During an email exchange with right-leaning commentator Ben Shapiro, liberal journalist Kurt Eichenwald made several scurrilous comments about pro-gun Parkland teen Kyle Kashuv.

As a result of this email, Kashuv likely has a valid defamation case against Eichenwald if he decides to take legal action. Specifically, he could sue for defamation by libel. At issue would be various statements Eichenwald made about Kashuv’s alleged mental deficiencies.

At 7:56 a.m. on Tuesday, Eichenwald wrote:

I consulted a friend of mine who is a psychiatrist – a political conservative, since that seems so important to you – and based on what he read, the psychiatrist said the following:

1. Kyle is in desperate need of psychiatric help or support. The psychiatrist did not have enough information to assess if the issues he saw in the conversation were the consequences of the shooting, being unprepared for being thrust into the conservative media as a go-to kid, or if there is an underlying pathology that preceded these events.

2. Kyle is obsessed with you. In fact, our DM conversation, which involved a lot of irrational rage, seemed to have been sparked by my asking you to debate. (That invitation still stands.) Kyle demanded that I stop asking you to debate in the midst of a diatribe that the psychiatrist found deeply disturbing.

Kyle Kashuv lives in Florida, so Florida would be the most likely jurisdiction. Under Florida law, the elements of a defamation claim are: (1) the defendant published a false statement; (2) about the plaintiff; (3) to a third party; and (4) the falsity of the statement caused injury to the plaintiff. This restatement of Florida’s defamation test comes by way of fairly recent precedent from the case Border Collie Rescue v. Ryan. Let’s take each element in turn.

1. Eichenwald Likely Published A False Statement

Here, Kashuv could plausibly argue Eichenwald has more or less accused Kashuv of being mentally ill. Kashuv has suggested that he doesn’t have a mental illness diagnosis and this is likely true. The following statement isn’t an explicit affirmation of Kashuv’s purported mental illness but it’s likely enough to qualify as false and defamatory: “Kyle is in desperate need of psychiatric help or support.”

Eichenwald then digs himself into a deeper hole by suggesting that Kashuv might have “an underlying pathology,” which is deeply irresponsible and not likely to be viewed favorably by either a judge or a jury. Eichenwald additionally piles on to his own potential legal problems by referring to Kashuv’s alleged obsession with Shapiro and asserting that this so-called obsession led to “a diatribe that the psychiatrist found deeply disturbing.”

The fact that Eichenwald used a conservative psychiatrist to launder criticism of Kashuv is immaterial. Long-established law holds that republication of defamatory statements itself incurs liability. The psychiatrist made the statement and could be liable for making it as well. Eichenwald would likely be liable for republishing the psychiatrist’s statement.

(Editor’s note: Shapiro’s republication of the statement would likely subject him to liability here as well, but this is almost certainly a moot point because Kashuv isn’t likely to file a lawsuit against Shapiro–who is his ideological comrade and apparent friend. The statute of limitations for defamation in Florida is two years, though, so if anything changes for Kashuv politically during that time period, Shapiro could very well find himself on the losing end of a lawsuit.)

2. The False Statement Was About Kashuv

This element is obviously and easily satisfied because Eichenwald repeatedly refers to Kyle Kashuv throughout the email to Shapiro. At the beginning of the email, Eichenwald references an article he’s writing about Shapiro and Kashuv where he doesn’t plan to use Kashuv’s name. That’s fine and dandy. Eichenwald’s forthcoming article–the one said to be excising Kashuv’s name–wouldn’t form the basis of a defamation lawsuit. The email itself is the basis.

3. Eichenwald Published The False Statement To A Third Party

Again, this is element is easily satisfied though perhaps it’s not so obvious. Most people would not consider their personal (or work-related) emails to count as publications. But the law does and this is highly settled jurisprudence. Publication to a third party means any form of publication and any third party would qualify. Or, in other words, any communication made to a third party who understands the communication would qualify as a publication. Here, Shapiro is the third party who counts. By sending the likely defamatory statements to Shapiro via email, Eichenwald published them.

4. The Falsity Of Eichenwald’s Statement Is Presumed to Have Caused Kashuv Injury

Under Florida law, in a traditional defamation case, a plaintiff would have to allege actual damages. This is where many defamation scenarios run off the rails because actual damages can be difficult to quantify under such circumstances. (Whether Kashuv could prove–or would plead–actual damages is an open question but is not being addressed here because it’s simply too fact-specific and those facts are not available as of now.) Luckily for Kashuv, Florida is a defamation per se jurisdiction.

Defamation per se is a legal doctrine which holds that certain statements are so inherently damaging they create an assumption that damages exist simply because the statement was communicated in the first place. The longstanding concept of per se defamatory statements includes comments that suggest or assert a person has a “loathsome disease.” This is a fairly ancient–and therefore socially problematic–legal term of art. Without endorsing the ableist idea that mental illness is “loathsome,” suffice it to say that courts have interpreted statements accusing plaintiffs of suffering from mental illness to fall into this category.

Furthermore, the prospect of filing a defamation per se action against Eichenwald could possibly render one of his potential defenses inoperative. Many defendants win defamation cases against them because the person they’re accused of defaming is some sort of public figure. Kashuv is a media personality and clearly engages with his critics publicly, therefore Kashuv probably qualifies as a public figure. Therefore, the standard Kashuv would likely have to prove is “actual malice.”

