A federal judge in Iowa has dismissed with prejudice a defamation lawsuit filed by Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Calif.) against Hearst Magazine Media, Inc., and Ryan Lizza, a journalist and political analyst.

The case revolved around a Sept. 30, 2018 article published in Esquire magazine entitled “Milking the System.” An online version of the piece is alternatively entitled “Devin Nunes’s Family Farm Is Hiding a Politically Explosive Secret.”

Among the story’s claims is that a farm operated in California by various members of the Nunes family was subsequently moved to Iowa and that it ultimately, like many midwestern dairies, used “undocumented labor.” Per the online version of the report:

According to two sources with firsthand knowledge, NuStar did indeed rely, at least in part, on undocumented labor. One source, who was deeply connected in the local Hispanic community, had personally sent undocumented workers to Anthony Nunes Jr.’s farm for jobs. “I’ve been there and bring illegal people,” the source said, asserting that the farm was aware of their status. “People come here and ask for work, so I send them over there.” When I asked how many people working at dairies in the area are documented citizens, the source laughed. “To be honest? None. One percent, maybe.”

Nunes sued and claimed that a series of statements in the report had defamed him personally — even though the report made it clear that Devin Nunes himself “had no financial interest in his parents’ Iowa dairy operation.”

Here’s how U.S. District Judge C.J. Williams retold some of the history of the litigation:

Plaintiff [Nunes] challenges eleven statements in the Article and alleges the Article implies plaintiff conspired with his family and others to cover up NuStar’s use of undocumented labor, and thus, defamed him. Plaintiff also claims that Lizza conspired with others to promote the Article and further defame plaintiff. Plaintiff demanded defendants retract the Article. Defendants refused, and plaintiff filed this suit.

Among the Nunes claims was “defamation by implication,” which occurs “when the defendant either juxtaposes a series of facts to imply a defamatory connection between them or omits facts to create a defamatory implication.”

Hearst and Lizza moved to dismiss the case on three grounds. First, they claimed none of the individual statements in the article were defamatory on their own — or, in other words, nothing was actionable as a matter of law. Second, they claimed the article was not defamatory as a whole because it did not survive the implication analysis outlined briefly above. Third, they claimed that Nunes could not prove “actual malice.” That’s the First Amendment term of art which requires a public figure — such as a congressman — to prove that the defendants’ either (A) knew their statements were false before publishing them, or (B) published with reckless disregard of whether the statements were true or not. (Actual malice does not measure dislike or hatred: it measures the defendants’ attitude toward the truth.)

In a 48-page opinion which contains several pages of highly technical cogitations involving conflicts of law and the implications of reading California’s Anti-SLAPP statute into the framework of federal civil procedure, Judge Williams tossed the case with prejudice — meaning Nunes cannot refile it.

Here’s one of the things Nunes messed up: his “brief largely ignores the individual statements he identifies and instead focuses on the implication of the Article as a whole,” the judge said. (Keep in mind that the judge in May had schooled Nunes’s lawyers on how to do their jobs.)

What follows in the opinion (on pages 23 onward) is a dairylicious takedown of Nunes’s claims — line by line, word by word, blow by blow, with precise citations to previous cases which back up the judge’s decision. Here is a sampling of how the judge addressed and refuted Nunes’s claims:

These statements are not actionable for several reasons. First, portions of the statements refer to plaintiff’s family members [or others] and those portions are not “of and concerning” plaintiff. To any extent that plaintiff’s family moving to Iowa is “of and concerning” plaintiff, it is admittedly true, and not defamatory because it does not tend to harm plaintiff’s reputation.

Statements to the effect plaintiff has a secret or concealed his family’s move are also not defamatory. It is not defamatory to alleged [sic] plaintiff concealed or kept secret his family’s move to Iowa. See Wyo. Corp. Servs. v. CNBC, LLC, 32 F. Supp. 3d 1177, 1187 (D. Wyo. 2014) (finding that statements that plaintiff created shell corporations “to conceal ownership” were not defamatory); Cannon v. Bee News Pub. Co., 8 F. Supp. 154, 156-57 (D. Neb. 1933) (statement that plaintiff was married in a “secret wedding” was not defamatory because plaintiff “had a right, if [he] saw fit, to withhold the knowledge” of the wedding).

