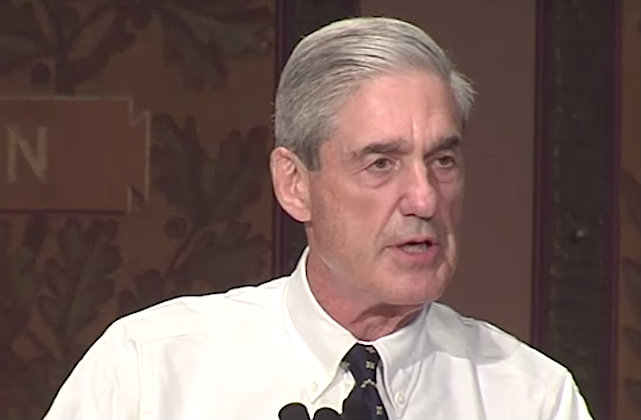

The law is clear: Special Counsel Robert Mueller must recuse from any Comey-part of his special counsel inquiry. As the Department of Justice itself promises the world, “No DOJ employee may participate in a criminal investigation or prosecution if he has a personal or political relationship with any person or organization substantially involved in the conduct that is the subject of the investigation or prosecution, or who would be directly affected by the outcome.” A personal relationship “means a close and substantial connection of the type normally viewed as likely to induce partiality.” This requirement derives directly from section 45.2 of the Code of Federal Regulations. The law reads the requirement of recusal as mandatory: Mueller “shall” recuse from the Comey part of the inquiry if Mueller has a “personal relationship” with Comey.

The law is clear: Special Counsel Robert Mueller must recuse from any Comey-part of his special counsel inquiry. As the Department of Justice itself promises the world, “No DOJ employee may participate in a criminal investigation or prosecution if he has a personal or political relationship with any person or organization substantially involved in the conduct that is the subject of the investigation or prosecution, or who would be directly affected by the outcome.” A personal relationship “means a close and substantial connection of the type normally viewed as likely to induce partiality.” This requirement derives directly from section 45.2 of the Code of Federal Regulations. The law reads the requirement of recusal as mandatory: Mueller “shall” recuse from the Comey part of the inquiry if Mueller has a “personal relationship” with Comey.

This is where the ethical concern arises: a partial prosecutor will favor one party over another due to their personal relationship with one of those parties. To assess the Comey-connected issues requires review of Comey’s behavior, assessment of Comey’s intent, and judgment of Comey’s credibility. According to published media reports and near unanimity of those who know both, Mueller enjoys an “unusual friendship” with Comey in their closeness. Their actions as public servants particularly “deepening a friendship forged in the highest levels of the national security apparatus.” To many Trump supporters, that sounds like a Deep State alliance forged in the fires of another more unearthly place. The public articles read more like a modern bromance, that “stretches back over a decade” of closeness and simpatico sentiments toward and for one another’s “shared” perspectives.

Five separate sets of standards govern the conduct of special counsel for the Department of Justice. First, the conflict of interest laws imposed by Congress in sections 201 through 209 of Title 18 of the United States Code. Second, the executive orders of the White House, including Executive Order 12674, 12731, and 13490, all amended and updated by President Barack Obama. Third, the integrity restrictions of section 423 of Title 41 of the United States Code governing procurement policy. Fourth, the standards of conduct governing appointed officials under section 2635 of Title 5 of the Code of Federal Regulations. Fifth, and finally, the Department of Justice’s standards of conduct for Department appointees under section 3801 of Title 5 of the Code of Federal Regulations and section 45 of Title 28 of the Code of Federal Regulations. Mueller, as an attorney licensed in California (and, apparently, elsewhere), the ethical standards governing California counsel also govern Mueller’s conduct.

At the outset, it is not clear that this order authorizes Mueller to conduct any inquiry into any Comey concerned issues. Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, as the then acting Attorney General for matters Attorney General Jeff Sessions recused himself from, retained special counsel Robert Swan Mueller III to “conduct the investigation” purportedly “confirmed by then-FBI Director James B. Comey” concerning “any links and/or coordination between the Russian government and individuals associated with the campaign of President Donald Trump” and “any matters that arose or may arise directly from the investigation.” Comey’s testimony was that he felt Trump fired him for not telling the world what Comey knew and told Trump and others — that Trump was not under investigation. Comey’s only other testimony concerned post-election conduct of Mike Flynn communicating with the Russian ambassador, which the FBI already publicly cleared Flynn of wrongdoing. As such, neither would fit under the limited inquiry authorized by the special counsel order of Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein or the limited recusal of Attorney General Sessions, which shapes the limits of the special counsel authorization authority from Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein, and concerns “the campaign” and not post-election matters. Comey’s testimony, though, suggests otherwise, implying that Mueller has included any Comey-connected issues within his purview, despite the jurisdictional limitations of Mueller’s limited-by-law order authorizing his appointment, and the circumscribes terms of that order of appointment. Mueller’s unwillingness to recognize the limits of his authority raises precisely the concerns Professor Dershowitz and others have raised with the appointment of any special counsel in this matter. Independently, it gives rise to a greater concern in this context: the close personal friendship and public association between Mueller and Comey, which far exceeds any of the kind that led Attorney General Sessions to recuse from this inquiry in the first instance.

Additionally, concern over Comey reached new levels after Comey’s testimony, due to Comey’s dubious choice to drama-queen the main stage. (There is a reason lawyers tell their clients to keep their mouth shut.) Separate analysis — several by liberal-leaning Democratic law scholars and lawyers — identified four different grounds to potentially criminally prosecute and bring legal actions against Comey from his own words before the committee:

- Perjury for saying he had never memorialized any prior Presidential conversation, when evidence from a published book strongly suggests otherwise;

- Perjury for saying he had never received notice of the particular scope of Sessions’ recusal, when the Department of Justice’s own emails to Comey strongly suggests otherwise;

- Perjury for saying he only released details of his memos after President Trump tweeted about taped conversations, when a New York Times story from the day before the tweet strongly suggests otherwise;

- Violating various records and employment related laws in removing and leaking FBI memos to the New York Times, memos Comey cannot seem to now locate;

How can Mueller believe anyone will see his actions as impartial when it requires reviewing all matters of credibility concerning Comey, including possible criminal charge consequences for Comey, when Mueller has been identified as friends of a “unique” “deep” and “close” kind with Comey for more than “a decade”? As important, for the integrity of the legal proceedings, it is essential the public at large see Mueller’s actions as impartial. After all, that is the entire point of a special counsel appointment: a prosecutor above reproach, by action and public perception. Does anyone think Mueller’s actions henceforth will be seen that way? Especially, after Comey conceded publicly he orchestrated the leaks to get a special counsel appointed, and that special counsel turned out to be his deep, close, personal friend, Mueller?

Trump critics, ask yourself this question: Would you be ok with Trump’s counsel Michael Cohen as special counsel? How about any other long-time Trump friend and ally? Trump-critics cannot demand Sessions’ recusal on the one hand, and then ignore the more glaring conflict at the center of Mueller’s role in this now Comey-dominated matter. The best legal rule of all time is a simple one: “what is good for the goose is good for the gander.” So it should be here. Session recused; so must Mueller.

Robert Barnes is a California-based trial attorney whose practice focuses on Constitutional, criminal and civil rights law. You can follow him at @Barnes_Law.

[Screengrab via Georgetown University]

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.