state could give its closing argument before the jury took a lunch break or recessed for the evening. The defense feared the chance that the jury could mull the state’s arguments all night before hearing from the defense — and the longer the state’s arguments, the longer the chance the state could strategically structure its case to split the clock in its favor.

All three defendants have pleaded not guilty.

A trial is scheduled for Oct. 18th.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]