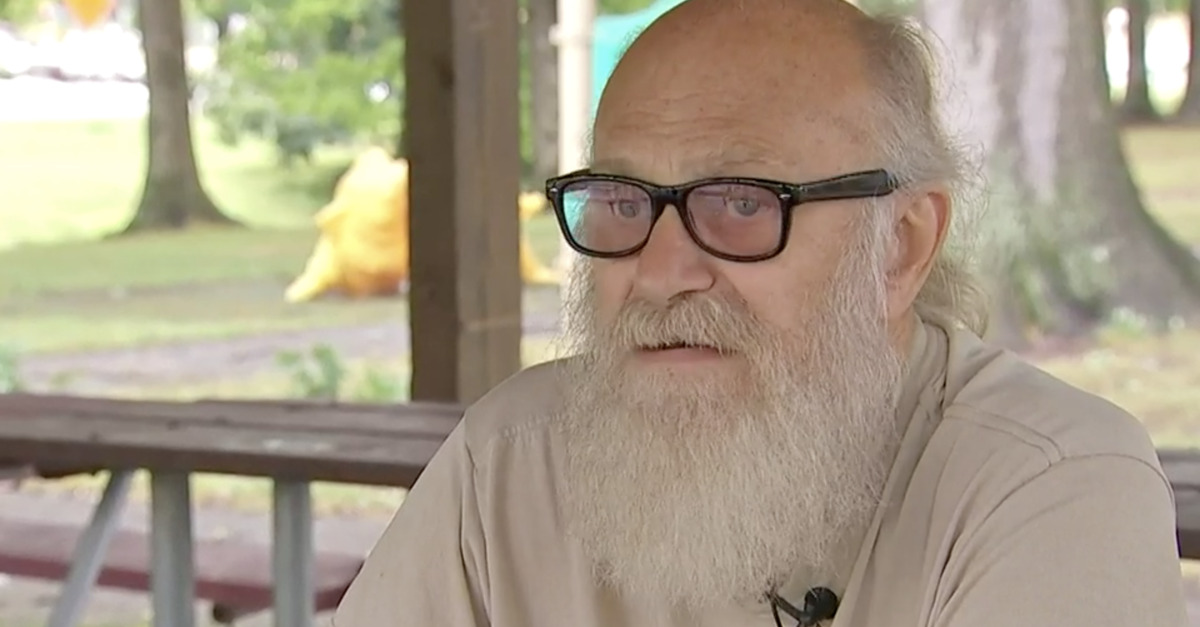

Before DNA evidence exonerated him of the crime, Lewis Fogle was convicted of raping and murdering a teenage girl and spent 34 years in prison. The world changed around him. His son grew up without a father. Now, he says he wants the police, attorneys and the county that got him wrongly convicted and imprisoned–despite the lack of any physical evidence–to pay.

“They’ll falsify evidence, witnesses, change the events of the crime, even pay witnesses to lie just to rest a conviction,” Fogle recently told Pittsburgh-based NBC affiliate WPXI, as his federal lawsuit nears its fifth year. “I think the criminal justice system is broken and it needs to be redone.”

Freed in 2015 by DNA evidence after a joint motion filed by the Innocence Project and then-Indiana County district attorney Patrick Dougherty, Fogle initially faced the prospect of a retrial but prosecutors declined to retry their hand citing a lack of evidence.

Fogle claimed Keystone State authorities relied on the word of someone known as “Spaceman,” amateur hypnosis and jailhouse informants to bring him up on charges over the 1976 rape and murder of Deann Katherine “Kathy” Long–some six years after the 15-year-old’s brutal fate had originally befuddled investigators.

Firing back against seven men who worked as Pennsylvania State Troopers during the investigation, Fogle sued them for federal civil rights violations in a 2017 lawsuit. Also named as defendants in the lawsuit are the county itself as well as the former district attorney and assistant district attorney who brought the decidedly bizarre case to trial.

Some three years into the case, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals rejected most, but not all, law enforcement claims of immunity in a unanimous opinion which ended on a mournful note.

“Our decision offers little to celebrate,” U.S. Circuit Judge Paul Matey wrote in 2020, giving the green light to Fogle’s lawsuit. “Lewis Fogle can move forward with some, but not all, of the allegations in his complaint against the prosecutors. The prosecutors must explain some, but not all, of their choices. And decades later, answers and earthly peace still elude Deann ‘Kathy’ Long and her grieving family.”

Long was raped and then shot once in the back of head in the woods of Western Pennsylvania. Her body was discovered near her home by a passerby who was out picking blackberries in late July. The one thing state troopers knew was “that Kathy was last seen getting into a blue car with an unknown man,” according to her sisters and family friends.

The man was described by Long’s two younger sisters, also both minors, as “as between 20 and 30 years old, with blue eyes, black hair that came below his ears and curled at the ends, sideburns, heavy eyebrows, and a heavy mustache over his upper lip.”

Fogle says he did not match the description and was contemporaneously described as having “straight reddish-blonde hair that dropped down his back and a matching, full beard that reached his waist.”

