The Trump administration will end the Obama-era policy known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Effective tomorrow, no new applications will be accepted. Two small caveats offer rays of hope to some DACA recipients (Dreamers): (1) any Dreamers whose permits are set to expire before March 5, 2018 will be allowed to apply for a two-year renewal; (2) Congress could decide to protect the program within the six-month timeframe set by the White House.

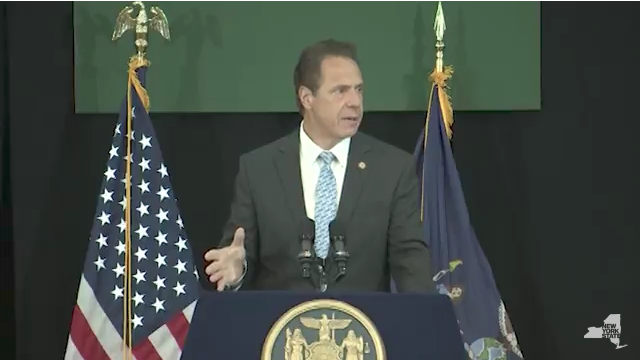

Anticipating the termination of DACA, multiple Democratic politicians and immigrants’ rights organizations have hinted at or promised litigation in order to protect Dreamers generally and DACA in particular including New York Governor Andrew Cuomo. But those lawsuits are likely to fail due to the nature of DACA itself. The program was originally outlined by President Barack Obama via an executive action which is now being undone by another executive action. The basis for which any pro-DACA party might sue upon is thin and any attempts to clear legal hurdles are likely to be bogged down in procedural minutiae.

What follows is an analysis explaining why any of these anticipated lawsuits are little more than doomed PR attempts–and poor vehicles to protect the rights of young undocumented immigrants.

DACA, Briefly

DACA was enacted via a memo sent by then-Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, Janet Napolitano to three other agency heads on June 15, 2012. The original memo is available here. To clarify, DACA was never the result of an executive order. Rather, it was a re-shuffling of immigration enforcement priorities classified as a memorandum which outlined the exercise of DHS’ prosecutorial discretion.

In other words, DACA was simply an understanding between the federal government and a small class of undocumented immigrants (who met certain qualifications) that they were at the bottom of the list of people to be deported.

That understanding also came with a two-year promise in the form of a permit which allowed Dreamers to more easily access certain benefits–like work authorization and drivers licenses–but did not actually confer any “substantive right, immigration status or pathway to citizenship.” All told, DACA has prevented the deportation of roughly 790,000 undocumented immigrants who came to the United States as children.

This program was never challenged in the courts, but ten Republican-controlled states promised to issue such a legal challenge if Trump did not make good on his campaign promise to end DACA. Today’s phasing out of the program is Trump delivering on that promise–and the states have already begun to drop their legal threats. As mentioned above, however, Democratic-controlled states and immigrants rights organizations will soon file lawsuits of their own, but those lawsuits will likely fail.

Legal Hurdles

While there was no direct legal challenge to DACA itself, in 2014, a lawsuit filed by 25 Republican-controlled states killed a planned expansion of DACA and a program for parents of Dreamers known as DAPA.

Their lawsuit prevailed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas and went up through the court system before stalling at the U.S. Supreme Court (by way of a tie vote) which left the lower court ruling intact. In that lawsuit, Texas and other states won a standing challenge initiated by the Obama administration largely due to the processing fees associated with drivers license applications. There, the court said, Texas was footing (part of) the bill for a surge in license applications, thus they were able to satisfy the most heavily disputed aspect of a standing analysis: injury.

The prevailing anti-DAPA lawsuit is important to note because it offers a preview of what arguments are likely to be used in forthcoming litigation–and how some of those arguments might play out–but it was wrongly decided. It was decided incorrectly on multiple counts, but the real battle is likely to be waged on the issue of standing. Therefore, standing is the first major question for the pro-DACA lawsuits and also the Trump administration’s first line of defense.

Under the U.S. Constitution, Article III standing requires: (1) injury; (2) causation; and (3) redressability. Because the potential plaintiffs are unlikely to sustain an initial finding of injury, the other two prongs of a standing analysis are unnecessary.

In a lawsuit intended to salvage DACA, immigrants’ rights advocates and opportunistic politicians like Andrew Cuomo might feasibly claim some sort of administrative hiccups–and associated costs–will ensue from phasing out DACA, but this wouldn’t likely rise to the level of injury required to survive a standing challenge. That’s because phasing out DACA will not require any affirmative steps be taken by the states and this is what the Trump administration will almost certainly argue if and when pro-DACA suits make it to court.

The Obama administration effectively argued this same point when they unsuccessfully tried to defend DAPA (and DACA expansion) in the aforementioned case in front of Judge Andrew S. Hanen. Hanen disagreed and by way of extremely convoluted mental gymnastics, he produced an order in direct tension with the Supreme Court’s decision in Arizona v. United States (which more or less affirmed the supremacy of federal law viz. immigration).

Indeed, as mentioned above, Hanen got it wrong. The Obama administration was correct then and the Trump administration will be correct now and in the future. In other words, Trump’s lawyers will use the same argument that Obama’s lawyers used–in service of exactly the opposite goal. At root, this is what the ensuing lawsuits are all about–federal supremacy–but a lot of the action happens around the procedural issue of standing.

Alternatively, some pro-DACA states could argue some sort of loss in GDP or taxable income, etc. But such arguments have fallen flat before the courts since 1927. There are other forms, of standing, however–and it is entirely possible that a sympathetic judge or court could stretch precedent beyond recognition to advance litigation further for a showdown on the Supreme Court. In fact, that’s entirely likely–none of the courts are actually apolitical–but will only produce fleeting wins.

There may be minor court victories for pro-DACA lawsuits, perhaps for those filed directly by Dreamers, but such victories are likely to be short-lived, because those results will at least create full-on tension with Hanen’s decision. That means a circuit split is in the cards and the Supreme Court will be forced to weigh in on the subject and make a final decision.

Why the Supreme Court allowed the original lower court ruling to stand when in sharp contrast to precedent was likely a purely political choice (undergirded by the absence of a ninth justice), but in any event, it’s hard to see how the Supreme Court finds a way to reconcile the Arizona opinion with the assuredly incoming standing challenges lobbed at any and all pro-DACA lawsuits.

TL;DR–

When the original DAPA lawsuit was punted on by the Supreme Court, that was a defeat for Obama. But had the Supreme Court not treated the issue like a political football, it’s hard to see how the federal government could have lost a case that’s essentially about the primacy of federal law vis-à-vis immigration. And, it’s exceedingly difficult to see how the calculus changes now that Neil Gorsuch is on the bench.

The executive branch has wide latitude in using prosecutorial discretion. Obama understood this and used it–both as the Deporter-in-Chief (remember: this is the same president who deported more people than nearly all of the other presidents combined) and as the man who tried to protect Dreamers. Trump has just as much prosecutorial discretion as Obama and can use it to both supplant his predecessor as Chief Deporter or show some heart. Of course, it’s obvious which direction Trump is headed, and these lawsuits may yet slow those deportations down, but they alone are not the salve to stop them.

[image via screengrab]