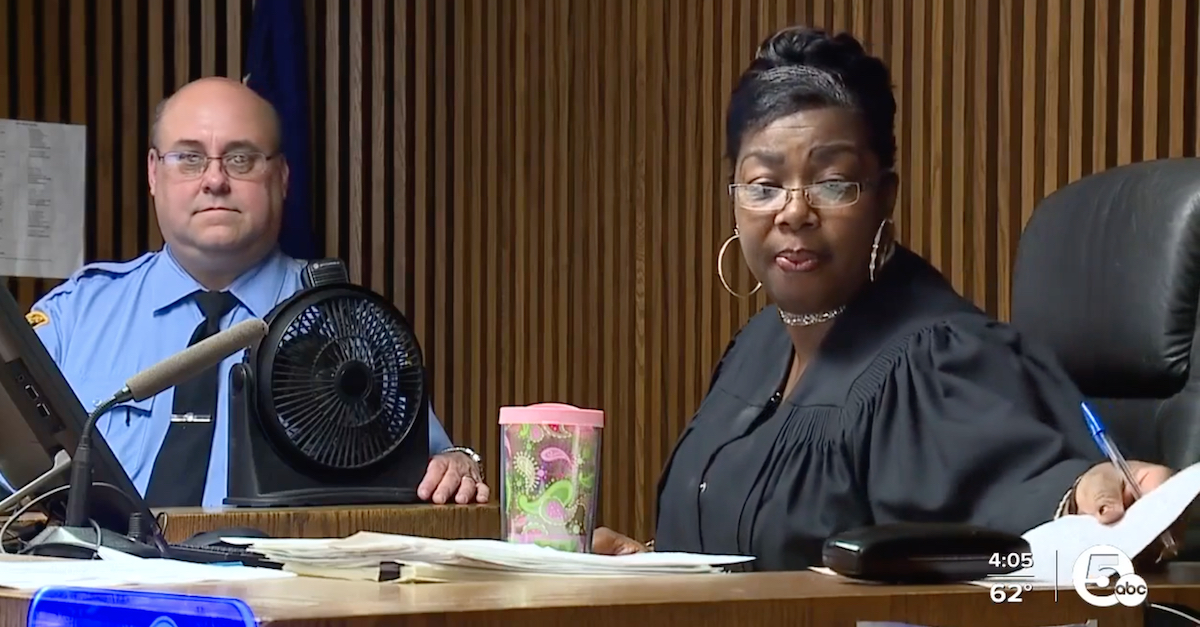

Pinkey Suzanne Carr holds up a sign in court. The context of the sign was not immediately clear from a local television report. (Image via WEWS-TV screengrab.)

The Ohio Supreme Court this week “indefinitely” and “immediately” suspended a Cleveland municipal judge who disciplinary authorities said had “conducted business” like a “game show host.” The judge’s conduct included offering bizarre deals to defendants when prosecutors were not present on dates that coincided with her birthday, their birthdays, the birthdays of friends, or holidays.

Pinkey Suzanne Carr had been a Cleveland Municipal Court judge since January 2012, according to the high state court’s unsigned per curiam opinion. Prior to that, she was an assistant Cuyahoga County prosecutor.

“On multiple occasions, Carr joked that she would be amenable to some form of bribe in return for a lenient sentence,” the state supreme court said in a lengthy suspension order. “In open court, she engaged in dialogues with defendants about accepting kickbacks on fines and arranging ‘hook-ups’ for herself and her staff for food and beverages, flooring, and storage facilities.”

Discipline Panel Suggests Punishment

In March 2021, disciplinary authorities accused Carr of five counts of misconduct involving “more than 100 stipulated incidents” spanning a two-year time frame, the state supreme court’s opinion indicates. They broadly involved these categories:

(1) issuing capias warrants and making false statements,

(2) engaging in ex parte communications and improper plea bargaining and rendering arbitrary dispositions,

(3) using capias warrants and bonds to improperly compel payment of fines and court costs,

(4) exhibiting a lack of decorum and dignity in a judicial office, and

(5) abusing contempt power and failing to recuse herself from contempt proceedings in which she had a conflict.