According to the initial timeline, Kathy Long got into the car with the black-haired man on the evening of the day she was killed–a timeline originally corroborated by her older sister, Patty Long, and a friend of the family. Eventually, police and the prosecution would blow up this timeline and render it irrelevant in their efforts to put Fogle behind bars, he claims.

A year passed. According to the lawsuit, police turned to Earl Elderkin, a man known colloquially throughout Indiana County as “Spaceman,” because “he claimed that he and his kids were from outer space.” Fogle says Elderkin fit the description of the black-haired man in the blue car but initially denied having any knowledge of, or connection to, the crime.

His story changed several times after that, Fogle says. And, with each concomitant twist, distortion and possible culprit, authorities admitted to themselves that Elderkin had no credibility whatsoever; the fact of his extreme drug and alcohol use fueled investigators’ reticence to accept any of his numerous narratives about the crime, according to the lawsuit.

Fogle claims that after three more years and with no form of progress or credible leads, state troopers returned to Elderkin–who had, by this time, allegedly checked himself in to a mental health facility.

The Third Circuit summarizes Fogle’s account of Elderkin’s shifting stories in February 1981:

In one of these versions, he implicated sixteen unidentified men; in the other, he named two specific individuals, but neither was Lewis Fogle. And these new contradictory statements only diminished Elderkin’s credibility. His stories included variations on the number of people involved in the murder and consistently referenced passengers in the blue car, a detail Kathy’s sisters never mentioned. Even Elderkin agreed he was unreliable, stating he was not sure whether he had witnessed a murder, or merely imagined the whole thing.

Undeterred, Fogle claims, state troopers and then-district attorney Gregory Olson turned to what the National Registry of Exonerations termed “a college professor who was an amateur hypnotist with no formal training.”

Judge Matey also described the session:

Unusual too was the actual hypnosis session, with the “hypnotist” acting “[a]t the behest of Defendants” to use “undue suggestion to obtain a statement from Elderkin.” But even that direction proved insufficient, as Elderkin waffled between versions of his earlier statements and a new story implicating, for the first time, both Dennis and Lewis Fogle. Following the hypnosis sessions, Olson and the State Troopers again interviewed Elderkin. And this time, he at last provided a firm statement naming the Fogle brothers as two of four attackers. That statement became the cornerstone of the investigation.

Fogle claims that Elderkin’s hypnosis theory did not align with that first piece of information that police had relied on: the timeline provided by Kathy’s sisters and friends. But authorities persisted, he says.

“To advance their case, the State Troopers brought in Kathy’s older sister, Patty, and one of Patty’s friends, for a long interview,” Matey wrote in his April 2020 opinion, summarizing Fogle’s allegations. “Eventually, under intimidation and threats of arrest by the State Troopers, they altered their story to align with Elderkin’s latest story. At least for a time, as Patty’s friend recanted her statement soon after leaving the station.”

Then, “following hours of interrogation, threats, and a steady stream of suggestion,” Dennis Fogle implicated himself, his brother Lewis and two others in the rape and murder–pinning the rifle blast to the back of Long’s skull on his brother, according to the opinion’s synopsis of the lawsuit. Fogle says that this confession curiously matched almost word-for-word with what Elderkin was attributed with telling the English professor during the non-recorded hypnosis session.

Soon enough, the accused Fogle–who had a consistent alibi vouched for by two witnesses–says he learned where the police got their information and so did the court. The Elderkin session was ruled inadmissible–the “Spaceman” himself was barred from testifying. Dennis Fogle’s coerced confession was suppressed.

Their case all-but dead in the water, Lewis Fogle claims, police and the prosecution then conspired to maintain their false claims against him through the use of jailhouse informants.

Judge Matey breaks down Fogle’s claims this way:

Timely support soon arrived from jailhouse informants recruited and counseled by the State Troopers. Working collaboratively with law enforcement, and pursuing promises of leniency, two of Lewis Fogle’s cellmates claimed Fogle confessed to Kathy’s murder. Olson and [then-assistant district attorney William] Martin “either knew about, encouraged, or permitted” this strategy. While the State Troopers characterized these statements as voluntary, they and the Prosecutors “hid” their role in pursuing the witnesses and their offers of favorable treatment.

Six years after the Long’s murder, Lewis Fogle was convicted. At the time, the innocent man was a newlywed. His son was 7 months old.

Decades later, Fogle is out of prison but says he doesn’t feel free.

“I had what I wanted in life and in a snap of the fingers, it was all gone,” he told WPXI last week. “A lot of them I tried writing to and just never heard back from them. The law said I did it so I had to have done it.”

“Most of the time I just feel like I’m back in prison. Life is not my own,” Fogle continued. “I try to get a job, try to find housing and I’m turned down every time. Even my right of being a father were taken from me.”

A status conference in his civil rights lawsuit against Olson, Williams, Indiana County and then-state troopers John Sokol, Michael Stefee, Donald Bechwith, Joseph Stephen, John Bardroff, Andrew Mollura, and Glenn Walp is currently slated for Aug. 25.

[image via screengrab/WPXI]