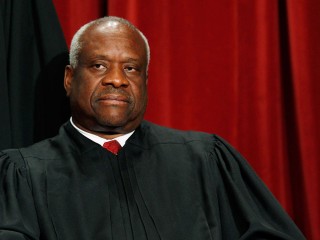

Clarence Thomas just penned the latest installment in his growing list of appalling opinions. And without Scalia around to share the title of Most Misguided Jurist, Thomas is now alone on his discrimination-blind island.

Clarence Thomas just penned the latest installment in his growing list of appalling opinions. And without Scalia around to share the title of Most Misguided Jurist, Thomas is now alone on his discrimination-blind island.

Monday, the Supreme Court ruled 7 to 1 that Timothy Tyrone Foster, a death-row inmate, received an unfair trial in 1986 when Georgia prosecutors blatantly violated rules about racial discrimination during jury selection. Foster, a black man, was convicted of killing a white woman by an all-white jury, after the prosecution purposely kept all blacks off the jury. This SCOTUS decision wasn’t exactly a nail-biter. This wasn’t a case where there was a suspicion of discrimination; this was one where there was clear, unequivocal evidence that the prosecution was executing a complete and systematic commitment to excluding black jurors. Following Batson v. Kentucky, a 1986 SCOTUS case that preceded the Foster trial, the illegal dismissal of jurors solely on the basis of race became known as a “Batson violation;” As Justice Elena Kagan pointed out, the clear, handwritten notes that blacks be dismissed from the Foster jury is “about as clear a Batson violation as a court is ever going to see.”

For anyone familiar with the O.J. Simpson trial, the idea of preferring jurors because of their race isn’t all that shocking. Jury selection is certainly supposed to be color- blind, but like many things, often isn’t. Racism seeps its way into our courtrooms, tainting our justice in subtle ways; but overt discrimination by the prosecution is something unusual. In Foster’s case, there was no pretext – no reason other than race for challenging the selection of the black jurors. Given that Batson was new law at the time of Foster’s trial, it’s not surprising that some prosecutors were comfortable keeping records of practices that had long been used, but that had only recently been deemed illegal. Regardless of the close timeline, though, the trial of Timothy Tyrone Foster was corrupted by the prosecutors’ illegal manipulation of the jury.

The overwhelming evidence of the prosecution’s discriminatory intent makes the SCOTUS majority decision quite fair, but not all that important. It’s unlikely that we’ll see many other cases in which the prosecution kept detailed records about its blatant racism, so I wouldn’t expect thousands of convictions to suddenly be overturned on the basis of this precedent.

Thomas’ dissent, on the other hand, is important – for it is a window into a kind of thinking that is dangerous in its obtuseness. Thomas’ argument that SCOTUS lacks jurisdiction over Foster’s appeal has a distinctly protesting-too-much vibe to it. Thomas prattles on about res judicata for a few tiresome pages that few will read and with which even fewer will agree, before he cloaks his unwillingness to acknowledge racial bias in an absurd level of deference to the trial court. If I can paraphrase, Thomas’ reasons for dissenting were: 1) this isn’t my problem; 2) I don’t want to get involved; and 3) I don’t see anything wrong here.

Clarence, you’re on the damn Supreme Court. Your entire job is to second-guess the work of other judges. While we’re at it, how about paying attention to discrimination that landed someone on death row?

What Thomas should be doing is taking up the gauntlet set down by Thurgood Marshall, the namesake of Thomas’ SCOTUS seat. He should be finding errors of justice and doing his part to correct them. But Thomas’ refusal to do so in a case involving racial bias isn’t surprising from someone who has declared that slavery actually “did not strip slaves of their dignity.”

I realize that as a Yale-educated, successful, presidential appointee who circumvented a nationally-publicized sexual harassment scandal, Clarence Thomas isn’t exactly the poster child for “The Black Experience in America.” But come on. He might not, personally have been a recipient of the a-little-less-fair, a-little-more-harsh brand of justice usually reserved for racial minorities. But he has to know that such discrimination and marginalization exists – particularly in Georgia, where Foster was convicted, and, coincidentally, where Thomas grew up.

In his dissent, Thomas’ signature willful blindness reached new levels when he suggested that the abundant evidence that the prosecution had purposely excluded black jurors just wasn’t there. Thomas was moved neither by a handwritten notation on the jury list reading, “NO. No Black Church,” nor by a list of otherwise-qualified black jurors labeled, “definite NO’s” [sic], nor even by the prosecutor’s statement that, “[i]f it comes down to having to pick one of the black jurors, [this one] might be okay.”

That seven other Supreme Court justices did see the obvious plan to maintain an all-white jury apparently left Thomas unconcerned. In his dissent, he excuses the prosecutors’ behavior as internal office debate, or irrelevant personal opinion. Thomas, for all his staunch revere of discipline and conservatism, seems awfully willing to overlook misconduct that resulted in a death sentence.

But the part that is truly frightening is Thomas’ assertion that with Monday’s decision, the Court has set dangerous precedent that will allow prisoners to demand review of prosecution files in their cases. Isn’t that kind of the point? Don’t we want government to be accountable for its work, particularly when that work lands people on death row? I’m all for judicial efficiency, but if people are getting convicted of murder after the prosecution is breaking the law, I think it’s worth the trouble to have a quick look through the files.

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.