Former Vice President Mike Pence on Wednesday failed to address several key portions of the U.S. Constitution while arguing that several proposed sweeping changes to federal election law would be unconstitutional if passed.

“Leftists not only want you powerless at the ballot box, they want to silence and censor anyone who would dare to criticize their unconstitutional power grab,” Pence wrote for The Daily Signal, a conservative website which is the “multimedia news outlet” of the Heritage Foundation. (Pence is now a Heritage Foundation distinguished visiting fellow.) His overall piece, “Election Integrity Is a National Imperative,” tiresomely grinds the grievance that 2020 presidential election was “marked by significant voting irregularities and numerous instances of officials setting aside state election law.” Pence fears that a federal election reform bill known as the “For the People Act” will even further usurp the power of state governments to control elections; he believes the bill therefore violates Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution. But his interpretation of the nation’s supreme legal document in search of the classic state vs. federal debate ignores many key portions of the document itself.

As Pence noted, Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 (the “Presidential Electors Clause”) says in part that “[e]ach State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors” who in turn go on to select the U.S. president. As such, Pence used the word “unconstitutional” three separate times to describe the federal “For the People Act.”

His analysis ended there. Accordingly, Pence ignored this portion of Article II, Section 1, Clause 4: “[t]he Congress may determine the Time of chusing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.”

That language connects to another provision of another part of the Constitution which Pence also ignored.

As University of Texas law professor Steve Vladeck pointed out, Article I, Section 4, Clause 1 (the “Elections Clause”) explicitly allows Congress to directly control the way states handle some elections matters. That section of the Constitution states that “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof, but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators” (emphasis added).

Both Article I and Article II allow Congress to peg federal elections in general on the same calendar date, and the relevant language of Article I allows Congress to override state legislatures in determining the “manner” by which an election for federal legislators shall unfold. Two federal statutes, 2 U.S.C. § 7 and 3 U.S.C. § 1, have since 1875 and 1948 respectively scheduled the elections of both legislators and presidents on “the Tuesday next after the first Monday in November.” Simply put, in modern times, presidents are not specially elected on different dates using different procedures from those applied to and selected for elections for federal legislators.

Pence might have proposed that it is it wrong to draw a connection between the elections procedures outlined in Article I and Article II, but he didn’t—possibly for good reason. Perhaps he could have said that those provisions are separate and distinct for an elementary reason: Article I pertains to the legislature and Article II pertains to the executive. Therefore, he might have said that textualists and other Constitutional purists might reasonably assume a harsh separation between the elections procedures associated with the legislative and the executive branches of government. Perhaps, per the concomitant language of each Article of the Constitution, Congress could not override state legislatures in election matters involving the executive but could override election matters involving the federal legislature. However, such a harsh separation—had Pence actually suggested it—would have failed to acknowledge other realities.

First, it would have failed to acknowledge the originalist fear of election malfeasance by unscrupulous state actors. Second, it would have failed to acknowledge that Congress can under Articles I and II set the legislative and the executive elections on the same exact calendar date—which it has. Third, it would have failed to acknowledge that Pence’s own small-government constituents would struggle to swallow the bureaucracy and the expense necessary to maintain two parallel yet likely incongruent election regimes on the same exact day. Fourth, it would fail to acknowledge the reality that two parallel yet opposite election regimes would result in nothing short of lunacy.

By lunacy, here’s how the facts would play out under this possible interpretation which—again—Pence completely ignored. Congress could allow, under Article I elections involving the legislature, all the things Pence says he hates: “universal mail-in ballots, early voting, same-day voter registration, online voter registration, and automatic voter registration for any individual listed in state and federal government databases, such as the Department of Motor Vehicles and welfare offices, ensuring duplicate registrations and that millions of illegal immigrants are quickly registered to vote.” Yet under Article II, state legislatures could foreclose all those possibilities when it comes to the election of the president. People would be forced to cast one vote one way and another vote the other way. People might be registered to vote for federal senators and representatives but not be registered to vote for president. The incongruence would be stark.

Pence didn’t discuss this logical upshot of his proposal because he ignored key portions of the Constitution while arguing in favor of state control over presidential elections.

He also didn’t discuss several other critical authorities. For instance, the Supreme Court of the United States opined as recently as 2015 that state governments, when left to their own devices, can do things that are very dangerous to democracy.

“The dominant purpose of the Elections Clause [of Article I], the historical record bears out, was to empower Congress to override state election rules, not to restrict the way States enact legislation,” wrote Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission. The case held that Arizona could constittuionally use an independent commission to map out district lines for federal representatives. The move, which wrestled control away from the state legislature, did not offend the U.S. Constitution’s “animating principle . . . that the people themselves are the originating source of all the powers of government.”

Justice Ginsburg quoted Arizona v. Inter Tribal Council of Arizona, Inc. to remind everyone that the Elections Clause “was the Framers’ insurance against the possibility that a State would refuse to provide for the election of representatives to the Federal Congress.” Such antiquated fears of banning elections altogether or of refusing to seat representatives have modern corollaries, the majority noted.