On and on the judicial takedown of Nunes goes. The judge found other statements in the article were “protected opinion” — “‘rhetorical hyperbole’ . . . thus protected by the First Amendment.” Others were “nonactionable opinions.”

Some of the statements Nunes complained about were later apparently admitted by him to be true, the judge noted.

As to the core complaints about immigrant labor, the judge said as follows:

The Article as a whole makes clear plaintiff has no financial interest in NuStar and that plaintiff’s family members, not plaintiff, operate NuStar. Thus, no reasonable person could interpret this statement as implying that plaintiff himself was using or benefiting from immigrant labor, documented or otherwise.

In other words, Devin Nunes has no legitimate gripe.

More broadly, as to the rights of the press and of Nunes’s thought process in making his claims:

Plaintiff’s complaint relies on “naked assertion[s]” and “labels and conclusions” which are devoid of “further factual enhancement,” to establish actual malice. Plaintiff cannot rely on general assertions and must plead facts to support a finding of actual malice. Although it is difficult for politicians like plaintiff to plead actual malice against the media while still complying with [Federal] Rule [of Civil Procedure] 11(b)(3), that is precisely the result the First Amendment requires.

Read the judge’s full decision below (remember, it gets really good after page 23):

Nunes v Hearst, Lizza Opinion and Order by Law&Crime on Scribd

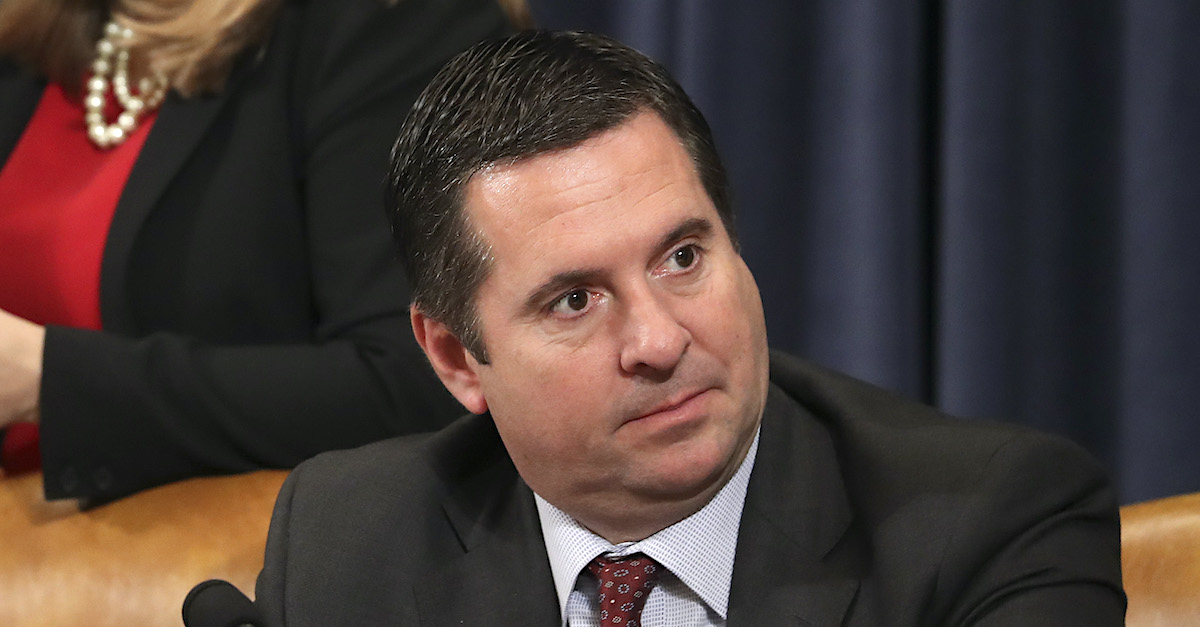

[photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images]