Those accusations are much more verbose than that short list suggests.

“The parties entered into 583 stipulations of fact and misconduct that span 126 pages and submitted more than 350 stipulated exhibits,” the opinion states.

A professional conduct panel determined that Carr “ruled her courtroom in a reckless and cavalier manner, unconstrained by the law or the court’s rules, without any measure of probity or even common courtesy,” the opinion goes on.

The panel also determined that she “conducted business in a manner befitting a game show host rather than a judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court.”

Accordingly, the panel found that the judge’s actions “could not help but seriously compromise the integrity of the court in the eyes of the public and all who had business there.”

The panel recommended a two-year suspension from the practice of law and “certain conditions” on her reinstatement, the court noted.

Carr, however, said that the “board applied the wrong legal standard” to her case “and failed to accord proper mitigating effect to her mental-health disorders,” the court recalled.

Carr further disputed the board’s suggested punishment: she said 18 months of the contemplated two-year suspension should be “conditionally stayed” (or set aside).

Ohio Supreme Court Issues Suspension

The Ohio Supreme Court rubbished Carr’s suggestions and held that the discipline board’s suggestion was far too lenient.

“We adopt the board’s findings of misconduct,” the high court said — thus adopting the factual material that predicated the punishment.

“For the reasons that follow, we overrule Carr’s objections, reject the two-year suspension recommended by the board, indefinitely suspend Carr from the practice of law, and immediately suspend her from judicial office without pay for the duration of her disciplinary suspension,” the Ohio Supreme Court ordered.

Pinkey Suzanne Carr.

Covid-19 Orders Flaunted

Specifically, in March 2020, Judge Michelle Earley, the judge in charge of the municipal court system, suspended courthouse activity because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite Earley’s order, Carr “did not reschedule cases set on her docket,” the supreme court found.

Rather, despite the courthouse being basically closed, Carr “issued capias warrants for the defendants who did not appear in court.”

Those warrants ordered arrests and set bonds between $2,500 and $10,000, the high court noted.

“In contrast,” the high court continued, “Carr waived fines and court costs for defendants who were ‘brave enough’ to appear in court despite the potential for exposure to COVID-19.”

When a public defender began to question the fundamental fairness of ordering defendants to appear when the courthouse was listed as officially closed, Carr told the public defender that “not everyone watches the news” and that defendants should, indeed, appear in spite of Earley’s Covid-19 order. When the public defender left the courtroom, Carr “turned to her staff and mocked him, calling him a ‘little idiot,'” the Ohio Supreme Court said.

Later, Carr learned that Matthew Woyma, the person responsible for scheduling court cases, had cleared several civil matters from the docket because of Earley’s order. Carr, in “open court,” told her bailiff to tell Woyma “to get his ass back on that phone and put all [her] civil cases back on,” the supreme court indicated.

Carr’s actions attracted the attention of the regional newspaper, the Cleveland Plain Dealer, yet she continued, the high court went on to note. A newspaper article cited in the supreme court’s opinion said Carr kept her courtroom open despite a red banner appearing atop the municipal court’s website indicating that court was closed — a move that was confusing at best.

According to the newspaper’s report, Carr refused to comment, but she did, according to the Ohio Supreme Court, grant an interview to a local televisions station. Therein, according to the high court, she called the newspaper report “untrue” and “reckless.”

“And you are not, to be clear, you are not issuing any warrants?” a television reporter asked, according to the supreme court’s retelling of the interview broadcast by an unnamed TV station.

“Absolutely not,” Carr replied.

“However, that statement was untrue,” the supreme court immediately commented in hindsight.

In other words, according to the opinion, Carr lied to the television station.

Carr then dug in further and “continued to falsely characterize her actions” in text messages to Earley, the supreme court said.

The public defender’s office eventually filed a complaint to address the matter.

Pinkey Suzanne Carr.

Those woes weren’t the end of Carr’s troubles. To wit, Carr had an apparent track record of offering plea deals to defendants without prosecutors present.