Ginsburg then penned a lengthy history lesson concerning the federal government’s role in elections. She referred liberally to Founding Father Alexander Hamilton’s The Federalist No. 59, to the writings of Founding Father James Madison, and to other influential thinkers (some internal punctuation and citations omitted):

The Clause was also intended to act as a safeguard against manipulation of electoral rules by politicians and factions in the States to entrench themselves or place their interests over those of the electorate. As Madison urged, without the Elections Clause, “whenever the State Legislatures had a favorite measure to carry, they would take care so to mould their regulations as to favor the candidates they wished to succeed.” Madison spoke in response to a motion by South Carolina’s delegates to strike out the federal power. Those delegates so moved because South Carolina’s coastal elite had malapportioned their legislature, and wanted to retain the ability to do so. The problem Madison identified has hardly lessened over time. Conflict of interest is inherent when “legislators draw district lines that they ultimately have to run in.”

Arguments in support of congressional control under the Elections Clause were reiterated in the public debate over ratification. Theophilus Parsons, a delegate at the Massachusetts ratifying convention, warned that “when faction and party spirit run high,” a legislature might take actions like “making an unequal and partial division of the states into districts for the election of representatives.” Timothy Pickering of Massachusetts similarly urged that the Clause was necessary because “the State governments may abuse their power, and regulate . . . elections in such manner as would be highly inconvenient to the people.” He described the Clause as a way to “ensure to the people their rights of election.”

While attention focused on potential abuses by statelevel politicians, and the consequent need for congressional oversight, the legislative processes by which the States could exercise their initiating role in regulating congressional elections occasioned no debate. That is hardly surprising. Recall that when the Constitution was composed in Philadelphia and later ratified, the people’s legislative prerogatives — the initiative and the referendum — were not yet in our democracy’s arsenal. The Elections Clause, however, is not reasonably read to disarm States from adopting modes of legislation that place the lead rein in the people’s hands.

Again, Ginsburg ruled with other members of the court’s left and center wings (Kagan, Breyer, Sotomayor and Kennedy) that the State of Arizona could allow an independent commission, rather than the state legislature itself, to map out congressional districts. Roberts, Scalia, Alito, and Thomas dissented. The majority ruling logically rationed that the U.S. Constitution did not fully allow state legislatures to have the final word over federal elections matters.

Though the Supreme Court’s opinion applied to Article I, it carries strong lessons against voter suppression which are easily connected to Article II — especially given the textual reality that Congress can set the elections both for legislators and for presidents on the same exact date.

A full debate about such issues requires an analysis of the full United States Constitution—not just the portion Pence chose to cite.

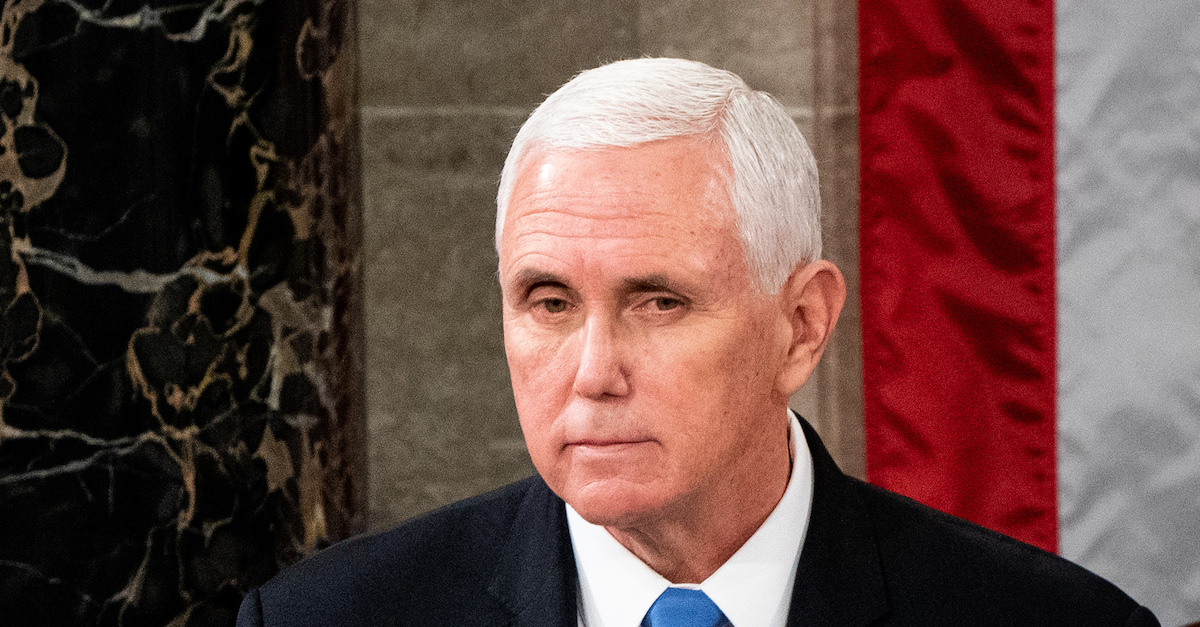

[Photo by Erin Schaff/Pool/Getty Images]

Editor’s note: this piece has been updated for clarity.