According to the Supreme Court, “actual malice” means that a statement was communicated with knowledge of its falsity and/or reckless disregard for the truth. It would probably be exceedingly difficult to prove Eichenwald had knowledge of falsity because he purports to believe what he said about Kashuv is true. But many have suggested the conservative psychiatrist is possibly fictional. We’re agnostic on this point. In any event, Kashuv could very well argue Eichenwald acted with reckless disregard for the truth here.

Law&Crime reached out to Eichenwald for comment on this story generally and specifically regarding his potential libel liability. His on-the-record comments are provided here in full:

“I sent Ben an email regarding a magazine article about Ben that was in its very early stages. I had already conducted other reporting before reaching out to Ben. As with most reporting, that entailed asking questions and laying out the context for those questions. This doesn’t mean I had a magazine article I was publishing–this means I was exploring. I’m suddenly being held accountable for an email as if it was the article.

“I explained the concern I had for this boy’s well-being. I explained why I had this concern. The purpose of saying so was to say to Ben ‘You might be causing damage–don’t forward this email. And I did not make a declaration, I said, I consulted an expert and the expert says: ‘This kid could be traumatized. This kid could be overwhelmed by the situation he’s in. Or there could be a pre-existing pathology.’ That’s what was said. The point of it was not to say, ‘Kyle is crazy.’ The point is to say that there could be a problem here.

“If I couldn’t have done this story without potentially harming Kyle, I would not have done it. It never occurred to me that a professional would be this reckless and care this little about the well-being of a child who has undergone a traumatic experience. Who has been put in a position that few teenagers would be able to emotionally manage and throw him back into this. So, the entire point of my saying this–it wasn’t my opinion; it was—was to say: be careful. Don’t send this to the kid. There’s something wrong–maybe it’s just trauma, who knows? But an expert thinks there’s something wrong and let’s not do this while I’m exploring this story.”

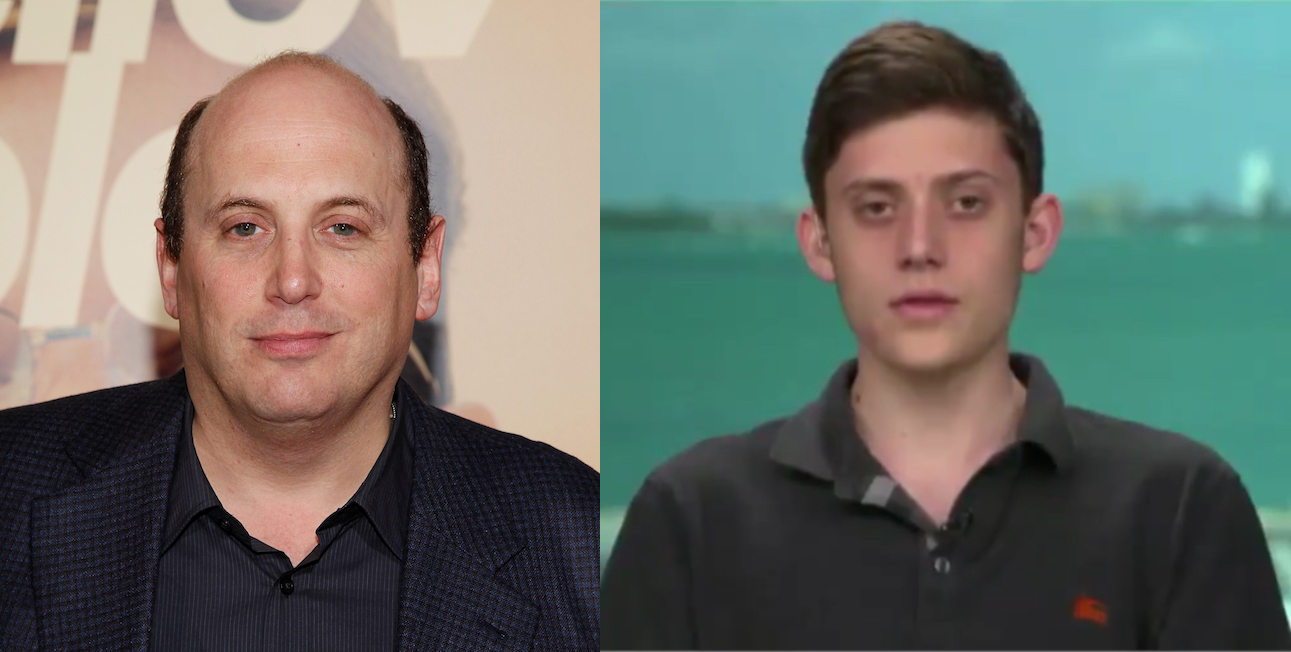

[image via Charles Eshelman/Getty Images/screengrab/Fox News]

Follow Colin Kalmbacher on Twitter: @colinkalmbacher

Editor’s note: as helpfully noted by Ken White and Marc Randazza, defamation per se does not defeat the necessity to find actual malice. Under Florida law, a finding of per se defamation assumes malicious intent, however, the original phrasing was confusing and off-base. As a result, this article has been amended since publication.