Deals Without Prosecutors Present

“The parties’ stipulations describe 34 cases in which Carr engaged in ex parte communications and improper plea bargaining with defendants and made arbitrary rulings between May 2019 and December 2020,” the state supreme court’s order indicates.

The high state court outlined the issues with that practice:

Carr admitted that she routinely conducted hearings without a prosecutor being present so that she could avoid complying with the requisite procedural safeguards set forth in R.C. 2937.02 et seq. (requiring a judge to inform the accused, among other things, of the nature of the charge, the identity of the complainant, the right to counsel, and the effect of a plea of guilty, not guilty, or no contest) and Crim.R. 11 and Traf.R. 10 (both requiring a judge to engage in a personal colloquy with the accused to ensure that a plea is knowingly and voluntarily entered). Carr also unilaterally recommended pleas to unrepresented defendants when no prosecutor was present and accepted the pleas without explanation or discussion of the consequences of entering the plea, as required by Crim.R. 11 and Traf.R. 10. In at least 6 of the 34 cases identified in this count, Carr unilaterally amended the charges against the defendant and falsely attributed those amendments to the prosecutor in her judgment entries.

After unilaterally entering no-contest pleas on behalf of defendants, Carr routinely found them not guilty of the charged offenses. But even when she found defendants guilty, she arbitrarily waived fines and costs without any inquiry into the defendant’s ability to pay. She then falsified her journal entries to conceal her actions. In fact, Carr frequently stated that she was waiving fines and costs based on the defendant’s birth date or its proximity to the date of the hearing, a holiday, her own birthday, or the birth dates of her family and friends—even when the prosecutor was present in her courtroom. Carr’s entries in at least 24 of the 34 cases identified in Count Two falsely stated that she had conducted ability-to-pay hearings and had determined that the defendants were unable to pay fines or costs.

“Modern-Day Debtors’ Prison”

In another area of concern, the state supreme court said Carr “admitted” at her disciplinary hearing that she used capias warrants and jail time to “essentially create[] a modern-day debtors’ prison.”

Her response to complaints about her method resulted in what the disciplinary board said was a “characteristically colorful explanation” for halting her practices:

You notice I’m no longer the bill collector for the Clerk’s Office. I’m not your b-i-t-c-h. See, you get it? Collect your own money. There you go, player, mm-hmm. Collect your own money, player, mm-hmm. I’m not your b-i-t-c-h. Run tell that, mm-hmm. Mm- hmm. How you like them apples? Suckas.

“Dolls, Cups, Novelty Items, and Junk”

And then there was a generalized “lack of decorum and dignity,” the supreme court found:

In addition to violating statutes, rules, and court orders designed to protect the legal interests of the public and the litigants in courtrooms throughout this state, Carr presided over her courtroom from a bench covered with an array of dolls, cups, novelty items, and junk that her own counsel found to resemble a flea market. Carr testified that her bench had been that way since 2012, but that she had cleared it off a few months before her disciplinary hearing. She also violated rules governing appropriate courtroom dress, order, and decorum. From the appearance of her bench to the way she dressed and the way she treated the attorneys, litigants, and staff in her courtroom, Carr undermined public confidence in the independence, integrity, and impartiality of the judiciary.

Her attire also raised concerns, according to the supreme court’s opinion:

Despite the dress and decorum expectations for the general public, Carr presided over her courtroom wearing workout attire, including tank tops, t- shirts (some bearing images or slogans), above-the-knee spandex shorts, and sneakers.

Carr was aware that the public took notice of her unconventional appearance. She once told a defendant’s counsel, “Your client was scared to come in. Officer Gray said he asked her, ‘Well, where is the Judge?’ She was like, ‘She in there,’ and he was like, ‘The one in the T-shirt?’ He said, ‘I’m calling my lawyer.’ He said, ‘Un-uh. This couldn’t be real.'” She then explained to counsel, “I dressed up Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday. It’s not happening today, and tomorrow is a national holiday, Juneteenth. I’m not doing it, okay?”

The board found that Carr reveled in her lack of decorum, telling one defendant who apologized for his own attire, “You see how I’m dressed? I have on my Cavs’ T-shirt.” After another defendant expressed surprise that he had been found not guilty, Carr responded, “You can trust me. I know I’m not dressed like a judge, but I’m really the judge.”

“Set in a Mississippi Strip Club”

There was more.

“During a series of proceedings in open court, Carr maintained a dialogue with her staff and defendants about the television series P-Valley, which is set in a Mississippi strip club,” the state supreme court quipped.

Carr also allegedly referred to one of her bailiffs, Alicia Gray, by the name of a character from that series called “Ms. Puddin.”

The high court indicated that Carr’s cavalier attitude appeared to be one-sided at times:

Although Carr frequently behaved as though the rules of courtroom decorum did not apply to her, she did not hesitate to correct defendants for seemingly minor infractions. The video evidence shows that she repeatedly admonished defendants for standing with their hands crossed or in their pockets instead of at their sides and screamed at them when they indicated that they had not heard what she said. Carr also resented being called “ma’am” and berated defendants who attempted to show their respect for her by using that honorific. When male defendants referred to her as “ma’am,” Carr would chastise them, calling them “little boy.”

“I Got Us Another Hookup”

Using a defendant’s initials, here’s how the high court said the aforementioned “hook-ups” played out in court:

E.W. appeared before Carr on July 22, 2020, to request that she grant him driving privileges in his 2018 case for driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol. After being informed that E.W. worked for an automotive company, Carr told her staff, “I got us another hookup. We could get our cars fixed here,” and she stated that she had already gotten them some flooring and carpet. E.W. told her to bring their cars in and that the company would love to take care of them. Carr replied, “Always getting us the hookups. Don’t worry, we don’t have to pay. It’s on him.”

Reinstatement of E.W.’s driving privileges was subject to a mandatory $50 fee. But when E.W. indicated to Carr that he did not have the money to pay the fee, Carr said, “Well who’s going to pay his $50. Puddin gets paid today, so does Mike. They both got $50, after all, you hooking us up. Maybe they will pay your $50. $50 fee waived. All right. You’re all set.” On the journal entry, Carr wrote “No Bitching Necessary.” She then passed the journal entry to a bailiff and told him, “Show that [judgment entry] to Ms. Puddin.” As Gray read the entry, Carr broke out laughing while her bailiff called the next case.

“How Does Sleep Apnea and Menopause Contribute to Lying?”

Carr, as noted above, raised mental disorders as an explanation for her conduct. However, the state supreme court concluded that her cited disorders — generalized anxiety and a mood disorder connected sleep apnea, stress, and menopause — were not the cause of what occurred.

“How does sleep apnea and menopause contribute to lying?” one justice asked during oral arguments about the case, according to coverage by Cleveland ABC affiliate WEWS.

Carr’s attorney said those issues affected her “mood” and “ability to think clearly.”

The court disagreed.

“An Indefinite Suspension”

The state supreme court concluded on the following punishment:

Carr’s unprecedented misconduct involved more than 100 stipulated incidents that occurred over a period of approximately two years and encompassed repeated acts of dishonesty; the blatant and systematic disregard of due process, the law, court orders, and local rules; the disrespectful treatment of court staff and litigants; and the abuse of capias warrants and the court’s contempt power. That misconduct warrants an indefinite suspension from the practice of law.

Indefinite suspensions are not necessarily permanent. Carr can reapply for her law license but must submit reports from healthcare professionals and assurances of compliance with a contract she signed with the Ohio Lawyers Assistance Program, the opinion states. Additionally, she must wait at least two years before seeking readmission, according to the supreme court.

A partial dissent says Carr’s road ahead will be difficult if the now-former judge chooses to rejoin the legal profession.

The two judges who partially dissented said indefinite suspensions are usually reserved in the Buckeye State for judicial conduct that is also criminal: embezzling funds, lying to the FBI, felonious assault, domestic violence, sexual harassment, and campaign finance offenses are among the issues that have led to indefinite suspensions in other Ohio cases cited by the dissent.

The dissenting jurists said a two-year suspension would have been sufficient because it would have removed Carr from judicial office while also making it easier for her to someday represent private clients.

The 37-page discipline order is available here in its entirety.